Back to series

“A Constant Stream”

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

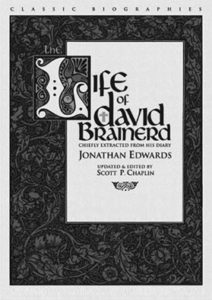

David Brainerd died on October 9, 1747, in Jonathan Edwards’s home in Northampton, Massachusetts. In what Edwards saw as a singular act of God’s providence, Brainerd had been persuaded by friends not to destroy his diary. Instead, he had put it in Edwards’s hands to dispose of as “would be most for God’s glory and the interest of religion.”

Jonathan Edwards edited the diary, added his own comments, and published it in 1749. Later editions also contained Brainerd’s missionary journal.

According to Marcus Loane:

The diary is a remarkable record of the interior life of the soul, and its entries still throb with the tremendous earnestness of a man whose heart was aflame for God. The journal is an objective history of the missionary work of twelve months, and its details are an astonishing testimony to the grace of God . . . Each needs to be studied as the revelation of a Christian character as rare as it was real.1

David Brainerd was born on April 20, 1718, at Haddam, Connecticut. As a young man, he had, as he says, “a very good outside.” After a time of “distressed, bewildered, and tumultuous state of mind” and rebellion against God’s law and sovereignty, the twenty-year-old Brainerd was radically transformed by a new vision of God’s glory: “My soul was so captivated and delighted with the excellence, loveliness, greatness… of God that I had no thought… at first, about my own salvation, and scarce reflected that there was such a creature as myself.”

In September 1739, Brainerd entered Yale College to prepare for the ministry. During Brainerd’s second year at Yale, George Whitefield visited the college, and a few months later so did Gilbert Tennent. Because of the strong revival preaching of these ministers, Brainerd, writes Jonathan Edwards, experienced “much of God’s gracious presence, and of the lively actings of true grace” but also was influenced by that “intemperate, indiscreet zeal, which was at that time too prevalent.” When Brainerd criticized one of the college tutors and the rector for their opposition to the revival, he was expelled. Neither his own apology nor Jonathan Edwards’s appeal moved the college authorities to allow Brainerd to complete his studies and graduate.

In the spring of 1742, Brainerd was overwhelmed by a strong desire that God use him in the work of missions “to the heathen.” His missionary commitment is expressed in his words: “Here I am, Lord, send me; send me to the ends of the earth; send me to the rough, the savage pagans of the wilderness; send me from all that is called comfort on earth; send me even to death itself, if it be but in thy service, and to promote thy kingdom.”

David Brainerd was licensed as a preacher of the gospel on July 29, 1742, and called by a Scottish missionary society to become their missionary to the Mahican Indians at Kaunaumeek in western Massachusetts. After twelve grueling months of ministry in this “farther-most edge of civilized America,” Brainerd, at the instruction of the mission board, changed his field to serve the Indians at the Forks of the Delaware in Pennsylvania.

David Brainerd was licensed as a preacher of the gospel on July 29, 1742, and called by a Scottish missionary society to become their missionary to the Mahican Indians at Kaunaumeek in western Massachusetts. After twelve grueling months of ministry in this “farther-most edge of civilized America,” Brainerd, at the instruction of the mission board, changed his field to serve the Indians at the Forks of the Delaware in Pennsylvania.

There he struggled with the intricate dialects of the Indian language, physical weariness and illness, and deep distrust on the part of the Indians, who had so often suffered at the hands of white men. Few of the Indians responded to his Christian message. He wrote: “To an eye of reason everything respecting the conversion of the heathen is as dark as midnight; yet I cannot but hope in God for the accomplishment of something glorious among them.”

In the summer of 1745, Brainerd moved to New Jersey to preach to the Delaware Indians at Crossweeksung near Freehold. A sudden and sovereign outpouring of God’s Spirit brought surprising success to Brainerd’s mission, leading to seventy-seven baptisms in less than a year.

