Back to series

"The Morning Star Of The Reformation"

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

"To Wycliffe we owe more than to any one person . . . our English language, our English Bible, and our reformed religion.”2

Who was this man to whom we owe so much?

John Wycliffe was born into a wealthy family in Yorkshire, England, circa 1330. At age fifteen he went to Oxford, by then the greatest university in Europe. A few years later, the Black Death killed a third of the population of England, including Thomas Bradwardine, the archbishop of Canterbury.

Bradwardine’s book On the Cause of God against the Pelagians, a bold recovery of the Pauline-Augustine doctrine of grace, would greatly shape young Wycliffe’s theology. Wycliffe completed his studies at Oxford, fulfilling his doctoral requirement by giving a series of lectures commenting on the whole Bible! As a teacher he soon became Oxford’s leading philosopher and theologian.

Wycliffe first made his mark as a philosopher, writing in Latin many treatises opposing the spiritual sterility of the skepticism of his day.

Advocate of Church Reform

Wycliffe began the second phase of his life when he became an advocate of church reform and entered the service of the king. Somewhat like Erasmus more than a century later, he attacked the abuses of the church, from the priests to the pope. He insisted that Christ gave the church authority over the spiritual, but not the temporal, realm. He traced the corruption of the church to the time of Constantine, when the emperor was thought to have endowed the papacy with temporal possessions and thus “poured poison into the Church.”3 Wycliffe criticized priests who were

Wycliffe began the second phase of his life when he became an advocate of church reform and entered the service of the king. Somewhat like Erasmus more than a century later, he attacked the abuses of the church, from the priests to the pope. He insisted that Christ gave the church authority over the spiritual, but not the temporal, realm. He traced the corruption of the church to the time of Constantine, when the emperor was thought to have endowed the papacy with temporal possessions and thus “poured poison into the Church.”3 Wycliffe criticized priests who were

. . . so occupied in heart about worldly lordships, and with pleas of business, that no habit of praying, of thoughtfulness on heavenly things, or the sins of their own heart or those of other men, may be kept among them: neither may they be found studying and preaching the gospel, nor visiting and comforting the poor.4

He insisted that the clergy should be stripped of all material, worldly privileges, to restore them to their proper spiritual life and work.

Wycliffe’s help was gladly embraced by the state in its ongoing battle with the church over issues of status, power, and control. In the eyes of the popes of his time, Wycliffe stood for England against Rome and for the state against the church. The Catholic Church was unable to control or silence Wycliffe, because he had powerful supporters in the state, and the church itself was experiencing a time of great internal dissension.

The so-called Babylonian Captivity (the relocation of the papacy to Avignon in 1309) was followed by the Great Schism (the division of Western Christendom in 1378 by the creation of two popes, one in Rome and one in Avignon). John Wycliffe saw this as a hopeful sign, saying that Christ “hath begun already to help us graciously, in that he hath cloven the head of Antichrist, and made the two parts fight against each other.”5

Wycliffe lost much of his secular support, notably the protection of John of Gaunt, son of Edward III, who for years had protected him from the wrath of the church. When this nobleman lost his power, and the weakness of the church gave the state greater confidence in its ability to prevail, Wycliffe was no longer needed. It was not the first time, nor would it be the last, that a Christian leader discovers that “it is better to take refuge in the Lord than to trust in princes” (Ps. 118:9 NIV).

Although Wycliffe now lacked political clout, the people still supported him. “If he is the weakest in power,” they said, “he is the strongest in truth.”6 In 1382 Wycliffe’s teaching was condemned by a council meeting in London. When the city was shaken by an earthquake, the Catholic officials interpreted it as a sign of God’s approval of their action. Others said, “If Wycliffe has been condemned by the bishops, then they have certainly been condemned by God.”7

Wycliffe, the Theologian

When in 1381 John Wycliffe was banished from Oxford, a place he called his greatest love, he took up residence at his parish church in Lutterworth, near Rugby, in Northamptonshire. By this time he had entered the third and most important phase of his life. Going beyond his criticism of the abuses of church power and the conduct of its clergy, he began to attack Roman Catholic doctrine, just as Luther and Calvin later went beyond Erasmus in their theological reform.

As a philosopher Wycliffe argued against the spiritual sterility of contemporary skepticism; as a churchman he argued against the worldliness and corruption of the church; as a theologian he argued for the supremacy of the Bible and its message of God’s salvation by grace. It is this later Wycliffe whom we honor as the pioneer of our English language, our English Bible, and our Protestant religion.

