Back to series

Nuggets of Wisdom

VOLUME 5 NUMBER 2 ISSUE OF BROADCAST TALKS (PDF)

BROADCAST TALKS presents ideas to cultivate Christ-like thinking and living. Each issue features a transcription of a talk presented at an event of The C. S. Lewis Institute. The following is adapted from an interview with John Lennox, conducted by Joel Woodruff, President of the C.S. Lewis Institute, at McLean Presbyterian Church, McLean, Virginia, on May 17, 2019. The event was entitled Can Science Explain Everything?

Q: It would be nice to learn a little bit more about your life’s journey. I know that you studied at some of the world’s greatest higher-education institutions, such as Cambridge University, and you’ve been a professor at Oxford. Would it be safe to assume that you came from a privileged, highly educated background and family? Is that right?

No, it’s not right. My parents were quite humble people in educational terms. My father was not allowed to go to university because his father insisted that he run a family business in a country town employing, I suppose, thirty to forty people, selling all kinds of household things, like carpets and clothing, and so on. But he longed to have an education, and, in a sense, he taught himself. And in another sense, he was living his life through me. My mum was a teacher of typewriting and that kind of thing in a middle school. One of the things she did for all her children was that she taught them to touch-type before they left home, and that has been very useful. In that sense they were humble people.

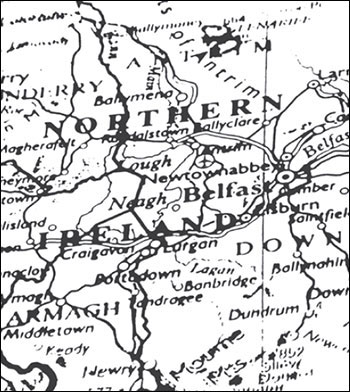

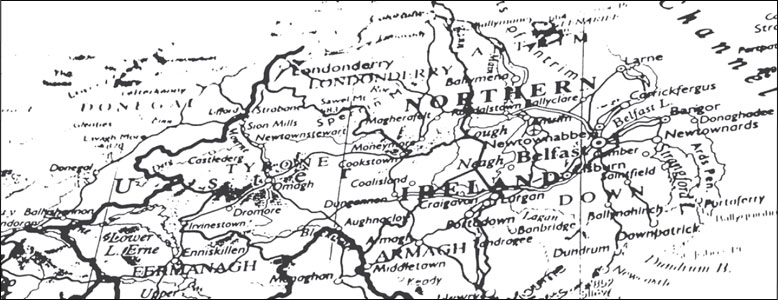

But they were very impressive Christians. And I’d say two things about that. My home country, Northern Ireland, is sadly famous for its sectarianism and violence because of historical problems, sociological problems, and the tension is often described as being between Protestants and Catholics. But my father was convinced that every man and woman, no matter what they believed, was made in the image of God and therefore of infinite value. He decided he’d express that by employing as equally as he could across the divide. That meant bombs. It meant that my brother nearly lost his life when a glass window blew into his face and took his face essentially right off, and it had to be stitched back on. And that impressed me and left me with the sense that as I go out into life, I need to fix that in my mind: that the people I meet have dignity no matter where they’re from, no matter what they do, no matter what their wealth is of any kind — intellectual, financial, and so on — because they’re made in the image of God. That was very important and still is to me today.

But they were very impressive Christians. And I’d say two things about that. My home country, Northern Ireland, is sadly famous for its sectarianism and violence because of historical problems, sociological problems, and the tension is often described as being between Protestants and Catholics. But my father was convinced that every man and woman, no matter what they believed, was made in the image of God and therefore of infinite value. He decided he’d express that by employing as equally as he could across the divide. That meant bombs. It meant that my brother nearly lost his life when a glass window blew into his face and took his face essentially right off, and it had to be stitched back on. And that impressed me and left me with the sense that as I go out into life, I need to fix that in my mind: that the people I meet have dignity no matter where they’re from, no matter what they do, no matter what their wealth is of any kind — intellectual, financial, and so on — because they’re made in the image of God. That was very important and still is to me today.