Brainerd’s sick body, weakened by inadequate food and stricken with tuberculosis, began to fight its last battle. In May 1746 the Delaware Indians moved to Cranberry, New Jersey, where Brainerd hoped God would settle them “as a Christian congregation.” A final missionary trip to the Susquehanna in August 1746 was interrupted by illness, and Brainerd returned home to Cranberry, doubting that he would recover but “little exercised with melancholy, as in former seasons of weakness.” He continued to work and preach, sometimes from his bed, rejoicing that life and death did not depend upon his choice.

In November 1746 Brainerd left for New England but was forced by sickness to remain for the winter in Elizabethtown, in the home of Jonathan Dickinson, the first president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton). It is claimed by some that the college was founded by the Presbyterians because Brainerd was expelled from Yale for his support of the revival! In March 1747 Brainerd returned to Cranberry, where he visited his congregation of Indians for the last time. On March 18 he wrote: “About ten o’clock, I called my people together; and after having explained and sung a psalm, I prayed with them. There was a considerable degree of affection among them; I doubt not, in some instances, that which was more than merely natural.”

Too ill to resume his missionary work, David Brainerd set out again for New England and reached Jonathan Edwards’s home in Northampton, Massachusetts, on May 28, 1747. Edwards carefully records the final days of Brainerd’s life, noting such things as the last time he attended public worship and the last time he offered the family prayer. According to George Marsden, Edwards found “Brainerd’s prayers in the family stunning. Even his prayers returning thanks for food were awe inspiring.”

Edwards’s daughter Jerusha gave herself to the task of caring for the dying young missionary. There is no real evidence that they were engaged, but the story of David Brainerd and Jerusha Edwards, writes Marsden, is “one of the history’s fabled spiritual love tales.”2

Brainerd corrected some of his private writings, wrote letters, and gave spiritual counsel to those about him. “He spoke to some of my younger children,” writes Edwards, “one by one.” When someone came into his room with a Bible, Brainerd said, “Oh that dear book: that lovely book! I shall soon see it opened: the mysteries that are in it, and the mysteries of God’s providence, will all be unfolded.”

Bidding his friends good-bye, especially his beloved Jerusha, and assuring her that “we shall spend a happy eternity together,” David Brainerd died on October 9, 1747, at the age of twenty-nine. His soul, writes Jonathan Edwards, “as we may well conclude, was received by his dear Lord and Master, as an eminently faithful servant, into that state of perfection and fruition of God, which he had so often and so ardently longed for; and was welcomed by the glorious assembly in the upper world, as one peculiarly fitted to join them in their blessed employments and enjoyments.”

A few months later, on Sunday, February 14, Jerusha died. The grief-stricken father, who said that Jerusha was “generally esteemed the flower of the family,” preached her funeral sermon on the poignant words from Job—“Youth is like a flower that is cut down.” She was seventeen years old. Her body was buried next to Brainerd’s in the Northampton Cemetery.

A few months later, on Sunday, February 14, Jerusha died. The grief-stricken father, who said that Jerusha was “generally esteemed the flower of the family,” preached her funeral sermon on the poignant words from Job—“Youth is like a flower that is cut down.” She was seventeen years old. Her body was buried next to Brainerd’s in the Northampton Cemetery.

David Brainerd’s brief life was consumed by two great passions. On February 4, 1744, he wrote in his diary: “Sanctification in myself, and the ingathering of God’s elect, was all my desire; and the hope of its accomplishment, all my joy.”

Edwards’s Life of David Brainerd begins with a classic sentence: “There are two ways of representing and recommending true religion and virtue to the world… the one is by doctrine and precept, the other is by instance and example.” Edwards had already dealt with the matter of true and false religion theologically in The Distinguishing Marks of the Work of the Spirit of God (1741) and The Treatise Concerning Religious Affections (1746). In 1749 he published Brainerd’s Life as “a remarkable instance of true and eminent piety, in heart and practice.”

Every page of Brainerd’s diary is filled with expressions of longing for holiness. On January 1, 1746, he wrote: “O that I might live nearer to God this year than I did the last… May I for the future be enabled more sensibly to make the glory of God my all.” Brainerd attempted to “live to God in every capacity of life.” He prayed: “May I never loiter in my heavenly journey.”

