Back to series

Recommended Reading:

Download or Listen to Audio

Reaching the Resistant

Click here to open a Print-Friendly PDF

If there is something common in all of us, it is our deep need for acceptance and love, for meaning and fulfillment in life, and to know what is true and real. Yet we’ve all seen many flatly reject God even though He is, and can be shown to be, the source of all we desire.

If there is something common in all of us, it is our deep need for acceptance and love, for meaning and fulfillment in life, and to know what is true and real. Yet we’ve all seen many flatly reject God even though He is, and can be shown to be, the source of all we desire.

When you see or hear of someone resisting God, perhaps you’ve wondered: If God is good, the source of abundant life, of unconditional love, of belonging, acceptance and deep satisfaction; and if God is true and can be shown through evidence, reason, and revelation, why does someone rebuff what is good, true, and life giving?

Why resist who and what we all ultimately desire? Further, what motivates someone to become open toward God, toward life that is truly life? What ways and means does God use to draw those who resist Him toward Himself? Is anyone outside of the Father’s reach?

These questions fueled me to take an investigative journey engaging more than fifty former secular atheists to discover why they held resistance toward religious belief, the catalysts opening their minds and hearts toward change, and the reasons they finally became followers of Jesus Christ. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of them reported no amount of evidence would have convinced them of the truth of any other worldview than atheism.

This response begs the question of their intellectual honesty and helps answer the question as to why substantive evidence often seemingly falls flat. Further, in light of such heightened resistance, it also piques interest as to what caused such defiant walls to be built and what eventually caused such stalwart barriers to fall down.

As we consider these issues, it is important first to realize that most people would say no to any type of religious conversion. Resistance is the normal or typical reaction of individuals and societies to conversion attempts, according to leading researcher Louis Rambo.1

Becoming a Christ follower entails more than merely changing one’s mind about belief in God; it demands reconsideration of life’s biggest questions as well as deep commitment to a new way of living. As such, the cost of belief for both mind and heart is too great a consideration for most.

And although many resistant to God will first provide intellectual reasons for disbelief, it’s also valuable to be aware that their beliefs are not formed in a vacuum, but rather are often wrapped up in a story of how they got there and why they believe what they believe.

We are human beings with minds, emotions, and wills, influenced by our families, friends, experiences, culture, social media, education, spiritual influences, and desires. Expecting the resister’s walls to easily crumble with an apologetic argument may be unrealistic, since it may be bouncing off of years of experiential, emotional, volitional, intellectually rationalized layers solidly and slowly built brick by brick.

Consider the circumstances upon which four individuals rejected belief in God:

• As a child, Matt occasionally visited church and was taught Jesus loved him. But at age seven, his house caught on fire, causing the death of two brothers and burning his young faith to the ground. Guilt-ridden, depressed, and angry, Matt gradually developed an impassioned hatred for God, even refusing to step foot in any church building for a wedding or funeral, at great social expense. He also bolstered an arsenal of rational arguments to support his underlying emotional angst, fiercely refuting any alternative evidence for the reality of God. God is not good or true. What would it take to soften his resistance?

• Joe was raised in a home absent of religious influence apart from his mother’s fluid “new age” spirituality. Present, however, was his father’s “high-brow scientific intellectualism.” Instead of a Bible, Carl Sagan’s Cosmos found a steady home on the coffee table.

• Joe was raised in a home absent of religious influence apart from his mother’s fluid “new age” spirituality. Present, however, was his father’s “high-brow scientific intellectualism.” Instead of a Bible, Carl Sagan’s Cosmos found a steady home on the coffee table.

Captain of the debate team, Joe perceived himself to be extremely bright and competent on the academic playground, a self-proclaimed nihilist at age fourteen. His friends constituted a “disproportionate number of antagonistic atheists and agnostics” who enjoyed ridiculing Christians, readily defeating any argument. God is not true. What would it take to soften his resistance?

• As a child Susan believed in God but she became resistant due to the legalistic, oppressive experience of Christian “religion” in her life. This distorted experience was compounded by personal pain and disappointment with God due to the sudden death of a close friend. She found beauty in other religions that seemed lacking in Christianity. God is not good. What would it take to bring her back to belief?

• Paul had everything he ever wanted in life, highly successful by the world’s standards with no felt need for God. His personal, social, and intellectual world lacked any substantive or personal exposure to Christian faith apart from one esteemed, erudite grandfather. Regardless, he viewed Christians as extraordinarily strange, as a group of whom he would be exceedingly ashamed to be associated. Belief in God would have interfered with his lifestyle. God is not good or true. What motivated him toward Christianity?

