Back to series

Good Books, Bad Books

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

Bad books always lie. They lie most of all about the human condition.” The very idea offended her, and she wanted to talk.

And so on a cold winter evening in the Poconos, I sat down with a Princeton University Ph.D. candidate who had joined several dozen graduate students for a weekend of reflection. Drawing from Cornell, Columbia, Rutgers, and Princeton, they were described to me in this way: “These are bright students, and they love God—but they typically don’t know how to connect what they believe with their studies. Can you help?”

As I pondered how to approach the weekend, Walker Percy’s insight about literature and life—that “bad books always lie…”—came to mind, and I thought that I would start the weekend off with a discussion of his argument. The thesis is true beyond the world of novels, echoing into every area of study, every arena of human existence. Bad economic visions always lie. They lie most of all about the human condition. And the same is true for politics and painting, for biology and sociology—all across the curriculum it is the view of the human condition which sets the terms of the debate. What we believe about who we are—our origin, nature, and destiny—affects everything else.

She and I sat down for what turned out to be a three-hour conversation. Several years into her work, the focus of her study was early modern Japanese literature, Buddhist literature, she explained. And she was offended at Percy’s argument, where he moves from “Bad books always lie….” to asking, tongue-incheek and yet with the deepest seriousness, “Have you read any good Marxist novels lately? Any good behaviorist novels lately? Any good Freudian novels lately? Any good Buddhist novels lately?” And with each worldview, he points out why it fails to provide the necessary grist for a good story. Audaciously, given the pluralizing and secularizing character of contemporary life, he then says that novels are dependent upon the Jewish and Christian view of human nature and history.

She and I sat down for what turned out to be a three-hour conversation. Several years into her work, the focus of her study was early modern Japanese literature, Buddhist literature, she explained. And she was offended at Percy’s argument, where he moves from “Bad books always lie….” to asking, tongue-incheek and yet with the deepest seriousness, “Have you read any good Marxist novels lately? Any good behaviorist novels lately? Any good Freudian novels lately? Any good Buddhist novels lately?” And with each worldview, he points out why it fails to provide the necessary grist for a good story. Audaciously, given the pluralizing and secularizing character of contemporary life, he then says that novels are dependent upon the Jewish and Christian view of human nature and history.

Simply said, Percy saw the issues as a line in the sand: either one worked out of the Jewish and Christian tradition, with its narrative-shaped understanding of the human condition, or one did not have what was required for a good story. In his own words, “JudeoChristianity is about pilgrims who have something wrong with them and are embarked on a search to find a way out. This is also what novels are about.”

For the first half hour she was mad, at me and at Percy. I listened, and asked several questions. She became less angry, and then, much to my surprise, said, “You know, the Buddhist literature isn’t very interesting to read… in the end, it’s always the same story. This life means nothing. There is no point to anything we say or do.” She looked me straight in the eye and said, “But I can’t say that to my professors or my peers. I wouldn’t be allowed to finish my degree. I have to find a way to celebrate this ‘important voice’ in global literature; that’s what I’m supposed to do…. but it’s not very much fun.”

On Stories

What is it about stories? Why are we as human beings so drawn to good ones? And so disappointed with bad ones? One of my first memories is, as a young boy, putting my pencil and paper aside during a sermon whenever the pastor would begin to tell a story. Something changed in the very air of the sanctuary, it seemed to my little ears.

I love good stories—whether they come in books, films, songs, or poems. When I was nine, ten, and eleven years old, I lived in biographies. I suppose the librarians loved me, because I came in week after week, wanting more to read. At age twelve I discovered the stories of Ralph Moody, an autobiographical series which followed the life of a young boy in a Colorado ranching family. As a native of the Colorado mountains myself, and the grandson of a cattleman who invited me into his life summer after summer, these tales of family, horses, cows, choices, and consequences shaped my sixth-grade life.

Years later stories continue to form my understanding of myself, and my understanding of the world around me. And though I still read Moody’s books to my children, my own reading is more Dickens and Dostoevsky. It is true of me what C.S. Lewis said of himself: “You can’t get a cup of tea large enough or a book long enough to suit me.” There is something about the way we are made—something about being created in the image of God and created with imaginations that can be awakened by grace to the truth about ourselves and the world—that loves a good story.

