Back to series

A Summons to Covenantal Discipleship

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

The Current “Discipleship Crisis”

Anyone who is listening to what many professing Christians are saying about their faith these days knows that we have a bit of a “discipleship crisis” on our hands. Though there are many dimensions to this crisis, it stems in large part from the frequent adoption of increasingly truncated versions of biblical Christianity. Anyone who is listening to what many professing Christians are saying about their faith these days knows that we have a bit of a “discipleship crisis” on our hands. Though there are many dimensions to this crisis, it stems in large part from the frequent adoption of increasingly truncated versions of biblical Christianity.

As recent studies have shown, a large percentage of American young people who claim to be Christians have embraced a form of Christian belief that falls far short of a vigorous expression of biblical discipleship. Dubbed “moralistic therapeutic Deism” (MTD), its contours reduce God to something of a “divine Butler” who remains aloof from his people until they summon him to address some felt need and who asks only that his people be “nice” to others. Even a superficial examination of Jesus’ actual teachings reveals how unbiblical this form of discipleship really is. But it is also clear that this state of affairs does not plague merely the younger generation of American Christians. Rather, the researchers who conducted this study have concluded that Christian young people have adopted this version of Christianity because their parents and churches have mentored them toward this perspective. Researcher Kenda Dean opines: The problem does not seem to be that churches are teaching their young people badly, but that they are doing an exceedingly good job of teaching youth what we really believe: namely, that Christianity is not a big deal, that God requires little, and the church is a helpful social institution filled with nice people focused primarily on “folks like us”… What if the blasé religiosity of most American teenagers is not the result of poor communication but the result of excellent communication of a watered-down gospel so devoid of God’s self-giving love in Jesus Christ, so immune to the sending love of the Holy Spirit that it might not be Christianity at all?… If this is the case… then perhaps most young people practice Moralistic Therapeutic Deism not because they reject Christianity, but because this is the only “Christianity” they know. Obviously, this narcissistic version of “Christian” discipleship requires very little from its adherents, resulting in lifestyles that are hardly “salty” enough to compel others to turn from their own narcissism so as to follow the Jesus of the Scriptures. In fact, this insipid religiosity has resulted in a pervasive disillusionment by the watching world regarding Christians and their claims. Rather than standing as beacons of integrity, justice, compassion, and purity, Christians are increasingly viewed by non-Christians with skepticism, indifference, and even cynicism. Since Christianity is always but one generation from extinction, this dilution of Christian discipleship and its impotent evangelistic influence should cause great concern for every thoughtful believer. What might be said in response to this state of affairs? Certainly, since MTD is patently unbiblical, if there is to be any resurgence in Christian vitality, the church must recover a profoundly biblical understanding of discipleship. That is to say, if these popular perversions of Christianity are to be corrected, it will only come through hearing Jesus’ own voice as it is meditated to us through the Scriptures. But in order to hear him faithfully, we must also recover a big-picture understanding of God’s purposes as they come to their fullest expression in Jesus. For our discipleship will reflect what Jesus had in mind only if we hear his voice and experience the power of his ministry in the robust richness of first-century Judaism. Only then should we feel any confidence that we have gotten things right as his disciples in the twenty-first century. In other words, if Christians are to expect people to take Christianity seriously in our context, then Christians must begin taking Jesus seriously in his context. This is what I have attempted to do in my recent publication, Following Jesus, the Servant King. To address the contemporary aberrations of Christian discipleship, I set out to answer three questions from the Scriptures. These are the “why,” the “what,” and the “how” questions:

