Back to series

Recommended Reading:

The City of GOD

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

The City of God by St. Augustine is recognized as one of the most influential books in history. It was written (ca. AD 413–426) to respond to claims that Christians were responsible for the sack of Rome because Christians had angered the pagan gods, who were no longer being worshiped as they had been before. It contrasts “the City of God” with “the City of Man” and addresses a wide range of philosophical subjects.

Introduction

Ambitious pursuits; corrupt desires; friendship; pride; vocation; evil and the goodness of God; lust;1 what psychologists call “family of origin issues”; and so much more. Sounds like a TV soap opera, doesn’t it? Actually, it’s the life of St. Augustine.

My attraction to Augustine is sparked by the same thing that attracts me to scriptural characters like David, Habakkuk, Mary Magdalene, and Peter. We see humanity, warts and all, but we also see the dazzling display and glorious triumph of God’s grace over any and all sin. As St. Paul says, “For if by the transgression of the one, death reigned through the one, much more those who receive the abundance of grace and of the gift of righteousness will reign in life through the One, Jesus Christ” (Rom. 5:17).

My attraction to Augustine is sparked by the same thing that attracts me to scriptural characters like David, Habakkuk, Mary Magdalene, and Peter. We see humanity, warts and all, but we also see the dazzling display and glorious triumph of God’s grace over any and all sin. As St. Paul says, “For if by the transgression of the one, death reigned through the one, much more those who receive the abundance of grace and of the gift of righteousness will reign in life through the One, Jesus Christ” (Rom. 5:17).

2Augustine lived during a tumultuous and transitional time. The explosive growth of Christianity, coupled with the fall of the Western Roman Empire,3 made for very interesting challenges.

The era also treated Christianity with more gravity than today. Even the well-known skeptic Bertrand Russell admitted that “Christian” no longer has the “full-blooded meaning” that it had during past ages. According to Russell, the times of luminaries like Augustine and Aquinas were characterized by an acceptance of “a whole collection of creeds which were set out with great precision, and every syllable of those creeds you believed with the whole strength of your convictions.”

4Augustine’s influence on the Christian church is massive.5 Many see him as the greatest influence on the church between the time of Paul and Martin Luther.6 Both Protestants and Roman Catholics see him as a pivotal figure. Among other things, Protestants like him for his realistic view of human nature. Roman Catholics appreciate his view of the sacraments and the church. Eastern Orthodox Christians have concerns with certain areas of Augustine’s teaching.

7Equally massive is Augustine’s writing output — some 5 million words! Remember, this is done without a word processor! More of Augustine’s work survives than any other ancient writer.8 Writing in the 1130s, Hugh of St. Victor said this about Augustine’s amazing productivity in relationship to such major figures as Origen and Jerome: “But Augustine, in mental ability or in self-knowledge, surpasses the studious efforts of all these men. He wrote so many things that no one finds enough days and nights in which to write or indeed even to read his books.”9 He used several copyists and, as Garry Wills put it, Augustine “paced about as he dictated, a reflection of the mental restlessness and energy conveyed in the very rhythms of his prose.”10 It is one thing to write prolifically. It is another to have deep insight and beautiful prose. Augustine had it all. He truly had a remarkable gift.

Augustine’s broad appeal finds him being favorably cited by a number of non-Christian authors and thinkers. For example, one author leads into a discussion of busyness among executives by quoting approvingly from Augustine.11 Carl Jung’s writings were influenced by Augustine,12 and Oscar Wilde didn’t think any of the early Christian writers were worth reading, except Augustine.13

Augustine: Background and Life

Augustine was born in AD 354 in Thagaste (North Africa, modern-day Algeria). His birthplace was solidly Christian by the time of his birth.

His mother, Monica, probably age twenty-three when he was born,14 was a committed Christian. His father, Patricius, was not. He grew up in a family that certainly was not wealthy, but we wouldn’t call them impoverished.15 He had at least one brother, Navigius, and maybe two sisters.

His mother, Monica, probably age twenty-three when he was born,14 was a committed Christian. His father, Patricius, was not. He grew up in a family that certainly was not wealthy, but we wouldn’t call them impoverished.15 He had at least one brother, Navigius, and maybe two sisters.

16Augustine struggled to make sense of the world. You can hear it in his reflections, “What, Lord, do I wish to say except that I do not know whence I came to be in this mortal life or, as I may call it, this living death?”