It’s likely someone will have varied reasons for believing that God is not real.

Although intellectual reasons are often center-stage as the motivation for resistance against God, we need to pull back the curtain and acknowledge other potential life influences as well.

As seen in these four stories, resistance against God and Christian belief is influenced by sociocultural environment (family, friends, community, education, culture), sense of identity (intelligent, rational, autonomous), intellectual and emotional doubts (“Where is God?”), personal experiences (negative “How could God?” and positive “no need for God”), as well as moral choices. We are more than merely rational beings. We are whole persons whose conscious rational choices are formed by many things inside and outside of us.

One of the most fascinating research findings arose when participants were asked why they didn’t believe God was real. The most common response was not the lack of objective evidence to confirm God’s existence, but rather the lack of subjective evidence for God. That is, they did not personally see or feel God’s presence in their lives or in the world.

But many also confirmed a seeming lack of scientific and reasoned evidence, asserting the irrationality of belief and apparent irreconcilability of science and religious belief. Simply put, if belief in God is not plausible personally and/or intellectually, He is not worthy of pursuit.

The resistant person may believe primarily that “God is not true.”

Getting to the root of a skeptic’s objection is important, according to one former atheist in the study. Identifying different types of skepticism leads toward asking appropriate probing questions.3 If you went to the doctor for a chronic headache, and the doctor treated your foot, you would not feel heard; the treatment would have no positive effect on the originating complaint.

Similarly, it is important to discover a skeptic’s particular areas of doubt, to intentionally guide the skeptic to discover the holes in a personal worldview. This is done through good listening, strategic question asking, and leaning into the ready guidance of the Holy Spirit. We want to engage thoughtfully with the doubts they are offering and questions they are asking, not the ones they aren’t.

If someone is truly seeking after truth and is willing to “go where the evidence leads,” the Christian worldview stands unparalleled in its internal coherence, its external correspondence with reality, and its comprehensive explanatory nature.

If someone is truly seeking after truth and is willing to “go where the evidence leads,” the Christian worldview stands unparalleled in its internal coherence, its external correspondence with reality, and its comprehensive explanatory nature.

When exploring and realizing the limitations of their own worldviews, more than one-third of the resistant atheists in the research study began to experience cognitive dissonance when they could not explain, for example, objective moral duties and values or the origin and design of the universe and life.

As assessed by Francis Schaeffer years ago, there is often a “disconnect between what an unbeliever might profess and his or her deeply held convictions or practice.

Believing every human being to know God (Romans 1:18-21), [Schaeffer] understood that however bold their claims might be about meaninglessness or atheism, their lives betrayed a deeper awareness.” This tension can become a pivotal catalyst toward openness for many who are willing to deal with the conflict in their own view of life and the world as they know and experience it.4

Others became surprisingly softened toward the true reality of God through an effort to prove the opposite. More than one-third pursued the truth of Christianity in order to disprove it, yet they found the Christian worldview to provide the best explanation for “the way things are” in reality. As one person said, “Trying on other worldviews was like sorting through a box of wires. When I finally got down to what the meat of Christianity was, it was the only thing that kind of shocked back, like grabbing a live wire.”

During this exploration phase, it is important that genuine seekers find those whom they can intellectually respect, who have not only taken time to learn the evidential foundation of the Christian worldview, but also to understand the seeker’s perspective on reality.

Relational patience is often required in allowing seekers to discover the inconsistencies, contradictions, and insufficiencies of their own worldview, to reach a point of dissatisfaction that creates openness toward another perspective.

In the “thinking person’s journey,” according to Os Guinness, someone will not be willing or open genuinely to seek after another perspective until and unless that person is first dissatisfied with his or her own view of the world.

Discontent fosters awareness of need for a better explanation for reality. However, it’s important to realize that “Arguments can indeed shape a worldview, but that’s only true if someone is in a state of mind where truth is valued above all other things.”5

If someone does not want to move toward God and/or Christianity, this volitional resistance may prevent acknowledgment of the truth of any compelling evidence, reason, or argument for an alternative perspective.