It didn’t take me very long to realize that the answers to these questions must be pursued in the context of the covenantal framework of the Scriptures. In fact, the loss of the biblical category of “covenant” in the church is likely one of the main reasons for the present impoverishment of Christian discipleship. My book is therefore a summons to return to “covenantal discipleship.” First, the “why” question. The “Why” QuestionWhy should we be concerned to follow all of Jesus’ commands when we have been saved by grace? The “why” question emerges from the difficulty of sorting out the reason for an all-consuming concern for righteousness, while at the same time affirming the New Testament’s declaration that we are saved entirely by the grace of God in Jesus. It is Christ alone who fulfilled the righteous requirements of the law on our behalf (Rom. 8:3), and it is he alone who bore the curse of the law in our stead (Gal. 3:13). Being counted righteous before God, therefore, turns not on our own concerted attempts to live righteous lives, but rather on receiving this verdict through faith in Jesus (Rom. 3:28; Eph. 2:8–9). This is where the “why” question enters, encrusted with all sorts of related theological issues pertaining to grace and demand. Might we fall into a form of legalism if we actually strive to obey all of Jesus’ demands? Wouldn’t this transfer our confidence before God to ourselves and deny the sufficiency of Jesus’ finished work in the process? In fact, shouldn’t we rather view the extravagant demands of Jesus as persistent reminders of our inability to meet God’s standards, thereby nudging us back to his grace? Reducing the demands of Jesus to some realistic form of moralism might actually appear to be appropriate when viewed in this light. To answer the “why” question and its corollaries, we must realize that the interplay between grace and demand permeates the covenantal framework of the Old Testament. In fact, every biblical covenant is grounded in grace—whether that be creation grace, sustaining grace, redeeming grace, or the grace that comes through divine promises about the future. This means that those who enter into covenant with God do so in a gracious reality. In other words, legalism—the attempt to earn God’s favor through meritorious acts—is never in view in the biblical covenants, properly understood.

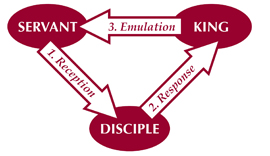

Israel’s deliverance from their Egyptian enslavement (Exod. 12:31–42) leads directly to Sinai and the righteous demands of the law (Exod. 20:1–17). We should therefore not be surprised when the same pattern confronts us in the New Covenant—a covenant instituted in the graciousness of Jesus’ atoning death and vicarious life of righteousness, but which leads to his self-denying, cross-bearing summons (e.g., Matt. 10:37–39; 16:24–26). Yet the answer to our “why” question is not simply found in observing the repetition of this covenantal pattern. The connections to our discipleship go far deeper than this. This is because both sides of the covenantal relationship find their fulfillments in Jesus. On the one hand, all of the gracious elements of the covenants lead directly to Jesus. For instance, Jesus is the true Seed of Abraham through whom the patriarch’s promises are mediated (Gal. 3:15–29). He himself is the Lamb who provides the climactic fulfillment of the Passover deliverance through his crucifixion and resurrection (Luke 22:19–20). And he is the greater Son of David who fulfills the expectation of an heir reigning on an eternal throne (Luke 1:30–35). In each case, Jesus brings God’s covenantal grace to its zenith. In these and other ways, Jesus mediates God’s covenantal grace, epitomized by his role as the great Servant of the Lord, who does for Israel (and the rest of us) what the people could not do for themselves. On the other hand, Jesus fulfills the law by articulating the end-time expression of God’s demand of righteousness. This is why he repeatedly places his commands in the neighborhood of discussions about the law (e.g., Matt. 5:17–48). Since he is the great Son of David, he fulfills the expectation of the righteous King, reigning over a transformed people and demanding from them the righteousness befitting members of the kingdom of God. In the end, we find our answer to the “why” question in the framework of the New Covenant. Those who have experienced through Christ the internalization of the law (Jer. 31:33), the indwelling of the transforming Spirit of God (Ezek. 36:26–27), and the once-for-all atonement in Jesus’ death (Jer. 31:34), will inevitably respond in obedience and fidelity to his righteous commands. Put otherwise, (1) having been graced by Jesus in his Servant work, (2) genuine disciples will respond faithfully to Jesus’ royal summons to righteousness. And since Jesus lived out the life of the Servant, (3) followers of the King will ultimately emulate the Servant. We might depict this conception of discipleship accordingly: |

|

The direction of the arrows is crucially important. The nature of the Servant’s work means that it cannot be emulated—at least initially. There is only one thing that can be done with grace. It must be received (Mark 10:45; 14:22–24). The direction of the arrows is crucially important. The nature of the Servant’s work means that it cannot be emulated—at least initially. There is only one thing that can be done with grace. It must be received (Mark 10:45; 14:22–24).