But like all of God’s gifts, even stories can be skewed; we can miss the point, making too much, or too little, of their meaning. Rather than being meaningful, because they take their rightful place in God’s world, they become meaningless. Think of the Princeton graduate student and her Buddhist literature.

To press the point: in the movement from modern to post-modern, in leaving behind the certainties of the Cartesian universe with its too neat-and-clean dichotomy between facts and values, everything becomes a story. It is a “narrative vision of this” or a “narrative understanding of that.” One’s perspective—read “story”—on reality becomes more important than reality. But of course that is where the rub is. The post-modern world grants no access to reality, to truth, to the way the world really is; all we are only allowed is “my story,” which means an individual’s particular perspective and viewpoint. The Princeton student was asked to celebrate the Buddhist “story” about life and the world—whether it was a meaningful one or not, whether it satisfied deeply human aspirations for coherence and dignity or not. The “story” is the point. Period.

The history of the world of ideas is one of pendulum shifts, and this is its most recent expression. The Enlightenment insisted that what we know is either “objective fact” or “subjective value”—and of course it prized most of all what is “objective” because the “impersonal” character of facts is trustworthy and true for everyone everywhere. Or so it was argued. In effect it canceled out the more profoundly human ways of making sense of one’s place in the universe; it ruled “out of order” more biblically rooted ways of knowing, where confidence about truth is possible without being dependent upon the scientific method to prove it so.

How do we weigh faith, hope, and love? Can we quantify responsibility? One of Walker Percy’s characters, Tom More—a fictional descendent of Sir Thomas More, “the man for all seasons”—creates “the quantitative-qualitative ontological lapso-meter.” And just what does a lapso-meter do? It measures lapses, of course… in the human soul. Percy is smiling here.

In contrast, the post-Enlightenment writers—hanging onto the pendulum as they do so—insist that everything is “personal,” by which they mean one’s own private, subjective perspective. Nietzsche saw into this moment, over a century ago, observing—even as he joined the atheists in their celebration—that when God goes, so does any possibility of continuing to talk about meaning and morality. He said that we would limp on through the 20th century “on the mere pittance” of the old decaying God-based moral codes. But then, in the 21st would come a period more dreadful than the great wars of the 20th century, a time of “the total eclipse of all values.” Epistemologies do have ethical implications.

The Theology of a Good Story

There are writers who see the problem of the Enlightenment, but do not fall into the abyss of the nihilism for Everyman which post-modernism too often means. Walker Percy is one of the best. But there are others— two of my favorites are C. S. Lewis and Wendell Berry—who stand in a long line of writers whose moral imaginations were shaped by the truths of the Christian

vision of God and his world, writers who offered history a way of understanding the world that is really there, without being of the world.

What does that world look like? Several years ago I was asked by an Anglican bishop to help develop a curriculum for “the young theologians” of his diocese; in particular he wanted to give them tools to think theologically about the culture. One of the many books we drew upon was Lesslie Newbigin’s The Gospel in a Pluralist Society.

I still remember the chills that ran down my spine the first time I read his account of a conversation with a Hindu scholar, a man who became his close friend over the 40 years Newbigin spent in India as a missionary. The Hindu said to him, wonderingly,

Why is it that Christian missionaries have told us, ‘Read our sacred text, too. Add it to your supply.’ Now I have

read your Bible, and it seems to me a completely unique book. Its view of history, a story with a beginning and an

end which makes universal claims, as well as its view of the human person as a responsible actor in history, make

this different than any other book I have read.

The words still ring in my heart. The Hindu saw more clearly than most Christians. Immersed in a Hindu understanding of history and human nature, he could see the stark contrast set forth in the story of the Christian Scriptures. No, not another book to add to his supply, at all! Rather it was a book with a completely unique story, and its implications rippled out into the

universe.

Some truths are true, anytime and anywhere. It does not matter whether one lives in the pre-modern, modern, or what we call post-modern era; whether one lives in the East or the West. They are ideas which are true, they reflect the reality of the way things really are. In his own effort to break through the language problem in a culture moving from modern to post-modern—people using words to mean anything and everything— Francis Schaeffer called these ideas “true truths,” and saw them as the contours of the biblical vision of reality, of human life in space and time.