Wycliffe preached the same message of God’s grace in Christ that sounded again in the Reformation two hundred years later:

Have a remembrance of the goodness of God, how he made you in his own likeness; and how Jesus Christ, both God and man, died so painful a death upon the cross, to buy your soul out of hell, even with his own heart’s blood, and to bring it to the bliss of heaven.8

Wycliffe’s preaching is concentrated in these few words from his sermon, “A Short Rule of Life for Priests, Lords,

and Laborers”:

At the end of the day, think about how you have offended God . . . and . . . how graciously God has saved you; not for your desert, but for his own mercy and goodness . . . and pray for grace that you may dwell and end in his true service, and real love, and according to your skill, to teach others to do the same.9

Wycliffe’s instruction to people seeking salvation anticipated the words of Luther, Calvin, and Knox: “Trust wholly in Christ; rely altogether on His sufferings; beware of seeking to be justified in any other way than by His righteousness. Faith in our Lord Jesus Christ is sufficient for salvation.”10

Wycliffe defined the church as the predestined body of the elect. The doctrine of election, going back to Augustine, who found it in the Bible and especially in the writings of the apostle Paul, had been rejected or ignored by the medieval church because it was a threat to the authority of the church and its sacramental system as the only means of salvation.

“Neither place nor human election makes a person a member of the church but divine predestination in respect of whoever with perseverance follows Christ in love,” wrote Wycliffe.11 As these words make clear, Wycliffe accompanied his insistence on the doctrine of predestination with equal emphasis on the necessity for Christians to live according to the Bible’s teaching by following Christ’s teaching and example.

Wycliffe denied the claim that the pope was head of the church and that people were subject to him for their salvation.

The only true head of the church was Christ, said Wycliffe. Because popes claimed what belonged only to Christ, Wycliffe described them as “antichrists.” God’s grace, he preached, was available to every person without the need to believe in the claims of any ecclesiastical leader.

Wycliffe rejected the Catholic teaching of transubstantiation of the bread and wine in the Eucharist into the body and blood of Christ. He believed that the elements remained what they were before the act of consecration, although “under the form of bread and wine is sacramentally the Body of Christ.”12

He sought to free people from their common superstitious and magical understanding of the Eucharist, and to show them its spiritual purpose and power. Like the later Reformers, Wycliffe claimed that he was not putting forth new teaching but restating and defending the doctrine of the ancient church against the innovations introduced by the “modern doctors.”13

Wycliffe’s Greatest Contribution

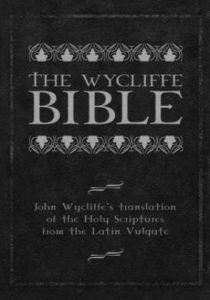

Wycliffe’s greatest contribution to church history was his elevation of the Bible to its supreme place and his insistence that it be made available to all Christians in their own language.14 In his book, The Truth of Holy Scripture, Wycliffe declared that Scripture was divinely inspired in every part and that it was the source of doctrine and the standard of life for all people, from peasants to kings and popes.

Wycliffe’s greatest contribution to church history was his elevation of the Bible to its supreme place and his insistence that it be made available to all Christians in their own language.14 In his book, The Truth of Holy Scripture, Wycliffe declared that Scripture was divinely inspired in every part and that it was the source of doctrine and the standard of life for all people, from peasants to kings and popes.

By the fourteenth century, a few portions of the Bible had been translated into Old English, but there was no version in the everyday language of most of the English people. John Wycliffe inspired and organized the work of providing such a Bible. There were two “Wycliffite” translations. The second and far superior was by John Purvey, an Oxford disciple of Wycliffe. Completed about 1395, a decade after Wycliffe’s death from natural causes on New Year’s Eve 1384, it was a translation of a translation, the Latin Vulgate translated into English.

Purvey used the dialect of London, like Chaucer in The Canterbury Tales, making Middle English the dominant form of the language. Wycliffe’s vision and Purvey’s Bible prepared the way for the work of William Tyndale and the translators of the Geneva Bible in the sixteenth century and the King James Version of 1611, as well as the many English translations that have followed.