Thus discipleship appropriately begins in the reception of the Servant’s grace. But those who receive this grace are also covenantally compelled to respond to Jesus’ all-encompassing summons to righteousness and fidelity (Matt. 5:20; 16:24). Grace that is thoughtfully received never leaves the individual unchanged. The one who has been graced by the Servant will therefore be moved and empowered to follow the King in all of his discipleship demands. |

|

The “What” QuestionWhat is it that Jesus commands us to do as his disciples? As we know, people answer this question in a variety of ways. Some reduce it to “being nice” to others. Some view Jesus through Paul’s “gospel lens” and perceive only the necessity of faith in him as their gracious savior. Some engage in various social justice causes, seeking to obey Jesus’ great command to love their neighbors as themselves. Others translate Jesus’ commands into guidelines involving such things as not swearing, smoking, drinking, or having sex outside of marriage. Still others sell most everything and go to the ends of the earth with the gospel. But what does Jesus mean when he calls people to a life of discipleship? Once again, our answer comes in the covenantal framework that he fulfills. Since Jesus is the great King, who reigns over the New Covenant era, it is not surprising that he articulates the covenantal demand of righteousness, summoning people to follow him as one would follow God (Luke 18:18–23). For this reason, Jesus claims in Matthew 5:17 to be bringing the fulfillment of the law (and the prophets). Our knee-jerk reaction to this claim might be to interpret it as implying he would be the one to live out the law’s commands himself or to provide the final atoning sacrifice required by the law. But the nature of his fulfillment in this context turns out to be neither of these. Rather, as the succeeding verses make clear (vv. 21–48), his fulfillment consists in articulating the end-time expression of the law for his new covenant disciples.

And yet, even though Jesus affirms the eternality of each of the law’s provisions (Matt. 5:18), it is clear that some aspects of the law are covenantally altered as they pass through Jesus’ fulfillment. In reality, Jesus’ fulfillment does not always affect the law in the same way. Rather, each instance of Jesus’ interaction with the law must be studied in its own context. To capture the essence of the kinds of things that Jesus does with the law, we might use three metaphors, each of which pertains to light. Yet we will notice that even though each of these is distinct in itself, they all lead to the same general result—the high demand of righteousness in the new-covenant era. Jesus the “Filter”As the “filter,” Jesus’ fulfillment renders certain aspects of the law obsolete, as each of them is superseded by the realities to which they were pointing all along. Temple sacrifices are fulfilled, of course, in Jesus’ cross-work (Matt. 26:17–20; Hebrews 7–10). Circumcision in the flesh is eclipsed by the circumcision of the heart, performed by the Spirit (Rom. 2:25–28;Col. 2:11–12). The external function of the food laws is replaced by the internal witness of the Spirit regarding those things that defile the person (Mark 7:1–23; Gal.5:19–24). And Moses’ temporary concession to allow frequent divorces is largely rescinded by Jesus’ summons to lifelong marriages characteristic of the “one flesh” union (Mark 10:2–12). Although each of these results in the obsolescence of an aspect of the law, thereby changing its ongoing function, profound righteousness of word and deed is the consistent outcome. Jesus the “Lens”

Jesus the “Prism”As the “prism,” Jesus raises the demand of the law to a new level of righteousness. This heightened demand should not surprise us, since with Jesus the kingdom of God has come, replete with its empowering new-covenant blessings. Accordingly, Jesus raises the murder prohibition to the proscription of misplaced and unrepented anger (Matt. 5:21–26). He elevates the adultery prohibition to condemn even the lusting after another in one’s heart (Matt. 5:27–30). He also adjusts his followers’ use of the law, exhorting them to forgo personal rights instead of defending them (Matt. 5:38–42). And he stretches the love command to extend far beyond one’s neighbor to include within its purview everyone, even one’s enemies (Matt. 5:43–47). Each of these examples demonstrates that Jesus not only preserves the Old Testament concern for righteousness—he extends and even elevates it! Jesus’ Missional SummonsFinally, since Jesus brings the Old Testament covenants to their end-time fulfillments, his discipleship summons necessarily includes the call to mission. All the way back in the call of Abram, God announced his intention to bless all nations through him and his seed (Gen. 12:3). God also declared to the generation who received the Mosaic Covenant that they were “a kingdom of priests” (Exod. 19:6), suggesting their role of mediating the knowledge of Israel’s God to the nations of the world. Similarly, the Davidic Covenant envisions a day when the Davidic heir will inherit “the ends of the earth” (Ps. 2:8–12) and mediate the Abrahamic blessings to all nations (Ps. 72:1, 8, 17).

