Back to series

Recommended Reading:

Download or Listen to Audio

C.S. Lewis on Heaven and Hell

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

The modern age in which we live, and with which C.S. Lewis contested throughout his writings, denies the supernatural. John Lennon brilliantly expressed this modern mind in his song “Imagine”: “Imagine there’s no heaven… No hell… Imagine all the people, living for today…”

Lennon was merely lyrically distilling the growing consensus of the modern mind that has been developing in Western culture since the Enlightenment. A hundred years earlier, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “Other world, there is no other world. Here or nowhere is the whole fact of the matter!”

1Lewis believed that a vigorous supernaturalism was essential to understanding Christianity.2 Central to Lewis’s supernaturalism was an unapologetic belief in heaven and hell. Without a supernatural world, especially heaven and hell, there is much about our lives, human experience, and Christianity that just doesn’t fit together.

As a scholar of medieval times, in which the entire culture lived and breathed the daily consequences of believing in the reality of heaven and hell, Lewis was equipped to see the far-ranging change and destructive consequences of the world moving into the modern era.

Think about it. We begin our education at age five or six and attend school six hours a day, five days a week, nine months a year, until we are eighteen, twenty-two, or older. We learn about physics, biology, math, chemistry; in short, we study the physical side of life. In our educational experience, heaven may not be denied. It is just ignored. Consciously or unconsciously, we get the point: matter is all there is; there is no other world!

And yet, while there is a roaring silence in the public square of our secular society, for many, including Christians, there is a firm belief in the spiritual dimension of reality. Only the spiritual, including heaven and hell, has little to do with our practical day-to-day conduct. For many sincere Christian believers, it is not that “matter is all there is”; it is “matter is all that matters.”

In an article in The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology, the authors observe, “Though few churchmen explicitly repudiate belief in a future life, the virtual absence of reference to it in modern hymns, prayers, and popular apologetics indicates how little part it plays in the contemporary Christian consciousness.”

3John Baillie, a Christian scholar of the middle twentieth century, wrote,

I will not ask how often during the last twenty-five years you and I have listened to an old-style warning against the fires of hell. I will not even ask how many sermons have been preached in our hearing about a future day of reckoning when men shall reap according as they have sown. It will be enough to ask how many [of those] preaching during these years, have dwelt on the joys of heavenly rest with anything like the old ardent love and impatient longing, or have spoken of the world now as a place of sojourn or pilgrimage.4

Hell in the Writings of C.S. Lewis

Lewis understood the disastrous consequences of the modern mind excluding the spiritual. Heaven and hell were prominent themes to much of his writings. Lewis addressed both in one of his earliest Christian books, The Problem of Pain, published in 1940. Surprisingly, at least to me, he first discusses hell. I know lots of people who believe in heaven but don’t believe in hell. It is not a popular doctrine. Lewis didn’t back away:

Lewis understood the disastrous consequences of the modern mind excluding the spiritual. Heaven and hell were prominent themes to much of his writings. Lewis addressed both in one of his earliest Christian books, The Problem of Pain, published in 1940. Surprisingly, at least to me, he first discusses hell. I know lots of people who believe in heaven but don’t believe in hell. It is not a popular doctrine. Lewis didn’t back away:

There is no doctrine which I would more willingly remove from Christianity than this, if it lay in my power. But it has the full support of Scripture and, specially, of Our Lord's own words; it has always been held by Christendom; and it has the support of reason. If a game is played, it must be possible to lose it.5

Lewis wrote that pain, though unpleasant, has an important and soul-shaping role in the development of human character. Yet, although pain may lead someone to repent, it also may lead to damnation—to hell. What if someone just won’t repent no matter how great the pain? “Some will not be redeemed.”

6To our modern ears, belief in hell feels harsh, even mean. However, not only do the Scriptures give abundant witness to the existence of hell; the very concept of justice—that at some point, in some way, everyone gets what they deserve—requires the existence of hell. Hell is necessary to make the world work and for values to have any meaning.

The doctrine of hell displays not merely the justice of God, but His grace as well. In hell, God makes room for those who are not interested in God. Lewis wrote, “I willingly believe that the damned are, in one sense, successful, rebels to the end; that the doors of hell are locked on the inside.”

7The work by Lewis that got his face on the cover of Time magazine in 1947, The Screwtape Letters, explored hell. By means of imaginary correspondence between a senior tempter named Screwtape and a junior devil named Wormwood, Lewis shows in practical and specific ways how hell is always working to influence us. For Lewis, it was not so much that we are possessed and controlled by demons from which we must be delivered; rather, it is that we are constantly and quietly influenced by hellish creatures, all day long, every day! It’s a battle all the way from here to eternity.

