Back to series

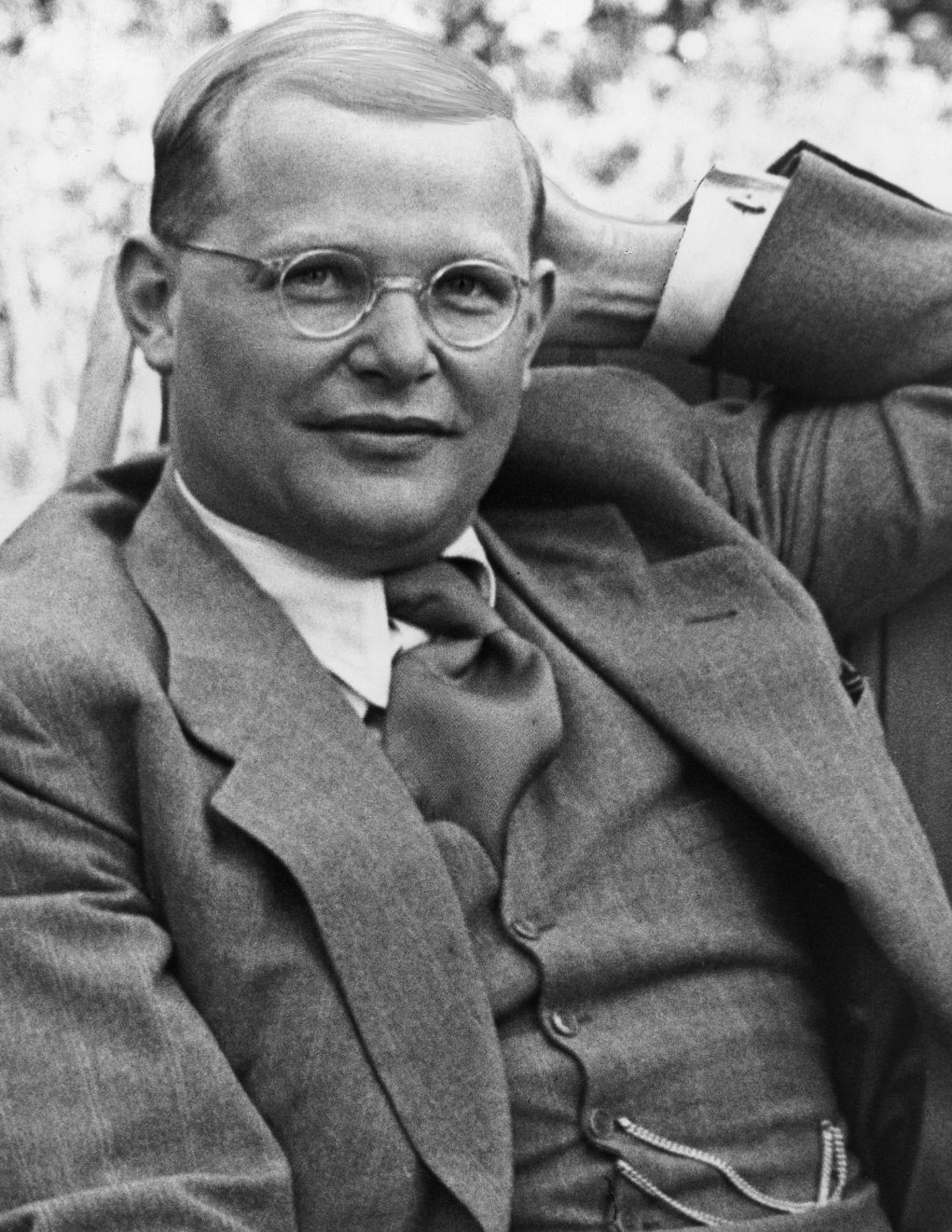

SEEKING DIETRICH BONHOEFFER

JOSEPH A. KOHM

VICE PRESIDENT FOR DEVELOPMENT,

C.S. LEWIS INSTITUTE AND CSLI CITY DIRECTOR – VIRGINIA BEACH

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

pril 9, 2025, marked the 80th anniversary of the death of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. This milestone, combined with the release of Angel Studios’ new film Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin. has led to a resurgence of interest in the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Not that interest in Bonhoeffer has ever really disappeared. His books, such as The Cost of Discipleship, continue to sell, and seminaries offer classes on his life and theology. But, like many historical figures, the Lutheran pastor martyred by the Nazis just a few weeks before the end of World War II has been co-opted by a variety of people and groups in recent years in attempts to give moral force and weight to certain ideological and partisan beliefs. They typically use contextomy, taking a quote, removing it from its surrounding context, and then stamping it on a cause to make it seem that Bonhoeffer would be marching with that cause. Instead of making Bonhoeffer more attractive to potential readers and students, it has created a confusing gauntlet that many may be afraid to navigate for fear of being associated with certain causes or political parties.