17One issue that haunted him was the existence of evil. The Manichean sect18 (started by an individual named Mani) attracted him; in their company he pursued an answer to the question of how a good God could allow evil and suffering. Eventually Augustine found the philosophy empty and unintelligible.

19Some have stated that Manicheanism “made fewer demands morally than Christianity.”20 It seems that various groups held different standards. Augustine was part of a more lax group. Other Manicheans were supposedly committed to a lifestyle of self-denial; Augustine later found out that many of these were not as pious as he originally thought.

21Next in his pilgrimage, Augustine found the ideas of Plato helpful in making sense of the world. Those rediscovering Plato, commonly called neo-Platonists,22 helped address what Augustine saw as some of the weaknesses in Manicheanism. For example, he came to reject the Manichean notion that God was “bounded by human form.”23 And yet Augustine found philosophical and personal problems with Neoplatonism. For the latter, there is no answer for the power and guilt of sin. When the philosophy or way of life that one adheres to is not workable in the real world, it tends to get one’s attention.

Neoplatonic thought did offer a bridge of sorts in demonstrating the reasonable nature of Christianity, but the most significant influence was a godly and learned bishop.

Neoplatonic thought did offer a bridge of sorts in demonstrating the reasonable nature of Christianity, but the most significant influence was a godly and learned bishop.

It is instructive to see how God used a certain individual in Augustine’s life quest for truth. Augustine eventually came into contact with Bishop Ambrose. Unlike the Manichean teacher Faustus — supposedly a great thinker but whom Augustine found quite unimpressive intellectually — the learned Ambrose had very satisfying answers to Augustine’s many questions.

If anyone is ever tempted to question how practical education is, one need only remember the impact of this formative relationship.

In embracing Christianity, Augustine finally found the truth that he so desperately desired. Unlike the neo-Platonic thinker Plotinus, who “so despised matter that he would not even mention his conception, birthday, or parents,” Augustine “gloried in the miraculous, once-for-all historical birth of Jesus the Messiah.”

24We ought to thank God for Ambrose, as it is his eloquence and learning that helped to lift Augustine out of the mire of manmade philosophies and make Christianity sound forth with clarity and conviction. Augustine’s conversion leads to his eventual appointment as bishop of Hippo (North Africa), where he serves for thirty-four years. Being a bishop in Africa was not that big of a deal, as there were almost seven hundred of them at the time.25 New ones were added weekly. However, as we shall soon see, Augustine would distinguish himself by his writing26 and leadership.

Keep in mind that Augustine lived during the era of the fall of the Western Roman Empire. His book The City of God was written specifically to address that shocking reality. We probably can’t overemphasize the far-reaching implications of this event; an event that many scholars believe has significant parallels to the moral decline of America today. David Wells, distinguished senior research professor at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary stated:

Would it be correct to surmise that in some ways Rome was not so much defeated by outsiders as by its own hand? And, if this surmise has any validity at all, should we not view our own deeply destructive social pathologies and the rotting of our national character with some alarm? America seems so strong, so invincible as it bestrides the world, its technology unmatched, its economic system robust and virile, its government stable, and the validity of its laws uncontested. Rome, however, once occupied a comparable position in the ancient world, and against every human calculation and expectation, it fell. Indeed, when the barbarians arrived outside the gates of Rome … they found no one at home. They simply walked into the city and began their conquest. A fate as improbable as this is not beyond repetition, even for America, if this nation cannot address its own disintegrating life, for no civilization will endure forever.27

John Piper’s equally sobering words should give us pause: “On August 26, 410,28 the unthinkable happened. After 900 years of impenetrable security, Rome was sacked by the Gothic army led by Alaric. St. Jerome, the translator of the Latin Vulgate, was in Palestine at the time and wrote, "If Rome can perish, what can be safe?"

John Piper’s equally sobering words should give us pause: “On August 26, 410,28 the unthinkable happened. After 900 years of impenetrable security, Rome was sacked by the Gothic army led by Alaric. St. Jerome, the translator of the Latin Vulgate, was in Palestine at the time and wrote, "If Rome can perish, what can be safe?"