One can find shortcomings in Brainerd’s life. Edwards notes a tendency to melancholy, which Brainerd himself found to be “a great hindrance to spiritual fervency.” Edwards also faults Brainerd for “being excessive in his labours, not taking due care of his strength.” Understandably, Brainerd struggled with loneliness. He knew that solitude aggravated his trials but it was better, he thought, than to be “incumbered with noise and tumult.” There is little or no appreciation for the beauties of God’s creation in Brainerd’s diary, unlike Edwards, who saw images of God’s glory and excellence everywhere. Edwards, however, found the young man who was dying in his home “remarkably sociable, pleasant and entertaining in his conversation; yet solid, savoury, spiritual and very profitable; appearing meek, modest and humble, far from any stiffness, moroseness, superstitious demureness, or affected singularity in speech or behaviour.”

Jonathan Edwards believed that Brainerd’s life “shows the right way to success in the work of the ministry,” and “his example of labouring, praying, denying himself, and enduring hardness, with unfainting resolution and patience, and his faithful, vigilant, and prudent conduct in many other respects… may afford instruction to missionaries in particular.” The last words of Brainerd’s diary sum up his missionary passion: “May this blessed work… prevail among the poor Indians here as well as spread elsewhere till their remotest tribes shall see the salvation of God! Amen.”

David Brainerd’s faith was steady rather than flashy. It was not, writes Edwards, “like a land-flood, which flows far and wide and with a rapid stream bearing down all before it, and then dried up; but more like a stream fed by living springs; which though sometimes increased by showers, and at other times diminished by drought, yet is a constant stream.”

Brainerd’s influence grew remarkably within the transatlantic evangelical community through The Life of David Brainerd, Edwards’s most frequently reprinted and widely read book. It was the first American biography to reach a large European audience. It became the best-selling religious book in nineteenth-century America (with more than thirty different editions) and remains in print to the present day.

John Wesley prepared an abridged version of Edwards’s book and recommended it with the words: “Let every preacher read carefully over The Life of David Brainerd. Let us be followers of him, as he was of Christ, in absolute self-devotion, in total deadness to the world, and in fervent love to God and man.”

John Wesley prepared an abridged version of Edwards’s book and recommended it with the words: “Let every preacher read carefully over The Life of David Brainerd. Let us be followers of him, as he was of Christ, in absolute self-devotion, in total deadness to the world, and in fervent love to God and man.”

In 1769 John Newton wrote: “Next to the Word of God, I like those books best which give an account of the lives and experiences of His people… No book of this kind has been more welcome to me than the life of Mr. Brainerd of New England.”

Brainerd’s missionary career spanned less than five years, but Edwards’s Life of David Brainerd revealed a missionary hero whose impact was astounding. The little book made a significant contribution to the new era of missions that sent British and American Christians to many parts of the world.

Archibald Alexander said that a missionary spirit was enkindled in the New Side Presbyterian Church as a result of the publication of Brainerd’s diary.

As William Carey prepared to go to India, Brainerd’s Life was “almost a second Bible.” When Carey, Ward, and Marshman signed the historic agreement that laid down the principles of their missionary work at Serampore, they agreed to “often look at Brainerd in the woods of America, pouring out his very soul before God for the perishing heathen without whose salvation nothing could make him happy.”

Robert Murray McCheyne was deeply moved when he first read Brainerd’s Life in 1832. He remarked that as a result of Brainerd’s example he was “more set upon missionary enterprise than ever.” A few years later McCheyne wrote in a letter: “O to have Brainerd’s heart for perfect holiness.”

In the preface to an 1851 reprint of The Life of David Brainerd, Horatius Bonar warned against taking Brainerd’s life as a perfect life and points out some few defects, but goes on to hold up his life as a protest “against the easy-minded religion of our day.” If Brainerd’s life, Bonar stated, is used to quicken our consciences and urge us forward in the “same path of high attainment,” we will find it “an unspeakable blessing.” The example of Brainerd’s “life of marvelous nearness to… God, which he lived during his brief day on earth,” continues to inspire Christians, Bonar wrote. “His life was not a great life, as men use the word,” Bonar concluded, but it was “a life of one plan, expending itself in the fulfillment of one great aim, and in the doing of one great deed—serving God.”