That is to say, as men and women from every nation bow their knees to Jesus in response to the kingdom mission of his disciples, the reign of the Davidic Son of Man is extended graciously among the nations until the day he returns in glory and great power (Matt. 28:18; Dan. 7:14; Ps. 2:8–9). When we compare the nature and scope of these discipleship commands with the popular revisions of Christianity in our day, it becomes quite obvious whose voice people are actually now hearing. And it certainly is not the voice of Jesus! But if we listen carefully to the Gospel writers, Jesus’ clarion summons can still be heard, beckoning us to a discipleship that permits us no wiggle room for compromise. It is at this point, then, that our third question raises its hoary head. Knowing our own inconsistency and fickleness of heart, how are we to do this? The “How” QuestionHow can we live out Jesus’ high demand of righteousness? In many ways, this brings us to the crux of the matter. As we have seen, anyone who is serious about studying Jesus’ commands realizes rather quickly that he calls us to a more bracing form of righteousness than merely being nice to others or avoiding various lifestyle vices. How, then, are we to follow him faithfully? Those who are honest with themselves while reading the Sermon on the Mount will readily admit their consistent failure to live up to Jesus’ standards. This is actually prophetically unexpected, given the prophets’ wildly optimistic descriptions of the righteousness lived out by the returned-from-exile, new-covenant people (e.g.,Isa. 60:3; 62:1–12; Jer. 50:4–5; Ezek. 36:26–27). However, the reason for the dissonance between these expectations of a radically transformed remnant and the persistent failure of Jesus’ followers is to be found in Jesus’ surprising teaching regarding the inaugurated coming of the kingdom. That is to say, rather than the much-anticipated, cataclysmic in-breaking of God’s reign, by which he would climactically heal and transform his people, Jesus affirms that the kingdom has come only in part. It is here, “advancing forcefully” (Matt. 11:12), yet susceptible of being missed (Matt.13:31–33). It is only inaugurated. The payoff of this for our understanding of discipleship is rather significant. Rather than being completely transformed in the consummated kingdom, disciples of Jesus today have merely experienced the inauguration of the kingdom’s transforming power. Though the Spirit has been poured forth in our hearts, we continue to be divided in our affections and struggle to keep in step with the Spirit (Gal. 5:17, 25). How then are disciples in this inaugurated state of transformation to live faithfully in relation to the King’s summons?

Ideally, they lived within the covenantal dynamic of the reception of prior grace that empowered them to respond to God’s demand of righteousness. This, then, supplies us with the answer to our third question. Since we who inhabit this era of the inaugurated kingdom are not yet fully transformed, we continue to need the same sort of grace that initially ushered us into our covenant relationship with God. And we need this daily. In other words, we need to learn how to allow God’s pursuing and sustaining power to renew us every day so as to incline our hearts to follow Jesus. We therefore must return repeatedly to the Servant to receive ongoing empowerment to follow the King. And it is in this context that we will experience the ministry of the Spirit, the vivifying presence of the kingdom era. Even while he waited in Babylon for God’s vindication after the exile, Ezekiel describes God’s empowering work in the people who live in the postexilic era—the era in which we live: “I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit in you; I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. And I will put my Spirit in you and move you to follow my decrees and be careful to keep my laws” (Ezek. 36:26–27; cf. Joel 2:28–29). It is this expectation that has found fulfillment in the new-covenant era, as Paul repeatedly affirms: “He has made us competent as ministers of a new covenant—not of the letter but of the Spirit; for the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life” (2 Cor. 3:6; see all of vv. 1–18; cf. also Rom. 7:6; 8:1–17, 26–27; Gal. 5:16–18,22–25; and many others). Life in this covenant is one that is to be lived in the power of the Spirit. That much is clear. But what exactly does this mean? It is here that I frequently find myself a bit flummoxed. How is it that the Spirit’s work is received, accommodated, or otherwise actualized? And how is the Spirit’s work connected to Jesus? Though Paul seems often to assume that his readers know the answers to these questions, Jesus gives us a bit more clarity in his upper-room comments about the Spirit. Significantly he affirms that the Spirit’s ministry will be all about Jesus! He will remind the disciples of what Jesus taught (John 14:26), he will testify to them about Jesus (15:26), and he will make the riches of Jesus known to his followers (16:15). Though the focus of the Spirit’s work in this context may be on the communication of propositional truth, Jesus’ riches are much more dynamic than merely his teachings, for Jesus not only taught—he acted! And it is in these actions that we find most clearly the grace of the new covenant.