The second thing is, they loved me enough to give me space to think. That was rare. Because in a small country, often, the expressions of Christianity become ghetto-like, rigid, legalistic, and my parents weren’t like that. I think so often that many of my contemporaries, the moment they got away from home, their Christianity disappeared overnight because it was never real; it was never personal; it was never theirs. But they’d allowed me this space and encouraged me to think and ask questions and read other worldviews. Now think of a father like that who gives his son at the age of thirteen a copy of the Communist Manifesto. I said, “What’s that, Dad?” He said, “It’s the Communist Manifesto. Have you read it?” “No, why should I read it?” “Because you need to know what other people think.”

And it was that kind of instruction that really began my intellectual development very early. And then he discovered C.S. Lewis. And he responded to Lewis’s books, Mere Christianity in particular. He used to keep twenty of them in the glove compartment in his car because in those days it was quite safe to pick up hitchhikers, and many a hitchhiker left happy with a copy of Mere Christianity. But Dad was bright enough apart from the education that he hadn’t had, to realize this was gold dust. So he shared it with me, and I devoured it because I discovered an intellectual guide. But, more than that, because my background was Christian, and impressively Christian, I still have no idea what it’s like to be an adult and an atheist or agnostic. And Lewis became for me a mentor, showing me the inside of his intellectual life, what it actually feels like to be an atheist, and therefore he has accompanied me, so to speak, up to this day. And of course it didn’t hurt that he came from Northern Ireland as well.

Q: In your professional career, you went into mathematics and science. When, as a child or an adolescent, did you discover that math and science was something you enjoyed? How did that process come about?

I think these things often have a great deal to do with teachers. I had a primary teacher and I used to ask her, because I found arithmetic astonishingly easy, “Please, give me some more homework.” I was the only child ever to have done that. Because of that, she took a bit of an interest in me, and that stayed, although I wobbled all over the place because once I discovered foreign languages, I was gripped by grammar. Now that may not rejoice your hearts very much, but you see there’s a logic to it all. Mathematics is a language, pure mathematics. It’s highly compressed and highly precise. Natural languages, some of them are much more structured than others; Latin was the one I got to first. And because I studied its grammar and loved its grammar, I learned how English worked, because we don’t have such a structured grammar. Here it was that I began to read C.S. Lewis’s books on the English language, and they have been of crucial importance to my intellectual development and in my work in explaining the Christian faith; just understanding how your own language works.

Those were formative things. I discovered languages, and then I became a ham radio operator. My father bought me a shortwave radio. And of course I immediately heard private individuals talking with shortwave. And my curiosity (I was twelve or thirteen) was such that I found out that they were amateur radio operators. So I said, “How do I become one?” And I set the exam and built a transmitter and soon I was on the airwaves. And this was spectacular! We didn’t have the money to travel. Foreign travel was very rare. But I could travel on the radio! I could speak French to people in Martinique or France or Switzerland.

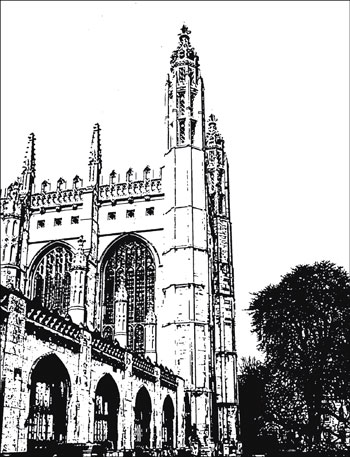

Then, because I got interested in radio, I thought, I know what I want to be — an electronics engineer! So I applied and got a scholarship for Queens University, Belfast. It was a very good scholarship, and the headmaster came to me one day and said, “Lennox, would you be interested in going to Cambridge?” He’d been there, and he said, “We don’t have people who can teach you physics and chemistry to that level, but I can teach you mathematics.” So I consulted a person who became a mentor and lifelong friend and guide to Bible teaching and also things intellectual. And he said to my father, “If you can give him the chance, do.” That was the big change in my life. I got a scholarship to go to Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

Q: So you left Northern Ireland for the University of Cambridge. I imagine that was a different world to enter. What are some of the highlights of your university years and in leaving Northern Ireland to go to the big world of Cambridge?