29Most chilling may be the words of renowned historian Bryan Ward-Perkins, an avowed materialist:

The end of the Roman West witnessed horrors and dislocation of a kind I seriously hope never to have to live through; and it destroyed a complex civilization, throwing the inhabitants of the West back to a standard of living typical of prehistorical times. Romans before the fall were as certain as we are today that their world would continue forever substantially unchanged. They were wrong. We should be wise not to repeat their complacency.

30Though some parallels may be found between ancient Rome and modern-day America with respect to sobering signs of decline, we must be careful in making a seamless connection. Historian Victor Davis Hanson offers sage counsel,

But for any valid comparison, some basic ground rules of this old game of America as Rome are to be followed … keep in mind that the idea of a monolithic ”Rome” is a sort of construct — reflecting 700 years of Italian republican government, followed by another half-millennium of imperial Mediterranean rule. What “Rome” then do we of infant nations evoke? Is Rome to be the rather small agrarian republic trying to stop Carthage in the first Punic war? Or Edward Gibbon’s second-century AD hundred years of bliss? Or the chaos of a perennially tottering empire yet another two hundred years later?

31Augustine died at age seventy-five or six, in AD 430, the same year the Vandals started to lay siege to his own city of Hippo.

Why Should We Read The City of God?

I’ve taught on Augustine for many years. Reading his books has always paid big dividends.

When Christians ask me, “what one book do you wish every Christian would read?” I cheat a bit and say it would be a tie between Confessions by Augustine and The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan.

With all the love I have for Augustine’s Confessions, it might sound strange that I did not read The City of God until I was in my forties. If you have seen The City of God, you probably can guess why. It’s long! More than 400,000 words long. Let’s put that in perspective. “According to Amazon’s great Text Stats feature, the median length for all books is about 64,000 words.”32 We could say The City of God is like many books wrapped between two covers posing as one book!

There are many good reasons why one ought to read (and I would add reflectively read) The City of God. Here are three:

First, The City of God is well known for giving a brilliant response to prove that Christians were not responsible for the fall of Rome. How Augustine makes this case offers a compelling model for Christians today.

Augustine showcases the two related commandments of Jesus in Matthew 10:16 to be both “shrewd as serpents and innocent as doves.” We need exemplars who can help us here, and there are few better at doing so than Augustine. I’ve asked many Christians if they have ever heard a whole sermon on how to be both “shrewd and innocent” as Jesus commands. To this point, I’ve not received any affirmative answers. I also like to ask what word immediately comes to mind when people think of “shrewd.” All the synonyms are negative. Words like underhanded, unscrupulous, conniving, deceitful, and corrupt are given. Augustine shows us that the commandments of Jesus can be fully kept, even in our world that gladly resides east of Eden.

Second, Augustine’s strategy for reaching unbelievers desperately needs to be recovered. In his brilliant book Engaging Unbelief, Curtis Chang shows why Augustine’s approach in The City of God (and the same sort of strategy was employed by Aquinas in Summa Contra Gentiles) is so persuasive. Augustine would first learn the alternative stories to Christianity better than most of those who held those views.

Second, Augustine’s strategy for reaching unbelievers desperately needs to be recovered. In his brilliant book Engaging Unbelief, Curtis Chang shows why Augustine’s approach in The City of God (and the same sort of strategy was employed by Aquinas in Summa Contra Gentiles) is so persuasive. Augustine would first learn the alternative stories to Christianity better than most of those who held those views.

In other words, Augustine had a more sophisticated understanding of Roman gods than most of those who believed in these gods. As a result, Augustine had credibility to show how these gods could never deliver what people longed for, and how only the incarnation of Jesus would bring lasting satisfaction. This is very far afield from the all too common posture many Christians have today. Too many Christians, even those involved in apologetic types of ministry, have a proclivity to what I call a “penchant to pounce.”

Instead of seeking to make a thorough study of the alternative arguments to Christianity, too many are posed to offer glib and superficial responses. Augustine teaches us to first do our homework with all diligence before responding. Keep in mind that The City of God was written to respond to a friend’s request for how to respond to criticism against the Christian faith. Augustine took many years to get back to his friend, again highlighting how much he wanted to offer a fair and comprehensive response.