The Hindu was right, profoundly so. The Bible is a story, a story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation. In Stanley Hauerwas’ image, the Church is “a story-formed community”; we understand ourselves in relation to God, each other, and the world, by the ideas and images of the biblical narrative. How else do we make sense of the theology embedded in the unfolding story of God’s work over time, spanning centuries and cultures? It is a story of human beings making their way in a world where the choices are real, and therefore where there are consequences—for blessing and for curse.

Think about David’s sorry and shameful stumble. Called by God “a man after my own heart,” David uses his political position to steal another man’s wife and puts her husband in mortal danger, somehow imagining that he can find true happiness in flaunting the commandments of God. From the text, it seems that it was at least several years before David was able to see himself truthfully. How could that be? Psalm 51 offers us a window into his heart, but David’s repentant cry only comes after he sees himself in a story told by the prophet Nathan.

Angry, moved to judgment by the injustice of Nathan’s account of a powerful man abusing a powerless man, David rises from his throne—only to meet the finger of Nathan, the prophet of God, saying to him: You are the man!

The moral universe implicit on every page of the Old Testament is brought into the New as God, incarnate in the person of a Palestinian rabbi, reveals himself to those with ears to hear. Most of his teaching is given in parables, like the story of the two houses which are in truth a story of two hearts, at the conclusion of what we call “the sermon on the mount.” In setting after setting, conversation after conversation, Jesus chooses to tell stories as the means of offering the truths of the kingdom.

The moral universe implicit on every page of the Old Testament is brought into the New as God, incarnate in the person of a Palestinian rabbi, reveals himself to those with ears to hear. Most of his teaching is given in parables, like the story of the two houses which are in truth a story of two hearts, at the conclusion of what we call “the sermon on the mount.” In setting after setting, conversation after conversation, Jesus chooses to tell stories as the means of offering the truths of the kingdom.

Take the story which we call “the good Samaritan.” It grew out of questions asked and answered between an expert in the law and Jesus. The expert wanted to “test” Jesus, Luke writes, and therefore his question was not altogether honest. Jesus knew that, and asked him a question as a means of answering. They went back and forth, and finally the expert decided he would rather retreat into an academic conversation. In our terms, he tried to deconstruct the word “neighbor,” to abstract it from life. Knowing his heart, Jesus told him a parable.

When the short story was over, Jesus asked another question: So, who was the neighbor? One more time, the expert in the law gave the right answer; that was not his problem. And Jesus told him, “Go, apprentice yourself to the Samaritan.” In Percy’s imagery, this is the parable of the man who got all A’s but was flunking life.

This is not an isolated incident in the pedagogy of Jesus. Time and again, confronted by people who knew the outlines of biblical faith but whose hearts were not open to the truth about God and themselves, Jesus chose to tell a story.

Good Books and the Human Condition

Good stories tell the truth about the human condition. That is the divine brilliance in Nathan’s prophetic tale and in the parables of Jesus. Bad books, on the other hand, distort the story about human nature and history—and Princeton graduate students and the rest of us do not find them compelling.

If the coming summer nights find you wanting a larger cup of tea and a longer book, then allow me to suggest some wonderful stories. They will probe the hidden places of the heart—if you have ears to hear. That of course is the mystery of the moral dynamism of the human heart, and the deeper reality: good story or not, truth is always for those with ears to hear.

One of the very best is one of our oldest, The Quest of the Holy Grail. Written as a guide to Christian discipleship in the 13th century, the tales of Lancelot, Gawain, and Percival are full of true temptation and true grace. It is a culture-wide loss that most of us know more about the Quest from Monty Python and Indiana Jones than we do from this morally rich story.

Every night that the play, Les Miserables, is done on the stages of London’s West End or New York’s Broadway, the gospel goes out. But as great as that production is, it pales in comparison to the richness of Victor Hugo’s novel. For example, where we get a few minutes to ponder the bishop’s remarkable gift of grace to Jean Valjean on stage, the book offers us 50 pages, telling the story of the formation of the bishop’s soul, why his open door is a true reflection of his open heart. And of course its uncanny echo of Jesus’ parable of the prodigal son makes it even more extraordinary.