It was a big world, but it was an interesting world. Of course I didn’t know that I was well prepared for it, having read Lewis and many other books and some fairly heavy books like Alfred North Whitehead’s philosophy, and all this kind of thing. I had a friend who was two or three years older and already at university; our idea of a holiday was to try to borrow a school car and fill the trunk of it with books and then go and read them and discuss them. So I was in a way remarkably prepared for university. I decided from day one that if Christianity’s true, I am not going to hide my light. That proved very interesting because there was a Christian group that made a presentation on the first week, and I felt their logic was a bit faulty, so I challenged it publicly. There were quite a few atheists and agnostics who came, and they rather liked me for doing that. So I immediately hit the ground running, so to speak, and in one sense I’ve been running ever since. I very rapidly decided that what I hadn’t gained at home was any real personal knowledge of what makes people atheists, agnostics, proponents of other religions. So I decided to search out people who did not share my Christian worldview and befriend them. And I’ve been doing that for nearly fifty-five or fifty-six years. I’ve proved that it is really the key to get to know people. I do it like Socrates said — my great intellectual hero — by asking people questions and listening to what they say, because you never know what’s going on in our culture unless you listen. Some of us, especially from Ireland, are great talkers, but somebody once taught me that I’ve got one mouth and two ears and to use them in that proportion might be wise.

It was a big world, but it was an interesting world. Of course I didn’t know that I was well prepared for it, having read Lewis and many other books and some fairly heavy books like Alfred North Whitehead’s philosophy, and all this kind of thing. I had a friend who was two or three years older and already at university; our idea of a holiday was to try to borrow a school car and fill the trunk of it with books and then go and read them and discuss them. So I was in a way remarkably prepared for university. I decided from day one that if Christianity’s true, I am not going to hide my light. That proved very interesting because there was a Christian group that made a presentation on the first week, and I felt their logic was a bit faulty, so I challenged it publicly. There were quite a few atheists and agnostics who came, and they rather liked me for doing that. So I immediately hit the ground running, so to speak, and in one sense I’ve been running ever since. I very rapidly decided that what I hadn’t gained at home was any real personal knowledge of what makes people atheists, agnostics, proponents of other religions. So I decided to search out people who did not share my Christian worldview and befriend them. And I’ve been doing that for nearly fifty-five or fifty-six years. I’ve proved that it is really the key to get to know people. I do it like Socrates said — my great intellectual hero — by asking people questions and listening to what they say, because you never know what’s going on in our culture unless you listen. Some of us, especially from Ireland, are great talkers, but somebody once taught me that I’ve got one mouth and two ears and to use them in that proportion might be wise.

Q: While you were at Cambridge I understand that you actually got to hear C.S. Lewis speak. Is that right?

I did indeed. I went there in 1962. We start in October, and it was very cold. I didn’t know Lewis was seriously ill. But he had volunteered a series of eight lectures in the Christmas term in 1962, and I discovered that he gave the lectures just across the road from the Mathematics Institute. So I would sneak out from time to time and went to hear Lewis. And that was such a memory, you know. Would you like to hear what it was like to listen to Lewis? You would?

Well, it was cold, and Lewis was a big chap, even bigger than me, and he would burst through the double doors; he’d start lecturing the moment he came in the door. He had on a hat and a scarf and a coat — the place was packed of course because he was a legend at that time. He would wend his way through the students and gradually divest himself of his outer garments. By the time he got to the lectern, you’d had five minutes of a brilliant lecture. He lectured scintillating stuff. What I heard were his final lectures on John Donne, the English poet. He’d come to the end, fifty-four minutes or something, and then he’d reverse the process. So he didn’t stop lecturing. He’d put on his hat, he kept lecturing; he wound up his scarf, he put on his heavy coat, and his last words were uttered exactly as he burst out through the door. No Q&A!

Q: Wonderful story. If you could name three people who have most influenced your life, who would those three people be?