About the awareness of hell in the modern mind, Lewis, in Letter 7, has Screwtape write to the junior tempter, Wormwood,

Our policy, for the moment, is to conceal ourselves. Of course this has not always been so . . . If any faint suspicion of your existence begins to arise in his mind, suggest to him a picture of something in red tights, and persuade him that since he cannot believe in that (it is an old textbook method of confusing them) he therefore cannot believe in you.8

Lewis explored another dimension of the influence of hell in his children’s series, The Chronicles of Narnia. In The Silver Chair, two children from our world, Eustace Clarence Scrubb and Jill Pole, accompanied by a Marsh Wiggle (Don’t ask! You will have to read the book!) are sent by Aslan on a mission in Narnia to rescue the Prince Rilian, son of Caspian the Tenth. Their mission takes them to the Underland ruled by the Lady of the Green Kirtle, a witch. At one point, they are captured by the witch, and she seeks to place them under her spell. In the dark caverns of her Underland and in the depths of her castle, Lewis challenges us to see the modern mind working its enchantment in asserting there is no supernatural, no other world than this one.

Lewis explored another dimension of the influence of hell in his children’s series, The Chronicles of Narnia. In The Silver Chair, two children from our world, Eustace Clarence Scrubb and Jill Pole, accompanied by a Marsh Wiggle (Don’t ask! You will have to read the book!) are sent by Aslan on a mission in Narnia to rescue the Prince Rilian, son of Caspian the Tenth. Their mission takes them to the Underland ruled by the Lady of the Green Kirtle, a witch. At one point, they are captured by the witch, and she seeks to place them under her spell. In the dark caverns of her Underland and in the depths of her castle, Lewis challenges us to see the modern mind working its enchantment in asserting there is no supernatural, no other world than this one.

As the witch plays her mandolin-like instrument, in a sing-song voice she tells her captives that her world is the only world, that there is no other world except hers. Jill and Scrubb are almost overcome:

This time it didn't come into [Jill’s] head that she was being enchanted, for now the magic was in its full strength; and of course, the more enchanted you get, the more certain you feel that you are not enchanted at all. She found herself saying (and at the moment it was a relief to say):

“No. I suppose that other world must be all a dream.”

“Yes. It is all a dream,” said the Witch, always thrumming.

“Yes, all a dream,” said Jill.

“There never was such a world,” said the Witch.

“No,” said Jill and Scrubb, “never was such a world.”

“There never was any world but mine,” said the Witch.

“There never was any world but yours,” said they.

9In this spiritual battle, we see exactly what Malcolm Muggeridge, the great English literary critic warned of: “The only ultimate disaster that can befall us, I have come to realize, is to feel ourselves to be at home here on earth.”

10Lewis’s most extensive work on hell and heaven is The Great Divorce, published in 1945. The nineteenth-century author William Blake speculated that eventually heaven and earth would be unified into one eternal existence. Lewis thought this was seriously and significantly wrong. He wrote The Great Divorce to contest Blake.

The Great Divorce is an imaginative account of ghosts from hell getting a holiday visit to heaven. Lewis functions as a tour guide; through his experience we get insight into what he thought about hell. The initial scene is a dreary urban landscape such as one might see in the post-World War II London at twilight. (There is an underlying of twilight or dawn that permeates the narrative. Either night is coming or day is coming. The potential light change brings the anticipation of terror or of joy.)

The town extends through endless suburbs as residents are always moving farther and farther out and away from one another, as the inhabitants of the town are prickly and quarrelsome. As the bus from hell arrives at the edges of heaven, each ghost is met by a host, a “solid person” who shines with light. Each host welcomes the shadowy, hazy, smudgy-looking ghosts and invites them to stay. Each invitation leads to a conversation. By my count we overhear seventeen different conversations. Step-by-step, conversation-by-conversation, Lewis peels away the layers of self-deceit in the human soul and exposes the confusions of the modern mind. As one host says to the liberal clergy ghost who doesn’t believe in heaven:

