Back to series

Recommended Reading:

The Great Reformer (Part 2)

The second of two articles dealing with the life and significance of the British evangelical social reformer, the seventh earl of Shaftesbury.

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

Shaftesbury remarked toward the end of his life that “I know what constituted an Evangelical in former times. I have no clear notions what it constitutes now.”1

He was a long-standing friend, confidant and supporter of the great Baptist preacher, Charles Haddon Spurgeon. Shaftesbury described Spurgeon as “a wonderful man, full of zeal, affection, faith, abounding in reputation and authority, and yet perfectly humble.”2

Spurgeon, in turn, bemoaned to Shaftesbury, “men in whom I had confidence are turning aside.”3 A year before Shaftesbury died he was asked by Spurgeon to preside over the celebrations for the latter’s fiftieth birthday. Spurgeon pressed Shaftesbury, “you shall be allowed to go in one hour if you feel at all tired…I should like you to come because I want old-fashioned Evangelical Doctrine to be identified with the event.”4

Shaftesbury’s identity as and understanding of what it means to be Evangelical is crucial to understanding his motivations. In this second article we turn to Shaftesbury’s beliefs and how they formed and shaped his life and activities. In doing so we will discover passion and insight, a clarity of judgment that is at times uncomfortable, but above all a man of God dedicated to the service of the Savior. We will consider his theology, his battle on behalf of the “climbing boys,” and finally an assessment of his place in history.

Shaftesbury’s theological motivations

Shaftesbury’s application of classic Evangelical and Protestant doctrine was powerful and dynamic. In the context of the advancement of Enlightenment rationality, the power of the state and even the secular narrative, Shaftesbury stood firm. Christian theology was to be applied to society, not submerged beneath it.

Evangelical belief, according to Shaftesbury, provided a template for the life of discipleship. His theological motives could be summarised in three strands; first, the principle of the Bible and its teaching; second, the voluntary worker principle expressed across denominational boundaries; third, the implications of the end times.

Shaftesbury’s starting point with the Bible could not have been clearer. He told the annual meeting of the Church Pastoral Aid Society in 1862:

There is no security whatever except in standing upon the faith of our fathers, and saying with them that the blessed old Book is ‘God’s Word written,’ from the very first syllable down to the very last, and from the last back to the first.5

Scripture was to be studied privately and devotionally, guiding the whole of life and being equally applicable in both private and public domains. He argued that Second Chronicles should be studied, prayed over and weighed by every person in public life. The Bible was its own missionary, accessible to the ordinary person. He told the Bible Society in 1860:

Tens of thousands have thrown off their corrupt and ignorant faith, not in consequence of the efforts of preachers, or teachers, or lecturers, but simply and solely from reading the Word of God, pure and unadulterated, without note or comment, without any teaching except the blessed teaching of God’s Holy Spirit.6

Shaftesbury’s commitment to both inter-denominational unity and the voluntary worker principal (the use of lay people – lay agents – in the Lord’s work) combined powerfully in his twin concerns of evangelism and social action. He described the Bible Society as “a solemn league and covenant of all those who ‘love the Lord Jesus Christ with sincerity’; that it shows how members of the Church of England and Nonconformists may band together in one great effort.”7

The voluntary Christian society was the great place where all Christians could come together for service. He saw this particularly with his work with the City Mission and with Ragged Schools. He told the Ragged School Union, “all who care for the advancement of Christ’s kingdom, to whatever church they belong, must join together, heart and soul, for the purpose of bringing to completion this great, this mighty undertaking.”8

Shaftesbury was driven by the Christian vision of the unfinished task, of bringing the gospel to the unevangelized, especially the poor and marginalized, and its transforming power to bear upon a society that claimed to be Christian.

Shaftesbury was driven by the Christian vision of the unfinished task, of bringing the gospel to the unevangelized, especially the poor and marginalized, and its transforming power to bear upon a society that claimed to be Christian.

He had an acute sense of the Lord’s calling of all his people. Evangelization and transformation should not be left just to the clergy. The lay agency principle was a much more effective way of the gospel penetrating even into the darkest depths of London’s slums. Shaftesbury was scathing about the Victorian passion for building churches – “we want men, not churches.”9

The lay workers employed in the voluntary societies were key to his vision. Some, such as the City Missionaries were paid, others, many of them women, were the volunteer teachers in the ragged schools, Scripture Readers and parish visitors.