You mean people outside Scripture? Yes, well my parents, clearly. The man who advised me to go to Cambridge is a professor, David Gooding. His books are not known as they should be but they’re brilliant; you can download them for free on a website called Myrtlefield House [https://www.myrtlefieldhouse.com]. If you’re a pastor or a teacher in a church, they are goldmine stuff, because he, like Lewis, understood how literature works and he applied his knowledge of literature, Greek and Latin literature, to the study of Scripture. The result is breathtaking, and that’s not an exaggeration. He’s in his nineties now and unfortunately suffering from dementia, but he took me under his wing; for one year of my undergraduate time at Cambridge, he was doing a sabbatical at Tyndale House. I often say to people — I’ve had a public scientific education and a private classical education, and that has meant that I feel equally at home, in a way, among the sciences or the humanities. I’m passionate about literature, language, and history particularly, but not only those. Those have enriched me enormously, especially foreign literature, but not only. He taught me, really, most of what I know about Scripture and how to handle arguments. It just was a phenomenal resource; I often say if I see anything it’s only because a child standing on the shoulders of its parents sees a lot further than the parent. We stand on large shoulders. So he influenced me. I suppose Lewis would have to be the other person, through his writings. But of course I’ve read thousands of books and there are all kinds of people, but if you want to narrow it down, that’s it. I should of course mention my wife, because she’s stuck with me for more than fifty years. I met her on my first day at Cambridge. My mentor said, in almost biblical language — it’s very funny looking back — he said, “My boy, in Cambridge there is a man with four daughters.” So I turned up at church on Sunday morning and there they were, four blonde girls, sort of descending from the tallest to the smallest. So I grabbed the tallest. And I couldn’t have done anything [without her]. Why am I sitting here, and she’s not here [with me]? Because she said, “You must do this.” Through life, she’s been a support. You cannot do these things, folks, unless you’ve got full, unhesitating support of your life’s partner; I’m so thankful that I was given someone who cared for the children and who looked after our home through thick and thin when I was in very dangerous situations behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War era. So I want to pay a very special tribute to Sally.

Q: What is the role of the Christian in academia?

The role of a Christian in academia is to be a Christian in academia. That means knowing how to put your head above the parapet. That’s true not only in academia but in the professions. We live in a politically correct generation where there’s a great deal of fear. I understand it. I’ve had pressure put on me, and my heart goes out to academics, professional people, who are so terrified at being excluded by their colleagues that they’ve gone silent. There are many silent Christians in the West, I fear. They go to church. They say their prayers. They read their Bibles. But it’s years since they witnessed to anybody. It’s not that they don’t believe Christianity is true. It’s that they’re scared to say it’s true. I’d love to go into this in detail because it’s very close to my heart, so close that I’ve just written a little book about it called Have No Fear. It’s the cheapest book you’ll find on Amazon, especially if you buy a hundred of them to give away!

Have no fear! Because fear and shame are paralyzing people. Now, I’m not talking at you, because I don’t know anybody, except liars, who don’t get scared. We all have a level of fear, and battling the fear of beginning to put our head cautiously above the parapet, and we have to be wise as serpents and harmless as doves. It applies to all of us, not just academics. But academics come in for a lot of flak these days in the Western world, tragically. We’ve built up universities to protect freedom of speech and ideas, and some of them are now becoming hotbeds of political correctness and non-platforming and stopping people from spreading rational ideas for discussion. That’s appalling, and it’s inhibiting human development and flourishing and freedom of speech, and it will destroy society at the end if it goes on at the rate that it’s going. That’s a huge topic.

Q: Why is it that you are a Christian? Why do you choose to follow Jesus Christ?

The primary reason is that I believe Christianity is true. The first evidence for that was seeing it living in my parents. So I tested it from an early age. I could see it was resilient; it supported something. The other reasons came pouring in later. The great thing about Christianity is that it is testable. Jesus claims that if we trust Him and repent of the mess we’ve made of our lives and others and trust Him for salvation, we will receive peace with God. I meet many people with no peace at all. They would love to get peace. We will receive forgiveness. How much anguish there is, even in this room, as the result of lack of forgiveness. I put it this way often: You meet somebody; you don’t know them; and you see they’re in a terrible state. Perhaps a student is suicidal, narcotic-dependent, all this kind of thing. You meet them six months later, and they’ve got a smile on their face and they’re no longer dependent on narcotics. You say, What’s happened? And they say something like this: Well, I became a Christian. Or, I met Jesus. Or, I got converted. There are many ways of saying it. When you see that, as I have, endless times, you begin to mathematically add two and two and get four. There’s a connection between transformed lives and faith in Christ as Savior and Lord. That is the hard test. People often say to me, You’re a scientist; you believe in testing theories; you can’t test Christianity. I say that’s absolute nonsense! One of my main reasons for being a Christian is that I’ve tested it and it works. The proof of the pudding is always in the eating. Let me put it this way: God is not a theory. He’s a person. And when we’re thinking about these things, there is a danger on the intellectual side which is very important: that we’re relating to a theory. Do I believe this theory or not? But we’ve got to rise above that. This theory is important, but relating to a person has got many dimensions other than relating to a theory; you know that if you’re married and so on. Persons are much more complex than theories. The thrilling thing is that having been made in the image of God, we are capable through Christ of having a real relationship with Him. In the end, that is the supreme test.