The town extends through endless suburbs as residents are always moving farther and farther out and away from one another, as the inhabitants of the town are prickly and quarrelsome. As the bus from hell arrives at the edges of heaven, each ghost is met by a host, a “solid person” who shines with light. Each host welcomes the shadowy, hazy, smudgy-looking ghosts and invites them to stay. Each invitation leads to a conversation. By my count we overhear seventeen different conversations. Step-by-step, conversation-by-conversation, Lewis peels away the layers of self-deceit in the human soul and exposes the confusions of the modern mind. As one host says to the liberal clergy ghost who doesn’t believe in heaven:

Our opinions were not honestly come by. We simply found ourselves in contact with a certain current of ideas and plunged into it because it seemed modern and successful. At College, you know, we just started automatically writing the kind of essays that got good marks and saying the kind of things that won applause. When, in our whole lives, did we honestly face, in solitude, the one question on which all turned: whether after all the Supernatural might not in fact occur? When did we put up one moment’s real resistance to the loss of our faith?11

Lewis eventually encounters his own solid person/host, George MacDonald, the author whose imaginative works first opened his mind to the possibility of belief in God. The conversations between Lewis and MacDonald provide insights on the nature of the great divorce between heaven and hell.

“Milton was right,” said my Teacher. “The choice of every lost soul can be expressed in the words, ‘Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.’ There is always something they insist on keeping, even at the price of misery. There is always something they prefer to joy—that is, to reality. Ye see it easily enough in a spoiled child that would sooner miss its play and its supper than say it was sorry and be friends. Ye call it the Sulks. But in adult life it has a hundred fine names — Achilles’ wrath… Revenge and Injured Merit and Self-Respect and Tragic Greatness and Proper Pride.”

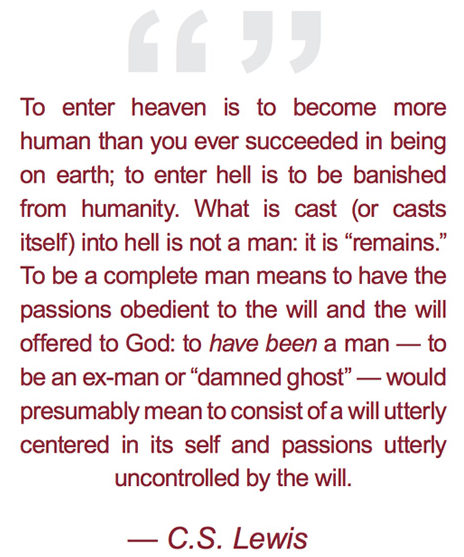

12Pride, and the sense of self, force a choice, on God’s part and ours.

There are only two kinds of people in the end: those who say to God, “Thy will be done”, and those to whom God says, in the end, “Thy will be done.” All that are in hell choose it. Without that self-choice there could be no hell. No soul that seriously and constantly desires joy will ever miss it. Those who seek find to those who knock, it is opened.

13These references from The Problem of Pain, The Screwtape Letters, The Silver Chair, and The Great Divorce are just tastes. Evil and hell make their appearance throughout the corpus of Lewis’s writings, from beginning to end.

Heaven in the Writings of C.S. Lewis

Like hell, the appearance of heaven surfaces in The Problem of Pain. At the beginning of the final chapter, Lewis wrote,

Like hell, the appearance of heaven surfaces in The Problem of Pain. At the beginning of the final chapter, Lewis wrote,

“I reckon,” said St. Paul “that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory that shall be revealed in us.” If this is so, a book on suffering which says nothing of heaven, is leaving out almost the whole of one side of the account. Scripture and tradition habitually put the joys of heaven into the scale against the sufferings of earth, and no solution of the problem of pain which does not do so can be called a Christian one.14

In The Problem of Pain Lewis first unveiled his argument for heaven as a fundamental human desire. This argument also shows up in his famous sermon preached at University Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Oxford, June 8, 1941. He maintained that the hunger for heaven is the secret subterranean motivation that everyone has and that it is present in everything we do.

Heaven is not only the central motivation of every being, but it is also the fulfillment of all our desires. We will discover that there is a place in heaven that is purposely shaped for each soul. It is in heaven that we discover who we are and what we are made for.

The self — “the golden apple of selfhood,” Lewis calls it at the end of the final chapter of The Problem of Pain — if surrendered to God becomes the great reward in heaven such that we find our hunger for ourselves and community deeply satisfied as we enter into a dance of creation that fills us with eternal and unspeakable joy. Lewis also writes about this eternal dance in the concluding pages of Perelandra, the second volume of his science fiction trilogy, published in 1943.