To some extent, everyone has a confirmation bias, pursuing that which we want to be true. We see what we seek. According to Dallas Willard, “If you believe from the outset there is no knowledge (of God), you won’t seek it. Then your belief that there is no knowledge will confirm itself.”6

Further, in presenting evidence to someone who holds a differing perspective, some may experience “the backfire effect.” When encountering challenging information, resistance may be increased rather than resolved. The wall of opposition becomes more fortified. Attention must then be turned beneath the surface of intellectual obstacles to discover the personal, volitional barriers in the foundation below.

The resistant person may believe primarily that “God is not good.”

Someone may provide an intellectual basis against Christianity but “real reasons” for disbelief reside much deeper. If belief in God is not attractive, it is not worthy of pursuit. As atheists, most (82%) had not engaged with Christians or Christianity in any personal sense; they had formed a distasteful “bumper sticker understanding” from a cultural distance.

In such case, evidence, reason, and argument may merely bounce off of an impenetrable surface without effect.

The distaste for moral authority and accountability may also drive resistance against the goodness of God. Forty-five percent admitted a lack of desire for the truth of Christianity, one-third due to its moral constraints and/or perceived lack of need. As one person stated, “I had genuine intellectual doubts, but insincere motives” for continuing in his current immoral lifestyle.

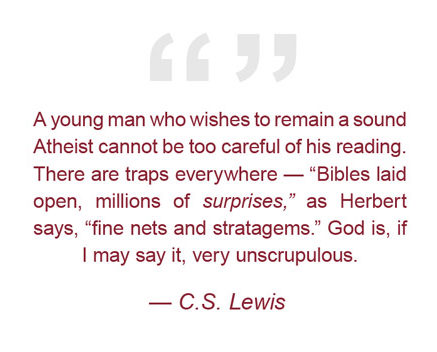

This kind of resistance is commonly experienced. This creaturely rebellion against the Creator is writ large across the story of mankind in the biblical narrative. In his personal journey, C.S. Lewis described his pre-conversion struggle against God:

But, of course, what mattered most of all was my deep-seated hatred of authority, my monstrous individualism, my lawlessness. No word in my vocabulary expressed deeper hatred than the word Interference. But Christianity placed at the center what then seemed to me a transcendental Interferer. If its picture were true then no sort of “treaty with reality” could ever be possible. There was no region even in the innermost depth of one's soul (nay, there least of all) which one could surround with a barbed wire fence and guard with a notice No Admittance. And that was what I wanted; some area, however small, of which I could say to all other beings, “This is my business and mine only.”7

The cruel irony is that life apart from God yields perceived liberation but in reality no free will; perceived dignity but in reality loss of any special status; perceived self-creation but in reality no ultimate purpose, meaning, or hope, “nothing but blind pitiless indifference”;8 perceived rationality but in reality no real “mind” nor any way to trust it; perceived love and virtue but in reality nothing but complex chemical reactions and impulses. The logical endpoint of secular atheism is emptiness and despair; loss of goodness and truth as we know it and experience it.

How, then, can this autonomous fire be quenched? How can a false dictatorial vision of God be transformed into one of good, loving protection and direction toward human flourishing? Perhaps, as seen in the stories above, soul-crushing life events and/or prolonged experiences cause deep conflicting questions to rise to the surface, turn grief and loss into anger, blame, resentment, and contempt against all things religious, including God and His representatives. How can the wounds be healed, the pain soothed enough to feel the compassion and care of a loving Father?

It may be that someone has never been exposed to authentic Christianity but rather only an unattractive culturally created caricature. Or personal experience with a negative, hypocritical form of Christianity may have informed their negative impression of Christians and belief in God.

Christians were viewed as intolerant, delusional, hypocritical, and uneducated. This generalized negative stereotyping of belief in God and Christianity begs the question — how can the repugnant caricatures be countered? How do we counter negative caricatures of Christians as uneducated, superstitious, defensive, fearful, and uncaring?

“Show and tell” of the goodness and truth of God.

Listen.

In reaching those who are resistant to God, we experientially affirm both the truth and goodness of God. Sometimes that’s done together. Our primary focus should be first to listen, to seek toward understanding not only what they believe but also who they are. We value them through taking time to learn about them through our respectful words and tone.

We show them that we are interested in their lives and desire the best for them, and that we are trustworthy, careful with what they share. We seriously consider their intellectual doubts and resistance, but also intentionally learn more about how and why those beliefs were formed.