Indeed his view was that these workers were in by far the best position to assess social need. The advance of the state rather led to the collapse of the volunteer principle as so many social functions were taken over by government.

The third, and crucially important, area of Shaftesbury’s theological concern was in the area of eschatology. It is here that we see a real dynamic, investing a traditional Evangelical theological position with transformative power. Too much ink was spilt in the nineteenth century, as now, over the minute details of various eschatological schemes. Shaftesbury’s commitment began with an assertion of the priority of the Second Advent, which he described as “the hope for all the ends of the earth.”10 He was, however, also clear where the boundaries lay:

…the Second Advent of our Blessed Lord. Pay no attention to excited and angry critics, who charge such a scheme with all the extravagancies of the fifth monarchy, and the millennial inventions. The Second Advent, as an all-sufficient remedy, should be prayed for; and as a promise, should be looked for. The mode, form, and manner of that event are not revealed, and therefore no business of ours.11

A salutary reminder. This position was fundamental to Shaftesbury’s theology and his ability to develop a vision for evangelism and social action. It enabled him to have a clear vision of the unity of body and soul—for they would be united again at the end. It turned on its head Evangelical obsessions with chronology and timing and replaced them with a call to discipleship.

The fascination with the minute details of the millennium proved to be an enormous distraction from the task at hand. Shaftesbury was a premillennialist. He believed that human sin was such that the condition of the world would worsen and only the Second Advent could offer ultimate hope. However, he reversed the classic premillennialist approach to life and to society.

Rather than wait for the ultimate reversal to happen with a life of quietism and pietistic withdrawal from society, Shaftesbury pressed the responsibility of the Christian to act.

He was not distracted by the mania for matching the signs of the times to the chronology of the book of Revelation or the setting of dates for the return of Christ. Hence, Shaftesbury was able to press very precisely the view that the day of judgement would include a reckoning for the believer’s stewardship of the gifts of God.

He urged constant attention to the responsibilities of the present and the dynamic of living in constant, yet unknown, expectation of the second coming. The duties of the Christian extended to the responsibilities of the nation, as all would be held to account. The nearness of the Second Advent and judgment was to Shaftesbury an impulse to action, not withdrawal.

Faithful and obedient discipleship in the period before the return of Christ lay at the root of his work. It was this which animated his labour as legislator, missionary activist, and supporter of Christian voluntary societies. He set it out clearly:

I am now looking, not to the great end, but to the interval. I know, my friends, how great and glorious that end will be; but while I find so many persons looking to no end, and others rejoicing in that great end, and thinking nothing about the interval, I confess that my own sympathies and fears dwell much with what must take place before that great consummation.’12

Climbing boys

Shaftesbury was a great campaigner against social evils. The “boy sweeps” was a matter which concerned him throughout his life and which he fought with tenacity. The wealthier members of society demanded that their chimney flues (the narrow funnel through which smoke rose until ejected into the atmosphere) be cleaned.

So did the insurance companies, nervous of the risk of fire. For much of the nineteenth century this was a process which was not yet mechanised. Hence the only way to effectively ensure that the sweep’s brushes could be fully extended up the chimney and the flue cleaned was to use manual labour. Since the flues were narrow, the younger the better.

Children as young as five were sold into the employment of the master sweeps by unscrupulous parents who gave the necessary assurances on age (from 1788 there was a minimum age of eight years old, but it was widely flouted).

Their existence was miserable. The incentives which were provided to encourage reluctant youngsters to climb the chimneys were cruel. They included forcing pins into feet of a boy or lighting a fire in the hearth. Deformities, injuries and deaths resulted. Once a boy was too big he was discarded onto the street.

Wilberforce had been an early campaigner but regulation was patchy. In 1840 Shaftesbury introduced a bill to prevent the employment of children as sweeps.

He noted in his speech that the practice had ‘led to more misery and degradation than prevailed in any other Christian country.’13 Once again we see the powerful link of the responsibilities of a Christian nation in response to the prevalence of sin in its midst. Shaftesbury was clearly in possession of first-hand information, probably from the City Missionaries, and was even involved in one successful ‘buy-out’ of a young sweep.

The 1840 legislation proved similarly ineffective as its predecessors. Then, in 1847, a master sweep was convicted of the manslaughter of a seven-year old boy. He had been forced into the flue of a chemical works just nineteen inches wide. He had inhaled the soot, suffered burns, was beaten and then died. Shaftesbury became chairman of the Climbing Boys Society.