So what is it that disciples need to remember and receive from Jesus so as to enable them to respond more faithfully each day to Jesus’ discipleship summons? Certainly the multifaceted ways in which Jesus fulfills the grace of the Old Testament covenants would be the general context in which to answer this question. But we can sharpen this even further by pondering the grace that comes to us through Jesus’ specific ministry actions, and then intentionally receiving that grace daily through the Spirit’s work in our hearts and minds. In this regard, we can speak of Jesus in his roles of Representative, Redeemer, Restorer, and reigning King. Jesus the RepresentativeAs the Representative, Jesus takes up the role of Israel (and even Adam) and, on their behalf, brings their failed history to its successful fulfillment. Set within the context of John the Baptist’s efforts to bring about the righteous remnant that was prepared for the separating judgment and transforming blessing of the one “coming after” him, John is understandably puzzled when Jesus comes to him for baptism. But Jesus’ reply (Matt. 3:15) implies that he viewed himself as the one who would bring about the very fulfillment of John’s ministry. That is, in his baptism, Jesus was identifying himself with the need of Israel and serving notice that he would bring about the long-awaited righteous remnant in himself—he was to be the remnant of one!—for it would be in his own life that the expectation of the righteous people of God would finally be realized. His successful reenactment of Israel’s testing's in the wilderness then demonstrates the truth of the divine identification of Jesus at his baptism—he truly is God’s Son and his Servant in whom the Lord takes great pleasure (Matt. 3:17; cf. Ps. 2:7; Isa. 42:1). This remarkable representative grace is now available to his followers, for in his righteousness we are now invited to stand (Rom. 5:2). Jesus the RedeemerSet within the historical context of Judah’s exile and return, Jesus the Redeemer brings to culminating fulfillment the role and experience of Isaiah’s Servant of the Lord (cf. Isa. 42:1–9; 49:1–13; 50:4–9; 52:13–53:12). Accordingly, Jesus’ crucifixion brings to consummation the role of the righteous remnant by absorbing in himself the covenantal curse (cf. Deut. 28:32, 36–37, 41, 64–68), accomplishing the final atoning sacrifice for God’s covenant people. Jesus’ cross is therefore appropriately to be understood as the culmination of the exile of God’s people. God’s acceptance of Jesus’ suffering is then climactically affirmed in Jesus’ resurrection, which itself should be perceived as the climax of the return of God’s people from exile. This is the grace of Jesus, the Redeemer. Not only has he successfully fulfilled the law’s demands for us, he has also borne the law’s curse on our behalf. As Paul exults, “Therefore, there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Rom. 8:1)! Jesus the RestorerAs the Restorer, Jesus brings to fulfillment multiple covenantal hopes pertaining to the restoration of the nation from their brokenness and unfaithfulness. Several ministry actions are in view here. For instance,when he calls twelve men to be his disciples, Jesus is serving notice that he is beginning the fulfillment of the long-anticipated return from exile by all of God’s people (e.g., Isa. 11:11–12). Our own call to discipleship participates in this same restoring grace, now broadening out to include all people. When Jesus sits down at the table with the wrong sort of people, he is acting out a living parable of God’s pursuing grace toward those who cannot purify themselves. Rather than contracting the defilement of those around him, Jesus inserts himself into their midst as the embodiment of God’s mercy that cleanses the impure. Jesus’ table invitation remains open also to us every day, even in our recurring defilement. When Jesus heals the sick and handicapped, he is demonstrating his role of bringing to an end the covenantal unfaithfulness of God’s people. That is to say, when Jesus heals the sick and restores wholeness to the handicapped, he is inviting others to perceive in his gracious actions much more than simply miraculous power! Rather, he is demonstrating that it is he who will bring about a healed and transformed people, faithful to the God of the covenant. Once again, prior grace elicits and empowers covenantal faithfulness. This healing grace, which encompasses both physical and spiritual elements, is perpetually on offer to Jesus’ disciples today. Finally, when Jesus exorcises demons from people, he is signaling the arrival of the era when Satan’s damnable work accomplished in Eden is coming to an end. Jesus’ exorcisms therefore should be interpreted within this framework, serving notice that God is already now attacking the dominion of darkness (Matt. 12:28–29), and foreshadowing the day when Satan and his forces will finally be condemned (Matt. 25:41; 13:39–43). The authority that Eve and Adam surrendered to Satan is therefore being reclaimed in Jesus’ powerful ministry, offering gracious refuge and hope to us, who continue to live in the age where Beelzebub’s destructive influence is still afoot. Graciously, Jesus has bequeathed to us this authority to continue this ministry of setting people free from spiritual bondage. Jesus the Reigning KingAs the reigning King, Jesus fulfills the pattern of the suffering and vindicated Davidic king. Arising from the agony inflicted upon him, the crucified Jesus voices his cry of despair in the words of the psalmist, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matt. 27:46; cf. Ps. 22:1). In so doing, Jesus invites those watching to locate his fate within the framework of David’s own experience of divine abandonment, in spite of the covenantal promises to the contrary (2 Sam. 7:8–16; cf. Psalm 89). The covenantal dissonance that David experienced therefore finds tragic repetition in Jesus’ life. Will God prove faithful to his covenant promises in spite of cruciform evidence to the contrary? It is in this context that the resurrection of Jesus represents more than merely Jesus’ conquest over death. Rather, Jesus’ resurrection brings to culmination this unexpected kingly pattern, as he is vindicated from the ignominy of the cross and exalted to the highest throne (Ps. 110:1; Acts 2:34). Accordingly, David’s expectations of universal ramifications stemming from his vindication (Ps. 22:27–31) are climactically fulfilled in Jesus, confirming that Jesus is the one who will indeed reign forever (Luke 1:32–33; 2 Sam. 7:13, 16), wielding all authority in heaven and earth (Matt. 28:18; Dan. 7:14; Ps. 2:8). Once again, God’s covenant grace comes to us through Jesus, as we perceive Yahweh’s faithful fulfillment of the promises he made to David. Our King has been vindicated and now sits enthroned forever! As we who are his disciples respond to this grace by proclaiming and demonstrating its reality around the world, his reign is extended further and further, anticipating its great consummation in the kingdom to come. In each of these ways, God extends his prior, covenantal grace to us through his Son. When we live covenantally, pondering each of these ministry actions and receiving their gracious message, the Spirit takes of Jesus’ riches and makes them present with us and in us, empowering us to follow him in the all-encompassing call of discipleship. This grace enablement is the answer to the “how” question. Concluding ThoughtsIn the end, the answers to our three discipleship questions have obliterated the graceless and costless nature of so many contemporary depictions of Christian discipleship. On both sides of the covenantal framework, these modern mutations of Christianity dramatically fail to capture and preserve what Jesus has in mind when he calls people to follow him. What does this suggest to us? Among the many things that could be said, it certainly should imply to us the necessity of rethinking our evangelistic methods. Could it be that we have so overemphasized salvation by grace alone through faith that we have failed to communicate the demand side of the covenant? Jesus is not only the Servant, who lavishes his grace on us—he is also the reigning King, who demands wholehearted loyalty and devotion. If we continue in failing to communicate what it means to enter into covenant with God at the front end of people’s Christian experience, they likely will adopt a faulty expression of discipleship that may be worse than having no Christian commitment at all. Along with helping people to fall in love with their Savior, we must teach them to fall at the feet of their King. This must also be true of us who seek to lead others into this understanding of discipleship.