The self — “the golden apple of selfhood,” Lewis calls it at the end of the final chapter of The Problem of Pain — if surrendered to God becomes the great reward in heaven such that we find our hunger for ourselves and community deeply satisfied as we enter into a dance of creation that fills us with eternal and unspeakable joy. Lewis also writes about this eternal dance in the concluding pages of Perelandra, the second volume of his science fiction trilogy, published in 1943.

As we turn from The Problem of Pain to the sermon The Weight of Glory, written in the same period of Lewis’s life, we see that he writes of the spell of modernity that denies the reality of heaven:

You and I have need of the strongest spell that can be found to wake us from the evil enchantment of worldliness which has been laid upon us for nearly a hundred years. Almost our whole education has been directed to silencing this shy persistent, inner voice; almost all our modern philosophies have been devised to convince us that the good of man is to be found on this earth.15

Once we break the spell of this age, then heaven and life after death become something we can really look forward to!

At present we are on the outside of the world, the wrong side of the door. We discern the freshness and purity of morning, but they do not make us fresh and pure. We cannot mingle with the splendors we see. But all the leaves of the New Testament are rustling with the rumour that it will not always be so. Some day, God willing, we shall get in.

16The Weight of Glory, a short essay of fifteen pages, is worth reading again and again. I find that every time I do, it stirs in me longings and hungers for heaven that I experience nowhere else!

16The Weight of Glory, a short essay of fifteen pages, is worth reading again and again. I find that every time I do, it stirs in me longings and hungers for heaven that I experience nowhere else!

Shortly after publishing The Problem of Pain and preaching The Weight of Glory, Lewis was invited to deliver a series of radio talks on the BBC to provide spiritual encouragement to Britain in the depths of World War II. Eventually these radio talks would be published in 1952 under the title Mere Christianity.

In “books” 1 and 2 of Mere Christianity, Lewis begins by introducing the moral argument for the existence of God, and he then moves on to what Christians believe. In the final segments of his radio broadcasts, books 3 and 4 of Mere Christianity, he gives his version of essential Christian beliefs and behavior. Not surprisingly the doctrine of heaven is central.

In book 3, he further explains his argument from desire, introduced in The Problem of Pain,

Creatures are not born with desires unless satisfaction for those desires exists. A baby feels hunger: well, there is such a thing as food. A duckling wants to swim: well, there is such a thing as water. Men feel sexual desire: well, there is such a thing as sex. If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world. If none of my earthly pleasures satisfy it, that does not prove that the universe is a fraud. Probably earthly pleasures were never meant to satisfy it, but only to arouse it, to suggest the real thing.17

For Lewis, hope for heaven is not pie-in-the-sky dreaming. It is the essential way of connecting heaven and earth:

…a continual looking forward to the eternal world is not (as some modern people think) a form of escapism or wishful thinking, but one of the things a Christian is meant to do. It does not mean that we are to leave the present world as it is. If you read history you will find that the Christians who did most for the present world were just those who thought most of the next… It is since Christians have largely ceased to think of the other world that they have become so ineffective in this one. Aim at Heaven and you will get earth “thrown in”: aim at earth and you will get neither.

18Finally, we look again at Lewis’s teaching, not only on hell but also on heaven, through The Great Divorce. As Lewis joins the other shadowy, insubstantial, quarrelsome beings in their bus trip from the dreary town on the edges of hell to the bright and shiny edges of heaven, we move to a large wide open spacious realm that is solid and “heavy”:

18Finally, we look again at Lewis’s teaching, not only on hell but also on heaven, through The Great Divorce. As Lewis joins the other shadowy, insubstantial, quarrelsome beings in their bus trip from the dreary town on the edges of hell to the bright and shiny edges of heaven, we move to a large wide open spacious realm that is solid and “heavy”:

It was the light, the grass, the trees that were different; made of some different substance, so much solider than things in our country that men were ghosts by comparison. Moved by a sudden thought, I bent down and tried to pluck a daisy which was growing at my feet. The stalk wouldn’t break. I tried to twist it, but it wouldn’t twist. I tugged till the sweat stood out on my forehead and I had lost most of the skin off my hands. The little flower was hard, not like wood or even like iron, but like diamond. There was a leaf — a young tender beech — leaf, lying in the grass beside it. I tried to pick the leaf up: my heart almost cracked with the effort, and I believe I did just raise it. But I had to let it go at once; it was heavier than a sack of coal.19

His image of heaven is so different from popular conceptions of a vaporous world in the sky filled with white clouds populated with little cherubs stroking golden harps. I can’t help but think that Lewis was having fun with the Hebrew word for “glory,” which means “heavy.”