Wycliffe, Pastor and Preacher

An energetic and effective preacher, John Wycliffe created and encouraged a group of preachers or itinerant evangelists to proclaim the Bible’s message throughout England. Many of these “poor preachers” were common people without a great deal of education. Wycliffe, a great scholar, wrote that “an unlearned man with God’s grace does more for the church than many [college] graduates.”15

An energetic and effective preacher, John Wycliffe created and encouraged a group of preachers or itinerant evangelists to proclaim the Bible’s message throughout England. Many of these “poor preachers” were common people without a great deal of education. Wycliffe, a great scholar, wrote that “an unlearned man with God’s grace does more for the church than many [college] graduates.”15

Wycliffe’s On the Pastoral Office expounds his view of what it meant to be a pastor. The book is divided into two parts: “holiness of life” and “wholesomeness of teaching.”16

In the second part he sets forth the duties of the pastor-preacher: “to feed his sheep spiritually on the Word of God,” “to purge wisely the sheep of disease, that they may not infect themselves and others as well,” and “to defend his sheep from ravening wolves.”17 The primary means of accomplishing these tasks is “sowing the Word of God among the sheep” by word and deed.

God ordains for a good reason that by the teaching of the pastor and his own manner of life his preaching to his sheep may be made efficacious, since this acts more effectively than mere preaching . . . The life of a good pastor is of necessity a mirror to be imitated by his flock.18

Wycliffe’s preachers were called Lollards by their enemies, a pejorative word meaning “mumblers.” Wycliffe instructed them:

Go and preach, it is the sublimest work; but imitate not the priests whom we see after the sermon sitting in the ale-house, or at the gaming table . . . After your sermon is ended, visit the sick, the aged, the poor, the blind and the lame and succour them.19

The parson in The Canterbury Tales was a Lollard.20 In the general prologue Chaucer introduces him:

There was also riding with us a good man of religion, the poor parson of a small town. He was poor in wealth, perhaps, but rich in thought and holy works. He was also a learned man, a clerk [a scholar or theologian], who preached Christ’s gospel in the most faithful fashion and who taught his parishioners the lessons of devotion. He was gracious, and diligent; in adversity, as he proved many times, he was patient . . . He had a large parish, with the houses set far apart, but neither rain nor thunder would prevent him from visiting his parishioners in times of grief or dearth . . . He gave the best possible example to his flock. Perform before you preach. Good deeds are more fruitful than good words . .. He . . . protected his flock from the wolves of sin and greed that threatened it. He was a true shepherd . . . He wanted to draw people to God with kind words and good deeds . . . He simply taught, and followed, the law of Christ and the gospel of his apostles.

Instead of a tale, the parson preached a sermon, a long one, praying that at the end of their journey God would guide and use him; he also reminded his fellow travelers that “our pilgrimage on earth is an image of the glorious pilgrimage to the celestial city.” He took his text from Jeremiah: “Stand upon the old paths and find from old scriptures the right way which is the good way.”21

The Lollards, without the intellectual support of Oxford and the protection of the ruling class, were forced to work with great caution. Not unlike the early Christians in the Roman Empire, they were heard of only when they came to the notice of the authorities.

For more than a hundred years, the bishops sought them out, seizing their fragments of manuscript Bibles, attempting to force them to recant, and burning some of them at the stake. Wycliffe’s preachers persevered, however, in the English Midlands and the Welsh border country, East Anglia and the west of England, and as far afield as Scotland.22

Wycliffe’s Reach

Wycliffe’s teaching spread far beyond England and Scotland to central Europe, through the political alliance between England and Bohemia, and influenced scholars and preachers including John Hus. A Bohemian psalter shows a picture of Wycliffe striking the spark, Hus kindling the coals, and Luther brandishing the lighted torch. Erasmus wrote to the pope in 1523, “Once the party of the Wycliffites was overcome by the power of the kings; but it was only overcome and not extinguished.”23

An unusual tribute to Wycliffe occurred in 1533, when the Protestant Reformer John Frith was burned at the stake. Shortly before his martyrdom, Frith praised the “sincere life” of John Wycliffe. It is the first recorded use of the word sincere in English to refer to a person. Previously the word was used to describe the purity of physical things—things whole and unadulterated. It was a good word for a later Protestant to use for “the morning star of the Reformation.”24

In 1415, more than thirty years after his death, the Council of Constance formally condemned forty-five “errors” of Wycliffe. Thirteen years later, in 1428, his bones were dug up and burned. The eloquent words of a seventeenth-century writer proved to

be true.

They burned his bones to ashes and cast them into the Swift, a neighbouring brook running hard by. Thus the brook conveyed his ashes into the Avon, the Avon into the Severn, the Severn into the narrow seas and they into the main ocean. And so the ashes of Wycliffe are symbolic of his doctrine, which is now spread throughout the world.25

Notes:

1. Daniel Neal, The History of the Puritans (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1824), 1:29.

2. Montagu Burrows, Wyclif’s Place in History (London: W. Isbister, 1884). Quoted in Christian History 2, no. 2: 2.

3. Matthew Spinka, ed., Advocates of Reform: From Wyclif to Erasmus (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1953), 24.