What does it mean that Christians are those in whose hearts and minds the law has been internalized? What are the implications of Jesus’ reign over them as the righteous Davidic King? How is life to be lived so as to participate in the mediation of the Abrahamic blessings to the nations? In other words, modern-day Christians need to learn to live their lives within the ongoing narrative of God’s covenantal purposes. Otherwise we will almost certainly define our discipleship in ways that fall woefully short of the biblical vision. Finally, we must come to grips with the inaugurated nature of the kingdom in the present era, inferring from this our recurring need for God’s vivifying and renewing grace. Learning to live life within the covenantal dynamic of grace and demand is the key to enduring faithfulness to Jesus. That is to say, we must learn not only to be saved by grace, but also how to live in grace. In so doing, we will discover the enablement that grace offers us, inclining our hearts and galvanizing our wills to respond to Jesus’ call on our lives. And the result of this will be increasingly consistent lives of discipleship, through which God will mediate his great covenantal blessings to others, compelling them also to follow Jesus, the Servant King. May God grant us grace to this covenantal end. |

|

Jonathan M. Lunde

ProfessorJonathan M. Lunde, is professor of New Testament at Talbot School of Theology. He earned his MDiv at Lutheran Brethren Seminary, and ThM and PhD at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Prior to coming to Talbot, he taught for seven years at Trinity College in Deerfield, Illinois, and also has local church ministry experience. He is the author of Following Jesus, the Servant King: A Biblical Theology of Covenantal Discipleship. He has also authored various articles and book chapters.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