The primary reason is that I believe Christianity is true. The first evidence for that was seeing it living in my parents. So I tested it from an early age. I could see it was resilient; it supported something. The other reasons came pouring in later. The great thing about Christianity is that it is testable. Jesus claims that if we trust Him and repent of the mess we’ve made of our lives and others and trust Him for salvation, we will receive peace with God. I meet many people with no peace at all. They would love to get peace. We will receive forgiveness. How much anguish there is, even in this room, as the result of lack of forgiveness. I put it this way often: You meet somebody; you don’t know them; and you see they’re in a terrible state. Perhaps a student is suicidal, narcotic-dependent, all this kind of thing. You meet them six months later, and they’ve got a smile on their face and they’re no longer dependent on narcotics. You say, What’s happened? And they say something like this: Well, I became a Christian. Or, I met Jesus. Or, I got converted. There are many ways of saying it. When you see that, as I have, endless times, you begin to mathematically add two and two and get four. There’s a connection between transformed lives and faith in Christ as Savior and Lord. That is the hard test. People often say to me, You’re a scientist; you believe in testing theories; you can’t test Christianity. I say that’s absolute nonsense! One of my main reasons for being a Christian is that I’ve tested it and it works. The proof of the pudding is always in the eating. Let me put it this way: God is not a theory. He’s a person. And when we’re thinking about these things, there is a danger on the intellectual side which is very important: that we’re relating to a theory. Do I believe this theory or not? But we’ve got to rise above that. This theory is important, but relating to a person has got many dimensions other than relating to a theory; you know that if you’re married and so on. Persons are much more complex than theories. The thrilling thing is that having been made in the image of God, we are capable through Christ of having a real relationship with Him. In the end, that is the supreme test.

Q: What final words of wisdom would you leave for your children and grandchildren?

Not only to my children but to anybody. Our lives rush past. We’ve become fixated on digital equipment that’s robbing us of time. People say to me they’ve no time. They’ve loads of time. If you want to know how much time you’ve got, just ask yourself a simple question: How much time have I spent in the last week fiddling with a piece of digital equipment and doing things that have no relevance whatsoever to my profession or my life? Then say, Have I got any time? We’re robbing ourselves of the most important thing in life if we’re Christians, and that is seeking fellowship with God through His Word. You will never make any impact on this world by reading the Bible for five minutes before you jump into bed. I’m brutally practical. You husbands will never make any impact on the world if you’re not praying with your wives and leading your families spiritually. You just won’t. It’s not possible to develop a deep relationship within a family that is not triangular; that is, if it doesn’t include Jesus Christ in one corner. And we can seek to repent of these things and really begin to make time so that in that sense we get to know God.

I used to think that science and all of these arguments were much more interesting than the Bible, and I discussed it with my mentor, David Gooding, who said, “Would you like to do a Bible study?” and he invited me to do one. One night transformed my life, completely, in Cambridge. There for the very first time I met a person who took Scripture seriously. He pinned it up on a wall, and he entered a dialogue with Matthew. It was just mind-blowing how he began to open the treasures of Scripture. But it takes input and work. Many of you people are professionals. Think of the work you had to do to get to where you are. Now if God has given you that kind of mind, how much of it are you using on Him? What worries me silly is people who rise in their professional career but their knowledge of Scripture remains on a basic, baby, Sunday school level. So the moment their peers raise any questions, they instantly detect they’ve not thought it through. And that silences them, often forever, some of them.