The process of transforming from a ghost to a solid person takes place as we choose God:

But the whole thickening treatment consists in learning to want God for his own sake.20 Human beings can’t make one another really happy for long . . . You cannot love a fellow creature fully until you love God.21 There is but one good; that is God. Everything else is good when it looks to him and bad when it turns from Him.22

Lewis has lots of questions for his host MacDonald and finally reaches a limit beyond which he cannot go. Instead of speculating, the issue is not about “what if,” but about the choices that we make. Lewis’s host concludes their conversation: “Ye saw the choices a bit more clearly than ye could see them on earth: the lens was clearer. But it was still seen through the lens. Do not ask of a vision in a dream more than a vision in a dream can give.”23

Conclusion

For most of us, whether we know it or not, our default mind-set is modern. In contrast, heaven and hell are central and integral to all of Lewis’s thought. Those of us who live in a modern de-super naturalized world need the wonderful, varied corpus of his writings to reshape our thinking and our living.

In conclusion, we return to Lewis’s sermon The Weight of Glory. Lewis writes that heaven and hell are the two possible futures that await us.

It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilization — these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendours.24

|

Notes: |

|||

Stephen Eyre

CSLI City Director, Cincinnati

Stephen Eyre is the Cincinnati City Director for the C.S. Lewis Institute. He is also the Minister of Congregational Development at Madeira-Silverwood Presbyterian Church as well as the Executive for Ministry Support for the 40 Day Prayer Covenant. Stephen is the author of many books and Bible study guides such as Christian Beliefs (InterVarsity Press), Ordinary People Extraordinary God: 17 Personal Stories of Lives Transformed by the Love of God (High Ridge Books), Patience: The Benefits of Waiting (Zondervan), and Spiritual Disciplines (Zondervan). He graduated from Covenant Seminary in St. Louis Missouri.

Recommended Reading:

Wayne Martindale, Beyond the Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis on Heaven and Hell (Crossway, 2005)

C.S. Lewis’s fiction is rich with reflections on the afterlife. For many, reading his books helps in forming a more vivid understanding of Heaven and Hell. In this book, Lewis scholar Wayne Martindale uses some of Lewis’s best-loved fiction as an imaginative complement to his discussion on eternity.

Those who know Lewis’s work will enjoy Martindale’s thorough examination of the powerful images of Heaven and Hell found in Lewis’s fiction, and all readers can appreciate Martindale’s scholarly yet accessible tone. Read this book, and you will see afresh the wonder of what lies beyond the Shadowlands.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

The Side B Stories – Dr. James Tour’s story

by Jana Harmon, James Tour on April 12, 2024From a secular Jewish home, scientific scholar and...Read More

-

Why are Christians so Bad?

by Paul Joen on April 5, 2024

-

Questions That Matter Podcast – Dai Hankey and Gospel Hope for Weary Souls

by Randy Newman, Dai Hankey on April 5, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Isn’t Morality Relative?

by Christopher L. Reese on April 1, 2024It is widely accepted in the Western world...Read More

-

Do Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God?

by Andy Bannister on March 1, 2024

-

Artificial Intelligence and Its Impacts on Humanity

by John Lennox on February 13, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

20599

GLOBAL EVENT: 2024 Study Tour of C.S. Lewis’s Belfast & Oxford

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=global-event-2023-study-tour-of-c-s-lewis-belfast-oxford-2&event_date=2024-06-22®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-06-22

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

GLOBAL EVENT: 2024 Study Tour of C.S. Lewis’s Belfast & Oxford

On June 22, 2024 at 12:00 pmat Belfast, Northern Ireland & Oxford, EnglandSpeakers

Stephen Eyre

CSLI City Director, Cincinnati

Team Members

Stephen Eyre

CSLI City Director, Cincinnati

Stephen Eyre is the Cincinnati City Director for the C.S. Lewis Institute. He is also the Minister of Congregational Development at Madeira-Silverwood Presbyterian Church as well as the Executive for Ministry Support for the 40 Day Prayer Covenant. Stephen is the author of many books and Bible study guides such as Christian Beliefs (InterVarsity Press), Ordinary People Extraordinary God: 17 Personal Stories of Lives Transformed by the Love of God (High Ridge Books), Patience: The Benefits of Waiting (Zondervan), and Spiritual Disciplines (Zondervan). He graduated from Covenant Seminary in St. Louis Missouri.