The master sweeps were prevented now by the legislation from taking apprentices under the age of sixteen years. In 1853 Shaftesbury explained to the House of Lords that the provisions were circumvented by sweeps employing children to carry the bag of tools and brushes.

The master sweeps were prevented now by the legislation from taking apprentices under the age of sixteen years. In 1853 Shaftesbury explained to the House of Lords that the provisions were circumvented by sweeps employing children to carry the bag of tools and brushes.

Once inside, the doors would be locked and the child forced up the chimney. By this time more mechanisation was occurring in London, but not in the provincial cities. The government prevaricated. In 1863 a further report noted that the use of climbing boys was again on the rise and the illicit trade was returning to London.

There were still several thousand boys employed, as young as six, with the regulations continuing to be violated. The report noted the deaths of twenty three boys since 1840.

Shaftesbury introduced further legislation laying the blame at the door of the householders who resisted mechanisation. The rich, he added, prefer not to ask how their chimneys are cleaned.

Effective regulation continued to prove elusive. The fifth report of the Children’s Employment Commission in 1866 provided evidence of the continued evasion of the Acts introduced by Shaftesbury.

The Earl was stirred into action again in 1872 after eight year-old Christopher Drummond died in a flue. He tried to rouse public opinion with a letter to The Times, describing the practice as a disgrace to England.

Three years later a boy died in a chimney in Cambridge. This time The Times thundered into action in an editorial demanding final and resolute action. Shaftesbury moved in the Lords for an inquiry which was denied and so on 20th April 1875 he gave notice of new legislation. In his speech to Parliament, Shaftesbury said his interest lay in the temporal and eternal welfare of this oppressed group. He described the practices as Satanic.14

The Bill passed unscathed and effectively ended a century of misery. The Earl was seventy-four years old when the Act passed. He had shown remarkable tenacity and perseverance in the cause. This was a characteristic of his campaigns and a reason for his success. Meticulous in gathering and presenting evidence, for Shaftesbury both the eternal destiny and the bodily welfare of the child sweep were of equal concern.

Place in history

How are we to assess Shaftesbury’s life, significance and contribution to history? He resisted senior government office because it would threaten his independence. In 1866 alone he was offered a seat in the Cabinet three times by both Whig and Tory Prime Ministers.

As a result the legacy is probably greater, but perhaps less well known. His sense of calling and Christian passion and compassion ran very deep indeed.

Shaftesbury had a vision for God in society. This came from his uncompromising Protestantism, a conclusion that some might find uncomfortable. As a campaigner for some “party” causes he was unyielding. (For a discussion of Shaftesbury’s Protestant campaigning, see Tumball, Shaftesbury.) Undoubtedly he made errors and misjudgments. However, this same commitment gave him a clear vision for God in the public domain. It was because the nation was Christian that the state carried responsibilities for God’s creatures.

The role of the state was, however, limited. Shaftesbury looked for a partnership between a Christian state and the Christian voluntary society. This enabled him to create a unique Evangelical vision for mission. He saw the Evangelical voluntary societies as instruments used by God, practical expressions of Christian discipleship in preparation for the Second Advent and the day of judgement.

The return of Christ was an impulse to action. The advance of state intervention after around 1870 caused a serious imbalance in the relationship of the state and the voluntary sector and the Evangelical societies lost ground.

Shaftesbury inspired and exacerbated in equal measure. To him the campaigns for Protestant truth, evangelism and social reform were all driven by his Christian faith and Evangelical commitment. He achieved more than any government could ever have done. He was an intelligent and skilful operator.

As well as his reforms and Christian work in the nation, for ten years as Viscount Palmerston’s adviser he ensured more faithful appointments to the bench of Bishops. He studiously maintained his independence from government – the only offices he sought were the chairs of the Evangelical societies.

He was, in essence, a man, flawed, but also one of courage, integrity, consistency and persistence; in short, he was a man of passion. He showed to the nation true Christian leadership, discipleship and service. His legacy is on the statute books, in the voluntary evangelical mission societies and their work, evangelistic and social, and in the vision for a Christian nation and public policy. He was an inspiration for Christians in the public square then and now. Lord Shaftesbury, thank you.