A Welcome Change in Apologetics

by Randy Newman, Aimee Riegert on April 19, 2024We’re burdened for our friends who don’t know...Read More

-

Questions That Matter Podcast – Samuel James and Digital Liturgies

by Samuel James, Randy Newman on April 19, 2024

-

The Side B Stories – Dr. James Tour’s story

by Jana Harmon, James Tour on April 12, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Isn’t Morality Relative?

by Christopher L. Reese on April 1, 2024It is widely accepted in the Western world...Read More

-

Do Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God?

by Andy Bannister on March 1, 2024

-

Artificial Intelligence and Its Impacts on Humanity

by John Lennox on February 13, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

20599

GLOBAL EVENT: 2024 Study Tour of C.S. Lewis’s Belfast & Oxford

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=global-event-2023-study-tour-of-c-s-lewis-belfast-oxford-2&event_date=2024-06-22®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-06-22

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

GLOBAL EVENT: 2024 Study Tour of C.S. Lewis’s Belfast & Oxford

On June 22, 2024 at 12:00 pmat Belfast, Northern Ireland & Oxford, EnglandSpeakers

Jonathan M. Lunde

Professor

Team Members

Jonathan M. Lunde

ProfessorJonathan M. Lunde, is professor of New Testament at Talbot School of Theology. He earned his MDiv at Lutheran Brethren Seminary, and ThM and PhD at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Prior to coming to Talbot, he taught for seven years at Trinity College in Deerfield, Illinois, and also has local church ministry experience. He is the author of Following Jesus, the Servant King: A Biblical Theology of Covenantal Discipleship. He has also authored various articles and book chapters.

And yet this gracious foundation never diminishes the divine demand of righteousness. Noah’s deliverance from the flood and the divine promise to maintain the seasonal cycles (Gen. 9:9–16) ground God’s requirement to steward the earth and respect its life (Gen. 9:4–7). Abraham’s reception of the divine promises of incomprehensible blessings (Gen. 12:1–3, 7; 15:5–21) results in God’s command that the patriarch walk faithfully before him (Gen. 17:1–14).

And yet this gracious foundation never diminishes the divine demand of righteousness. Noah’s deliverance from the flood and the divine promise to maintain the seasonal cycles (Gen. 9:9–16) ground God’s requirement to steward the earth and respect its life (Gen. 9:4–7). Abraham’s reception of the divine promises of incomprehensible blessings (Gen. 12:1–3, 7; 15:5–21) results in God’s command that the patriarch walk faithfully before him (Gen. 17:1–14). This finds agreement with Jeremiah’s great description of the “new” covenant that God will one day make with his people (Jer. 31:31). Rather than dispensing with the law (as many Christians think), the new covenant involves the internalization of the law in his covenant people (v. 33). Jesus’ end-time articulation of the law is therefore what is to be internalized in the hearts and minds of his followers.

This finds agreement with Jeremiah’s great description of the “new” covenant that God will one day make with his people (Jer. 31:31). Rather than dispensing with the law (as many Christians think), the new covenant involves the internalization of the law in his covenant people (v. 33). Jesus’ end-time articulation of the law is therefore what is to be internalized in the hearts and minds of his followers. As the “lens,” Jesus brings back into focus an element of the law that had become obscured by the traditions of the elders and teachers of the law. In this role, Jesus does not do anything to the law itself. But he does invalidate contemporary interpretations that have gone awry, inhibiting the living out of true righteousness. Here Jesus recovers the demand to show mercy toward sinners by pursuing them into their contexts (Matt. 9:9–13) and commanding that his followers sacrificially care for the needy they encounter (Luke 10:25–37). Jesus also recovers the demand that God’s people serve as the conduit of Sabbath blessings to those otherwise destitute and in need of rest (Luke13:10–17). Similarly, he restores the demand to speak the truth in every situation (Matt. 5:33–37). In each case, Jesus restores the original intention of the law, rebuking and discarding those interpretations that paradoxically were giving rise to less than what the law was intending.