Last, love is a hallmark of Augustine’s writing. There is much to learn from Augustine on the all-important commandment to love God with all that we are and all that we have. Indeed, the two-city motif in The City of God is predicated on the only two people who will ever exist: those who love themselves and those who love God. Augustine’s pilgrimage to love God first and foremost piques our curiosity. It captures our attention because Augustine is brutally honest. Augustine understood the lure of various idols and false gods. This gives The City of God a credibility and relevance that is hard to beat. Our popular treatments on Christian growth with their beloved steps and strategies have much to learn from Augustine’s penetrating approach.

How to Read The City of God

My minor in seminary was church history, so it was high time I tackled Augustine’s behemoth, but how?

In a typical year, I will carefully read forty to sixty books. These include lots of underlining and marginalia. Hundreds of other books will receive a quick look, but my favorite reading is aided by a red pencil and black pen. The former is used for highlighting while the latter is for marginal notes.

To be an engaged and thoughtful reader, you want to get physical with your books. Get the kind of pens and pencils that will motivate you to take notes. If you are one of those unhappy types who think it is sacrilegious to write in books, then buy the kind of paper that will motivate you to write — a lot.

No matter how brilliant your memory, you will want to have some system for retrieving what you have read. C.S. Lewis wrote in books. During some teaching at Wheaton, I got to see the copy Lewis marked up of Paradise Lost. It was full of marginalia in his meticulous penmanship!

By a rather unscientific count, I figured The City of God has about 440,000 words. To keep from being overwhelmed, I kept telling myself I was not reading one book, but about seven. Since The City of God is like reading seven regular-sized books, it gave me greater patience as I plodded through the massive work. As it turned out, I took about a year to read it.

My other forty to sixty careful reads also continued that year. In fact, these other books were nice breaks from the demands Augustine’s masterpiece placed on me. These demands were not wholly negative. In fact, these demands were largely positive.

It’s simply that The City of God has so much to offer the attentive reader. You want to go slowly so as to absorb much of what is there. Absorbing everything on the first read is impossible. It is why classics like The City of God are reread with great profit. Take note here: Spurgeon, a voracious reader, read The Pilgrim’s Progress one hundred times! As Lewis liked to say, you have not read a book until you’ve reread it.

Some Suggestions and Further Motivation

*Great books such as The City of God are worth a hundred mediocre books. Actually, that is an understatement because mediocre books are ephemeral. They make little lasting difference. Remember The Prayer of Jabez? It sold ten million copies. I knew businessmen who were taking it in their briefcases, but no one talks about it anymore. In contrast to it, many continue to wrestle with the brilliance and far-reaching implications of The City of God.

*Great books such as The City of God are worth a hundred mediocre books. Actually, that is an understatement because mediocre books are ephemeral. They make little lasting difference. Remember The Prayer of Jabez? It sold ten million copies. I knew businessmen who were taking it in their briefcases, but no one talks about it anymore. In contrast to it, many continue to wrestle with the brilliance and far-reaching implications of The City of God.

*Consider reading The City of God with a friend. It will keep you both accountable, plus you will get the benefit of someone else’s insight.

*Whether you apply the previous suggestion or not, share with others what you are learning. It will solidify what you are reading and bless them.

*Remember to think turtle not hare in your reading. In that spirit, journalist Rod Dreher describes how he read Dante’s Divine Comedy:

Read slowly. A fast reader can get through the entire Commedia in a couple of weeks. But why would you want to do that? This is a book that needs to be taken slowly and savored. I spent six months with the Commedia the first time I read it … most of the cantos invite contemplation and self-reflection. There is no need to rush.33

*Keep spiritual formation as the ultimate goal in your reading. You are reading to be informed to be sure, but that is not the end of the road. Chew and consider sections that hit you. Confess your sins and be encouraged.

*A note to perfectionists: Years ago, a woman took a theology class I was teaching. She said the introductory book I recommended was beyond her. She described that she only understood about seventy percent of it. I said she now knew much more than she did previously!

*Avail yourself of various tools. Terry Miethe has written a wonderful commentary on Augustine’s big book.34 Professor James J. O’Donnell also provides some terrific tools available via the Internet.