So it’s a clarion call and I very much admire what Joel and his colleagues are doing. It’s a way of pushing against this tide of mediocrity where we don’t take God’s Word seriously. So what that tells me, when I find it in my own heart, is that I don’t really love God. All this talk about going to heaven and going to meet with Christ, if that happened to you now, what would you say to Him? What would you talk about? It is very serious stuff. C.S. Lewis says, “All the leaves of the New Testament rustle with an expectation of eternity.” And if we’ve never sensed that, the Word of God is given to us to make eternal things real, and we need to spend time immersed in it, prayerfully reading it, with other people and alone.

I had a very close friend at Cambridge. Years ago we agreed that, whoever died first, the other remaining person would preach at the funeral. He thought I would die first because I was quite a bit older. But I’ll never forget the day when he called me and with tears in his eyes he said, “I’ve got a tumor as big as a grapefruit, and that’s going to be it. You’ll have to take my funeral.”

I said to him, “What should I say?” Without hesitation he said, “Tell them to do what we did as students in Cambridge, to pore over the Word of God prayerfully and wait on God until His face appears. And then they will have something to say.”

Do you want something to say? Are you a pastor or a teacher at Sunday school? If you want something to say, there is no shortcut. I’ll never forget those essentially last words to the world, and I’ve repeated them many times. That was what transformed me. It wasn’t reading all the philosophy in the world, although I love it and find it interesting, and it’s a way of building bridges and dealing with difficulties, but in the end, unless God is real through His Word, we’re missing the central fellowship that He offers us.

[Video of the complete version of this interview, including Q&A, is available Here. Additional information related to the topic of the interview is included in John Lennox’s books Can Science Explain Everything? and Have No Fear: Being Salt and Light Even When It’s Costly.]

John Lennox

ProfessorDr. John C. Lennox is an Irish mathematician, bioethicist, and Christian apologist. Now retired, he is the Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford as well as the Emeritus Fellow in Mathematics and Philosophy of Science at Green Templeton College, Oxford. A former professor of mathematics and the philosophy of science, he has also been a part of public debates with New Atheists such as Richard Dawkins, presenting intellectual defenses of Christianity. Lennox has written acclaimed books such as Cosmic Chemistry: Do God and Science Mix and most recently 2084: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humanity. He received his Ph.D. of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge, while also holding numerous honorary degrees from other British universities.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

Making Sense of Science and Faith – Sharon’s Story

by Sharon Dirckx, Jana Harmon on September 13, 2024Dr. Sharon Dirckx was raised in a secular...Read More

-

Dismantling Atheism – Daniel’s Story

by Jana Harmon, Daniel on August 30, 2024

-

How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism

by Joseph Loconte on August 23, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Isn ’t Atheism Based on Scientific Fact Whereas Christianity is Based on “Faith”?

by Cameron McAllister on September 1, 2024I once led a dialogue at the University...Read More

-

A Christian Response to Anti-Semitism

by Darrell Bock, Randy Newman, Thomas A. Tarrants on August 15, 2024

-

What Scientific Proof Do We Have That There Is a God?

by Christopher L. Reese on August 1, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

22667

GLOBAL EVENT: Is God Just, Not Fair? with Jennifer Rothschild, 8:00PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=global-event-is-god-just-not-fair-with-jennifer-rothschild-800pm-et&event_date=2024-09-20®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-09-20

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

GLOBAL EVENT: Is God Just, Not Fair? with Jennifer Rothschild, 8:00PM ET

On September 20, 2024 at 8:00 pmCategories

Speakers

John Lennox

Professor

Team Members

John Lennox

ProfessorDr. John C. Lennox is an Irish mathematician, bioethicist, and Christian apologist. Now retired, he is the Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford as well as the Emeritus Fellow in Mathematics and Philosophy of Science at Green Templeton College, Oxford. A former professor of mathematics and the philosophy of science, he has also been a part of public debates with New Atheists such as Richard Dawkins, presenting intellectual defenses of Christianity. Lennox has written acclaimed books such as Cosmic Chemistry: Do God and Science Mix and most recently 2084: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humanity. He received his Ph.D. of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge, while also holding numerous honorary degrees from other British universities.