As the “lens,” Jesus brings back into focus an element of the law that had become obscured by the traditions of the elders and teachers of the law. In this role, Jesus does not do anything to the law itself. But he does invalidate contemporary interpretations that have gone awry, inhibiting the living out of true righteousness. Here Jesus recovers the demand to show mercy toward sinners by pursuing them into their contexts (Matt. 9:9–13) and commanding that his followers sacrificially care for the needy they encounter (Luke 10:25–37). Jesus also recovers the demand that God’s people serve as the conduit of Sabbath blessings to those otherwise destitute and in need of rest (Luke13:10–17). Similarly, he restores the demand to speak the truth in every situation (Matt. 5:33–37). In each case, Jesus restores the original intention of the law, rebuking and discarding those interpretations that paradoxically were giving rise to less than what the law was intending. It is for this reason that Jesus declares his followers to be the “salt of the earth” and the “light of the world” (Matt. 5:13–16), for they are the means through whom this covenantal expectation would find its fulfillment. Jesus’ sending out of his disciples on their missionary journeys (Matthew 10; Luke 10) and his so-called “Great Commission” (Matt. 28:19–20) express this covenantal purpose. Consequently, as his disciples proclaim and demonstrate the presence of the kingdom of God (Matt. 10:1, 5–42), often exposing themselves to persecution and impoverishment in the process (Matt. 25:31–46), these great covenantal hopes will be realized.

It is for this reason that Jesus declares his followers to be the “salt of the earth” and the “light of the world” (Matt. 5:13–16), for they are the means through whom this covenantal expectation would find its fulfillment. Jesus’ sending out of his disciples on their missionary journeys (Matthew 10; Luke 10) and his so-called “Great Commission” (Matt. 28:19–20) express this covenantal purpose. Consequently, as his disciples proclaim and demonstrate the presence of the kingdom of God (Matt. 10:1, 5–42), often exposing themselves to persecution and impoverishment in the process (Matt. 25:31–46), these great covenantal hopes will be realized. The answer once again comes to us from the covenantal framework of the Old Testament. It is obvious that within the economy of the Mosaic Covenant, the Jews were to live in a recurring pattern of remembrance, reception, and response. Throughout their calendar year, regular festivals, celebrations, and Sabbaths jogged their collective and individual memory to reflect on and receive afresh the grace of God to them as a people. Only then were they to respond to God’s call to righteousness. For example: “Remember that you were slaves in Egypt and that the LORD your God brought you out of there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Therefore the LORD your God has commanded you to observe the Sabbath day” (Deut. 5:15; cf. Deut. 15:11–15; 16:2–3;16:12; 24:17–22; Josh. 1:13; 23:3–11; and many others).

The answer once again comes to us from the covenantal framework of the Old Testament. It is obvious that within the economy of the Mosaic Covenant, the Jews were to live in a recurring pattern of remembrance, reception, and response. Throughout their calendar year, regular festivals, celebrations, and Sabbaths jogged their collective and individual memory to reflect on and receive afresh the grace of God to them as a people. Only then were they to respond to God’s call to righteousness. For example: “Remember that you were slaves in Egypt and that the LORD your God brought you out of there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Therefore the LORD your God has commanded you to observe the Sabbath day” (Deut. 5:15; cf. Deut. 15:11–15; 16:2–3;16:12; 24:17–22; Josh. 1:13; 23:3–11; and many others). Inserting these insights into our discipleship diagram, it is clear that a new arrow must be added—one that captures the frequent return to the Servant Jesus for the grace needed to continue following him as King. And all through this, the Spirit makes present the empowering riches of Jesus!

Inserting these insights into our discipleship diagram, it is clear that a new arrow must be added—one that captures the frequent return to the Servant Jesus for the grace needed to continue following him as King. And all through this, the Spirit makes present the empowering riches of Jesus! Second, our discussion should reveal to us the need for moving people into a deeper understanding of discipleship that includes a fuller grasp of the broader biblical narrative. Until the youth and adults in our churches are able to articulate their faith, rooting it in what God has been doing throughout history, we are in danger of leaving them to define their discipleship on their own terms, for their own purposes. We must, therefore, recover what it means not only to be a “Christian,” but also what it means to be a new-covenant follower of Jesus.

Second, our discussion should reveal to us the need for moving people into a deeper understanding of discipleship that includes a fuller grasp of the broader biblical narrative. Until the youth and adults in our churches are able to articulate their faith, rooting it in what God has been doing throughout history, we are in danger of leaving them to define their discipleship on their own terms, for their own purposes. We must, therefore, recover what it means not only to be a “Christian,” but also what it means to be a new-covenant follower of Jesus.