The trilogy by Sigrid Undset, Kristen Lavransdatter, is a favorite among my friends. It seems that whoever reads these stories of medieval Scandinavia, deeply wrought as they are from a Christian consciousness, falls in love with them—not because they are happy, in a cheap sense; in fact they are full of disappointment and sorrow. It is more because they are so true; we see ourselves, the secrets of our hearts, the vanities which skew our own true happiness. But when all is said and done, they are stories of great grace.

And finally, Wendell Berry’s stories of “the Port William membership,” the community of family and friends over a century who populate his novels and short stories, have become companions to me and to mine. With unusual skill, he writes of griefs and graces that only make sense if God is there; a meaning and morality that are marked by love are at the heart of his literary universe. His stories, like the best stories, are always for those with ears to hear.

Stories—good stories—have a way of finding their way into the deepest places. Shakespeare understood this very well. Generations later we continue to see ourselves in his plays; the comedies, the tragedies, the tales of glory and shame, young and old alike find a world that is strangely familiar. At heart, Hamlet’s observation so many seasons ago, is still true: “The play’s the thing to catch the conscience of the king!” Still true, that is, for those with ears to hear.

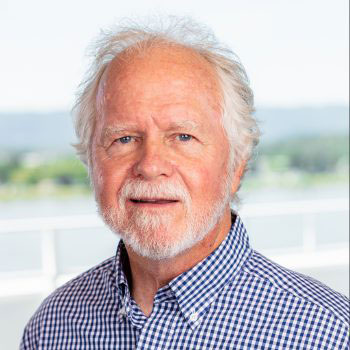

Steven Garber

ProfessorSteven Garber is the Senior Fellow for Vocation and the Common Good for the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust. As a teacher, he has recently served as Professor of Marketplace Theology and Director of the Masters in Leadership, Theology and Society at Regent College, Vancouver, BC. he is the author of several books, including Visions of Vocation: Common Grace for the Common Good, his most recent is The Seamless Life: A Tapestry of Love and Learning, Worship and Work. One of the founders of the Wedgwood Circle, and has been a Principal of the Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation and Culture. He completed his PhD in the Philosophy of Learning at Pennsylvania State University.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

Fix Your Eyes Upon Jesus

by Steven Garber, Aimee Riegert on June 27, 2025Perhaps the most prominent and current figure who...Read More

-

An Honest Search for God – Dr. Jay Medenwaldt’s Story

by Jana Harmon, Jay Medenwaldt on June 20, 2025

-

Moving Beyond Forgiveness to an Abundant Life

by Robert Saucy, Aimee Riegert on June 13, 2025

-

Recent Publications

Are Miracles Possible

by Christopher L. Reese on June 1, 2025The 21st century has provoked many conversations and...Read More

-

Is God Just, Not Fair?

by Jennifer Rothschild on May 15, 2025

-

Seeking Dietrich Bonhoeffer

by Joseph A. Kohm on April 29, 2025

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

24720

The Adventure of Joining God in His Work Live Online Small Group 7:00 PM CT

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=the-adventure-of-joining-god-in-his-work-live-online-small-group-700-pm-ct&event_date=2025-09-16®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2025-09-16

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

The Adventure of Joining God in His Work Live Online Small Group 7:00 PM CT

On September 16, 2025 at 7:00 pmSpeakers

Steven Garber

Professor

Team Members

Steven Garber

ProfessorSteven Garber is the Senior Fellow for Vocation and the Common Good for the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust. As a teacher, he has recently served as Professor of Marketplace Theology and Director of the Masters in Leadership, Theology and Society at Regent College, Vancouver, BC. he is the author of several books, including Visions of Vocation: Common Grace for the Common Good, his most recent is The Seamless Life: A Tapestry of Love and Learning, Worship and Work. One of the founders of the Wedgwood Circle, and has been a Principal of the Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation and Culture. He completed his PhD in the Philosophy of Learning at Pennsylvania State University.