Two hundred and fifty years after Brainerd’s death, The Life of David Brainerd still challenges and inspires readers.

Two hundred and fifty years after Brainerd’s death, The Life of David Brainerd still challenges and inspires readers.

Oswald J. Smith, founding pastor of the People’s Church in Toronto, paid tribute to Brainerd with these words:

So greatly was I influenced by the life of David Brainerd in the early years of my ministry that I named my youngest son after him. When I was but eighteen years of age, I found myself 3,000 miles from home, a missionary to the Indians. No wonder I love Brainerd! Brainerd it was who taught me to fast and pray. I learned that greater things could be wrought by daily contact with God than by preaching. When I feel myself growing cold I turn to Brainerd and he always warms my heart. No man ever had a greater passion for souls. To live wholly for God was his one great aim and ambition.3

A few years ago, John Piper wrote:

I thank God for the ministry of David Brainerd in my own life—the passion for prayer, the spiritual feast of fasting, the sweetness of the Word of God, the unremitting perseverance through hardship, the relentless focus on the glory of God, the utter dependence on grace, the final resting in the righteousness of Christ, the pursuit of perishing sinners, the holiness while suffering, the fixing the mind on what is eternal, and finishing well without cursing the disease that cut him down at twenty-nine.4

The “constant stream” still flows.

| There have been many editions of Brainerd’s diary. The Life of David Brainerd, edited by Norman Pettit, appeared in 1985, as volume 7 in The Works of Jonathan Edwards, (Yale University Press). Books by Marcus Loane, Oswald J. Smith, and John Piper cited in the following notes contain helpful short chapters on David Brainerd.

Notes

|

David B. Calhoun

ProfessorDavid B. Calhoun, (1937-2021) was Professor Emeritus of Church History at Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri. A minister of the Presbyterian Church in America, he has taught at Covenant College, Columbia Bible College (now Columbia International University), and Jamaica Bible College (where he was also principal). Calhoun has served with Ministries in Action in the West Indies and in Europe and as dean of the Iona Centres for Theological Study. He was a board member (and for some years president) of Presbyterian Mission International, a mission board that assists nationals who are Covenant Seminary graduates to return to their homelands for ministry.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Philosophy and Influence

by David George Moore on July 26, 2024Ralph Waldo Emerson was a gifted nineteenth century...Read More

-

The Side B Stories – Nate Sala’s Story

by Jana Harmon, Nate Sala on July 19, 2024

-

Terrorism Through the Eyes of Faith

by Dennis Hollinger on July 12, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Hasn’t Science Proven That Belief in God Is an Outdated Superstition?

by Sharon Dirckx on July 1, 2024Many assume that scientific practice and belief in...Read More

-

Has the Bible Been Corrupted as Some Muslims Claim?

by Andy Bannister on June 1, 2024

-

Seeing Jesus Through the Eyes of Women

by Rebecca McLaughlin on May 15, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

22194

C.S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man Live Online Small Group 8:00 PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=c-s-lewiss-the-abolition-of-man-study-course&event_date=2024-10-02®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-10-02

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

C.S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man Live Online Small Group 8:00 PM ET

On October 2, 2024 at 8:00 pmSpeakers

David B. Calhoun

Professor

Team Members

David B. Calhoun

ProfessorDavid B. Calhoun, (1937-2021) was Professor Emeritus of Church History at Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri. A minister of the Presbyterian Church in America, he has taught at Covenant College, Columbia Bible College (now Columbia International University), and Jamaica Bible College (where he was also principal). Calhoun has served with Ministries in Action in the West Indies and in Europe and as dean of the Iona Centres for Theological Study. He was a board member (and for some years president) of Presbyterian Mission International, a mission board that assists nationals who are Covenant Seminary graduates to return to their homelands for ministry.