Notes:

1. E. Hodder, The Life and Work of the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, Cassell & Co., London, Vol 3, 451

2. Shaftesbury, Diaries, 12th June 1875, Richard Turnbull, Shaftesbury: The Great Reformer, Lion Hudson, Oxford, 2010, p199

3. Ibid, 199

4. Ibid, 200

5. Ibid, 213

6. Ibid, 214

7. Ibid, 215

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid,

217

10. Lord Ashley, Diaries, 26th December 1847, Turnbull, Shaftesbury, 219

11. Turnbull, Shaftesbury, 220

12. Ibid, 222-223

13. Lord Ashley, House of Commons, 14th April 1840, Turnbull, Shaftesbury, 113

14. Ibid, 198

Richard Turnbull

Pastor Richard Turnbull is the director of the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics and a trustee of the Christian Institute. Richard also holds a first class honors degree in Theology and Ph.D. in Theology from the University of Durham. He was ordained into the ministry of the Church of England in 1994. Richard served in the pastoral ministry for over 10 years. He was also for 7 years the Principal of Wycliffe Hall, Oxford. He has authored several books, is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a visiting Professor at St Mary’s University, Twickenham.

Recommended Reading:

Richard Turnbull, Reviving the Heart: The Story of the 18th Century Revival (Lion Hudson, 2012)

The English Revival of the 18th century was an exciting time for Christianity that most people today know little about. For instance: What caused it and why did it spread? Did it prevent a revolution in the UK, similar to that which had convulsed France? And what effect did it have—locally, nationally, and globally? This book answers all of those questions and more.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

Making Sense of Science and Faith – Sharon’s Story

by Sharon Dirckx, Jana Harmon on September 13, 2024Dr. Sharon Dirckx was raised in a secular...Read More

-

Dismantling Atheism – Daniel’s Story

by Jana Harmon, Daniel on August 30, 2024

-

How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism

by Joseph Loconte, Aimee Riegert on August 23, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Isn ’t Atheism Based on Scientific Fact Whereas Christianity is Based on “Faith”?

by Cameron McAllister on September 1, 2024I once led a dialogue at the University...Read More

-

A Christian Response to Anti-Semitism

by Darrell Bock, Randy Newman, Thomas A. Tarrants on August 15, 2024

-

What Scientific Proof Do We Have That There Is a God?

by Christopher L. Reese on August 1, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

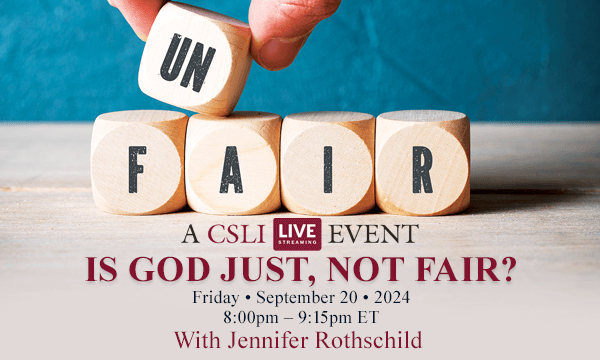

22667

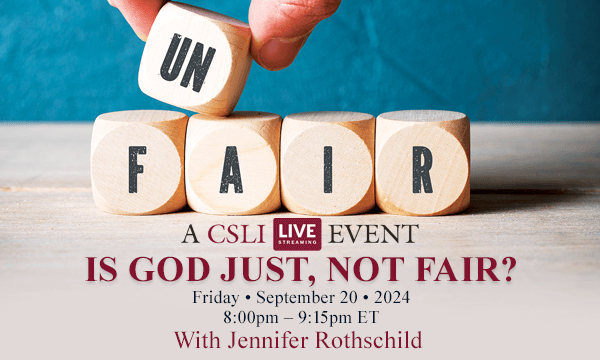

GLOBAL EVENT: Is God Just, Not Fair? with Jennifer Rothschild, 8:00PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=global-event-is-god-just-not-fair-with-jennifer-rothschild-800pm-et&event_date=2024-09-20®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-09-20

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

GLOBAL EVENT: Is God Just, Not Fair? with Jennifer Rothschild, 8:00PM ET

On September 20, 2024 at 8:00 pmSpeakers

Richard Turnbull

Pastor

Team Members

Richard Turnbull

PastorRichard Turnbull is the director of the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics and a trustee of the Christian Institute. Richard also holds a first class honors degree in Theology and Ph.D. in Theology from the University of Durham. He was ordained into the ministry of the Church of England in 1994. Richard served in the pastoral ministry for over 10 years. He was also for 7 years the Principal of Wycliffe Hall, Oxford. He has authored several books, is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a visiting Professor at St Mary’s University, Twickenham.