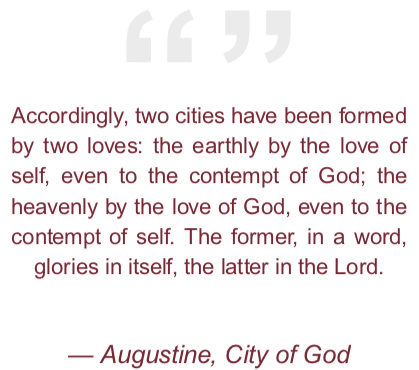

35Above all, Augustine would remind us that any endeavor, including reading, is only worthwhile if it makes us love God and people more:

Accordingly, two cities have been formed by two loves: the earthly by the love of self, even to the contempt of God; the heavenly by the love of God, even to the contempt of self. The former, in a word, glories in itself, the latter in the Lord. For the one seeks glory from men; but the greatest glory of the other is God, the witness of conscience. The one lifts up its head in its own glory; the other says to its God, “Thou art my glory, and the lifter up of mine head.” In the one, the princes and the nations it subdues are ruled by the love of ruling; in the other, the princes and the subjects serve one another in love, the latter obeying, while the former take thought for all. (The City of God, 14.28)

There’s no greater motivation to reading carefully than that!

|

Notes:

|

David George Moore

AuthorDavid George Moore, Author, lives in Austin, Texas and ministers through Two Cities Ministries. He holds degrees from Arizona State University, Dallas Theological Seminary, and Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. His authored several books including The Last Men’s Book You’ll Ever Need. Dave is a regular contributor to Patheos/Jesus Creed. His interview show can be found at www.mooreengaging.com.

Recommended Reading:

Michael Reeves, Theologians You Should Know: An Introduction: From the Apostolic Fathers to the 21st Century (Crossway, 2016)

Whether you realize it or not, you are the beneficiary of centuries of careful study and reflection on God's Word. The writings and teachings of figures from the past are crucial to what the church believes today. But just like intriguing guests of honor at a dinner party, these theologians can be intimidating to get to know.

Introducing you to the lives and thought of figures such as the Apostolic Fathers, Justin Martyr, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Martin Luther, John Calvin, Karl Barth, and others, this book makes the writings of these significant theologians accessible and approachable ― opening up for you the riches of church history and enlarging your vision of God and his plan for the world.

Augustine, City of God, translated by Henry Bettenson, (Penguin Classics, 2003)

St Augustine, bishop of Hippo, was one of the central figures in the history of Christianity, and City of God is one of his greatest theological works. Written as an eloquent defense of the faith at a time when the Roman Empire was on the brink of collapse, it examines the ancient pagan religions of Rome, the arguments of the Greek philosophers and the revelations of the Bible. Pointing the way forward to a citizenship that transcends the best political experiences of the world and offers citizenship that will last for eternity, City of God is one of the most influential documents in the development of Christianity.

Article — Justin Taylor, A Reading Plan for Augustine’s ‘The City of God’

In this article available on the The Gospel Coalition website, Justin Taylor observes that “(o)ne of the reasons that Augustine’s work [The City of God] remains unread today is because of its length and digressions.” Taylor notes that “(i)n lieu of an abridged version, Michael Haykin of Southern Seminary offers a selective reading guide to the book”, and includes it at the end of the article “for those who want to take up one of the great classics of the Christian tradition.”

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Philosophy and Influence

by David George Moore on July 26, 2024Ralph Waldo Emerson was a gifted nineteenth century...Read More

-

The Side B Stories – Nate Sala’s Story

by Jana Harmon, Nate Sala on July 19, 2024

-

Terrorism Through the Eyes of Faith

by Dennis Hollinger on July 12, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Hasn’t Science Proven That Belief in God Is an Outdated Superstition?

by Sharon Dirckx on July 1, 2024Many assume that scientific practice and belief in...Read More

-

Has the Bible Been Corrupted as Some Muslims Claim?

by Andy Bannister on June 1, 2024

-

Seeing Jesus Through the Eyes of Women

by Rebecca McLaughlin on May 15, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

22194

C.S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man Live Online Small Group 8:00 PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=c-s-lewiss-the-abolition-of-man-study-course&event_date=2024-10-02®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-10-02

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

C.S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man Live Online Small Group 8:00 PM ET

On October 2, 2024 at 8:00 pmSpeakers

David George Moore

Author

Team Members

David George Moore

AuthorDavid George Moore, Author, lives in Austin, Texas and ministers through Two Cities Ministries. He holds degrees from Arizona State University, Dallas Theological Seminary, and Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. His authored several books including The Last Men’s Book You’ll Ever Need. Dave is a regular contributor to Patheos/Jesus Creed. His interview show can be found at www.mooreengaging.com.