We discover their intellectual and personal barriers toward belief. Ask them to “tell their story.” This authentic, interested engagement values what they think and who they are and begins to soften hard edges and breach resistant walls. Also, listen to the Spirit of God, for His promptings, to make the most of every opportunity. Remember, the resistant person’s heart is ultimately opened through the kindness and mercy of God. We are all utterly dependent on Him.

Live.

We live out the truth and goodness of God. When we consider what truth is, we typically think of it as verifiable intellectual concepts that, once demonstrated, are sufficient for belief. However, we know that truth is also a person. Truth is personified in Jesus Christ. To the God-resistant people around Him, Jesus not only demonstrated “true truth” through His teaching but also experientially through His virtuous, surrendered, grace-filled, other-centered life.

The resistant were attracted to Jesus and wanted to eat with Him, listen to Him, and be with Him. Their experience with Him verified His words, His claims about Himself, and about His value of and love for them. As human beings longing for acceptance and love, they were drawn to the abundant life which He lived and of which He spoke.

As His followers, we should take cue from Him. Our words should match our lives. The truths and promises of God should be shown not only in our proclamation of truth claims but also demonstrated in and through us. Yes, Peter urges us to “always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have” (1 Pet. 3:15 NIV), to know and proclaim what is conceptually true. That is our mandated responsibility.

Notice, though, what he says just before that, in the same verse: “But in your hearts revere Christ as Lord.” The front-door “Christ-living” often precedes openness toward “Christ-telling.” Unbelievers should not be given reason to malign or dismiss Christ out of hand because of what they are seeing and experiencing of our lives. We represent the person of Jesus and the message of the gospel. A joy-filled life of integrity, surrender, and love opens the door to grant a hearing of His truth.9 One former atheist summed up — the best way to open a resistant mind and heart is to “live an available life,” generously giving of ourselves to others. Our openness toward them leads them to openness toward us, toward Jesus, and the gospel.

Love.

The vast majority of former atheists in my research, 80 percent, were first drawn to the goodness of Christianity, that it was worth pursuing in the first place before they were willing to seriously consider whether or not it was true. And similarly, 82 percent were introduced to the goodness of God through meeting an authentic Christ follower.

The vast majority of former atheists in my research, 80 percent, were first drawn to the goodness of Christianity, that it was worth pursuing in the first place before they were willing to seriously consider whether or not it was true. And similarly, 82 percent were introduced to the goodness of God through meeting an authentic Christ follower.

This is an extraordinary finding! Oftentimes we present information first and wonder why it falls flat. Perhaps we need to reconsider the context and preamble upon which they hear it. Perhaps the stage hasn’t been set.

Perhaps the intellectual truth has not yet been made “attractive” by their getting to know Christians who counter negative stereotypes they have heard about. Meeting and getting to know authentic Christ followers may lead them to have a more willing and open mind about Christianity.

Love authenticates the reality of God, invites curiosity and enjoins desire of unbelievers to become interested in knowing more about the source of abundant life and true truth. The resistant see and feel God through the witness of the Spirit in us, His hands and feet, and stony hearts begin to melt toward flesh. They begin to see that God is good and experientially true. He meets their deepest needs for love, acceptance, value, belonging, and forgiveness.

Learn.

However, even if negative stereotypes begin to dissolve, the resistant typically do not want to change their life perspective, particularly to a religious view, unless they believe it to be intellectually true, worth the change. And there are those who are intent on finding truth, regardless of the perceived negative cost.

However, even if negative stereotypes begin to dissolve, the resistant typically do not want to change their life perspective, particularly to a religious view, unless they believe it to be intellectually true, worth the change. And there are those who are intent on finding truth, regardless of the perceived negative cost.

Approximately one of every five began their pursuit of Christianity through an intellectual means. Consequently, as ambassadors of Christ, we must learn well our own biblical worldview but also the worldview perspective of the one who is resistant.

We need to embrace the fullness of God’s revelation to us through creation, through our conscience, through Scripture, as well as through Christ, so that we can live our lives meaningfully. The grand story of God is evident in all we know and experience in the universe and in our humanity. Let us be diligent to demonstrate the undeniable greatness and presence of God as in and through all of reality!

Further, a humble attitude goes a long way toward sparking openness in another. We need to be willing to learn from one another. One former atheist, a PhD biologist, noted that her willingness to investigate Christianity was modeled by the Christian with whom she interacted. She stated candidly, “If he would not have been open toward learning from me in the process of journeying toward truth, I would not have been open toward learning from him.”