4. Douglas C. Wood, The Evangelical Doctor: John Wycliffe and the Lollards (Welwyn, Hertfordshire, England: Evangelical Press, 1984), 38.

5. Ibid., 76.

6. Ibid., 56.

7. Ibid., 97.

8. Ibid., 41.

9. Quoted in Christian History, 23.

10. Ibid., 25.

11. G.H.W. Parker, The Morning Star: Wycliffe and the Dawn of the Reformation (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1966), 37.

12. Ibid., 41.

13. Spinka, Advocates of Reform, 29.

14. Wycliffe’s example inspires the work of the Wycliffe Bible Translators, founded in 1934. In 2010 there were translations of the entire Bible or some portion of it in 2,500 of the 6,860 languages of the world. The Wycliffe Bible Translators and others are at work translating the Word of God into the remaining languages of the earth. See “A Fellow’s Journey from Washington to Wycliffe,” by Jeanne Thum in Knowing & Doing, Fall 2012.

15. Wood, Evangelical Doctor, 102.

16. Spinka, Advocates of Reform, 47.

17. Ibid., 48.

18. Ibid.

19. Wood, Evangelical Doctor, 87.

20. William Haller’s The Rise of Puritanism (New York: Harper, 1957) begins with a question: Who was the first Puritan? Haller answers that “Chaucer met one on the road to Canterbury and drew his portrait” (3).

21. Peter Ackroyd, The Canterbury Tales: Geoffrey Chaucer. A Retelling (New York: Viking Penguin, 2009), 16–17, 434.

22. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 994. With the Lollards, George Wishart found a safe haven during his preaching tours in Scotland of the 1540s; John Knox was active among them in the 1550s. “Lollards” was one of the first names given to British Protestants.

23. Wood, Evangelical Doctor, 135.

24. New York Times Book Review, August 12, 2012, 17.

25. Thomas Fuller, The Church History of Britain (1655; repr. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1845), 424.

David B. Calhoun

ProfessorDavid B. Calhoun, (1937-2021) was Professor Emeritus of Church History at Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri. A minister of the Presbyterian Church in America, he has taught at Covenant College, Columbia Bible College (now Columbia International University), and Jamaica Bible College (where he was also principal). Calhoun has served with Ministries in Action in the West Indies and in Europe and as dean of the Iona Centres for Theological Study. He was a board member (and for some years president) of Presbyterian Mission International, a mission board that assists nationals who are Covenant Seminary graduates to return to their homelands for ministry.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

A Welcome Change in Apologetics

by Randy Newman, Aimee Riegert on April 19, 2024We’re burdened for our friends who don’t know...Read More

-

Questions That Matter Podcast – Samuel James and Digital Liturgies

by Samuel James, Randy Newman on April 19, 2024

-

The Side B Stories – Dr. James Tour’s story

by Jana Harmon, James Tour on April 12, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Isn’t Morality Relative?

by Christopher L. Reese on April 1, 2024It is widely accepted in the Western world...Read More

-

Do Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God?

by Andy Bannister on March 1, 2024

-

Artificial Intelligence and Its Impacts on Humanity

by John Lennox on February 13, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

22140

GLOBAL EVENT: Keeping the Faith From One Generation To Another with Stuart McAllister and Cameron McAllister, 8:00PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=global-event-keeping-the-faith-from-one-generation-to-another-with-stuart-mcallister-and-cameron-mcallister-800pm-et&event_date=2024-05-17®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-05-17

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

GLOBAL EVENT: Keeping the Faith From One Generation To Another with Stuart McAllister and Cameron McAllister, 8:00PM ET

On May 17, 2024 at 8:00 pmSpeakers

David B. Calhoun

Professor

Team Members

David B. Calhoun

ProfessorDavid B. Calhoun, (1937-2021) was Professor Emeritus of Church History at Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri. A minister of the Presbyterian Church in America, he has taught at Covenant College, Columbia Bible College (now Columbia International University), and Jamaica Bible College (where he was also principal). Calhoun has served with Ministries in Action in the West Indies and in Europe and as dean of the Iona Centres for Theological Study. He was a board member (and for some years president) of Presbyterian Mission International, a mission board that assists nationals who are Covenant Seminary graduates to return to their homelands for ministry.