Resistance to God is not new. But, no one is outside of God’s reach.

Seventeenth-century polymath Blaise Pascal noted that;

Men despise religion. They hate it and are afraid it might be true… To cure that we have to begin by showing that religion is not contrary to reason. That it is worthy of veneration and should be given respect. Next it should be made lovable, should make the good wish it were true. Then show that it is indeed true.10

C.S. Lewis proves a pivotal exemplar. His resistance to God was certainly grounded in intellectual doubts for which he required a robust response, but those objective questions were accompanied by moral resistance as well as a reality of personal pain experienced through unanswered childhood prayer (his mother’s death) and sobering exposure to evil (through war). Yet joy haunted his spirit as something good and experientially real, something undeniable yet unexplainable within his reductionistic atheism.

Something good. Something true. Someone real. He found the eternal source of all life, love, truth, and well-being.

|

Notes:

|

|||

Jana Harmon

Senior Fellow For Christian Apologetics, CSLI Jana Harmon, Ph.D, is the Senior Fellow For Christian Apologetics for the C.S. Lewis Institute and a Teaching Fellow for C.S. Lewis Institute Atlanta. She serves on the Atlanta Advisory Board and as an Adjunct Professor of Cultural Apologetics at Biola University. Her doctoral research studied the religious conversion of atheists to Christianity looking at the perspectives and stories of 50 former Atheists. She views apologetics through a practical, evangelistic lens. She is the host of the podcast eX-skeptic for the C.S. Lewis Institute. Jana received her PhD from the University of Birmingham, England.

Recommended Reading:

Andy Bannister, The Atheist Who Didn’t Exist: Or the Dreadful Consequences of Bad Arguments (Lion Hudson, 2015)

In the last decade, atheism has leapt from obscurity to the front pages: producing best-selling books, making movies, and plastering adverts on the side of buses. There’s an energy and a confidence to contemporary atheism: many people now assume that a godless scepticism is the default position, indeed the only position for anybody wishing to appear educated, contemporary, and urbane. Atheism is hip, religion is boring. Yet when one pokes at popular atheism, many of the arguments used to prop it up quickly unravel. The Atheist Who Didn’t Exist is designed to expose some of the loose threads on the cardigan of atheism, tug a little, and see what happens. Blending humour with serious thought, Andy Bannister helps the reader question everything, assume nothing and, above all, recognise lazy scepticism and bad arguments. Be an atheist by all means: but do be a thought-through one.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

The Importance of Imagination for C.S. Lewis and for Us

by Arthur W. Lindsley, Aimee Riegert on September 5, 2025C.S. Lewis’ enduring influence lies in his rare...Read More

-

The Four Gospels: Trustworthy, Forged, or Corrupted?

by Peter J. Williams, Kathleen Noller on September 5, 2025

-

Looking for Meaning – Allison Leonhardt’s story

by Jana Harmon, Allison Leonhardt on August 29, 2025

-

Recent Publications

What is the Christian response to transgenderism?

by Alycia Wood on August 25, 2025Many modern people believe the universe is governed...Read More

-

Cosmic Chemistry: Do God and Science Mix?

by John Lennox on August 15, 2025

-

When Truth Is Lost, Goodness Distorted, And Beauty Forgotten

by Thiago M. Silva on July 29, 2025

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

24720

The Adventure of Joining God in His Work Live Online Small Group 7:00 PM CT

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=the-adventure-of-joining-god-in-his-work-live-online-small-group-700-pm-ct&event_date=2025-09-16®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2025-09-16

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

The Adventure of Joining God in His Work Live Online Small Group 7:00 PM CT

On September 16, 2025 at 7:00 pmSpeakers

Jana Harmon

Senior Fellow For Christian Apologetics, CSLI

Team Members

Jana Harmon

Senior Fellow For Christian Apologetics, CSLIJana Harmon, Ph.D, is the Senior Fellow For Christian Apologetics for the C.S. Lewis Institute and a Teaching Fellow for C.S. Lewis Institute Atlanta. She serves on the Atlanta Advisory Board and as an Adjunct Professor of Cultural Apologetics at Biola University. Her doctoral research studied the religious conversion of atheists to Christianity looking at the perspectives and stories of 50 former Atheists. She views apologetics through a practical, evangelistic lens. She is the host of the podcast eX-skeptic for the C.S. Lewis Institute. Jana received her PhD from the University of Birmingham, England.