pril 9, 2025, marked the 80th anniversary of the death of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. This milestone, combined with the release of Angel Studios’ new film Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin. has led to a resurgence of interest in the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Not that interest in Bonhoeffer has ever really disappeared. His books, such as The Cost of Discipleship, continue to sell, and seminaries offer classes on his life and theology. But, like many historical figures, the Lutheran pastor martyred by the Nazis just a few weeks before the end of World War II has been co-opted by a variety of people and groups in recent years in attempts to give moral force and weight to certain ideological and partisan beliefs. They typically use contextomy, taking a quote, removing it from its surrounding context, and then stamping it on a cause to make it seem that Bonhoeffer would be marching with that cause. Instead of making Bonhoeffer more attractive to potential readers and students, it has created a confusing gauntlet that many may be afraid to navigate for fear of being associated with certain causes or political parties.

The antidote as applied to the study of Dietrich Bonhoeffer is to read Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Two-hundred-and-eighty-character social media posts or clever memes are poor substitutes for opening The Cost of Discipleship (having an open Bible next to your open copy of The Cost of Discipleship will enhance your Bonhoeffer experience even more!) and slowly and linearly progressing through his theological train of thought. A common refrain among those who study Bonhoeffer is that after reading just a few sentences, they need to put whatever they are reading down, be it one of his other seminal works, such as Life Together, Ethics, or Letters and Papers from Prison, for further contemplation.

Studying the life, thought, and writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer is a worthy endeavor. He shares a similarity with C.S. Lewis in that they both seem to be bottomless wells. No matter how many times I have picked up Bonhoeffer’s Ethics, I find something new, just as when I pick up Lewis’s Mere Christianity. But it is not merely Bonhoeffer’s theology and ideas that merit examination; it’s his life and his death, placed within the turbulent historical period in which he lived, that also provide us with instruction. It would be impossible to distill Dietrich Bonhoeffer down to just a few ideas, but contemplating his writings regarding ecclesiology, civil disobedience, cheap grace, and the relationship between faith and obedience—what I call Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s “Big Ideas”— might serve as a jumping-off point for those looking to begin to read and study him.

Born February 4, 1906, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was one of eight children in an affluent family of high achievers. His father, Karl Bonhoeffer, served as a professor of psychiatry at the University of Breslau until 1912 before moving to the University of Berlin. His mother, Paula, managed the home and was responsible for the early years of each Bonhoeffer child’s education. Dietrich’s oldest brother, Karl-Friedrich, was a physicist who succeeded in splitting the hydrogen atom. Another brother, Klaus, was a lawyer eventually murdered in a Nazi prison for his role in the resistance. Yet another brother, Walter, was killed fighting in World War I. Growing up cocooned in comfort and erudition, Dietrich surprised his family by announcing at age thirteen that he wanted to be a theologian. The Bonhoeffers did not attend church, and his father, Karl, could at best be described as an agnostic. However, Dietrich’s mother had a strong foundational Christian faith and made Bible study a regular part of the children’s moral education.

For his eighteenth birthday, Bonhoeffer wanted to spend time studying in Rome. This would be a formative period for him and would lay a foundation for the first of his “Big Ideas,” specifically, what or who constitutes the Christian Church. During his weeks spent in Rome, Bonhoeffer’s exposure to the grandeur and liturgy of the Catholic Church forced him to contrast what he called “the universality” of Catholicism with the “nationalistic” Protestantism of his native German Lutheranism. For the remainder of his life, he tried to resolve the tension between the Church being a pointer to God and the Church being a hindrance to Christian discipleship. Ultimately, Bonhoeffer’s ideas regarding the composition and purpose of the Church fused with his Christology, beginning with his 1927 doctoral dissertation, “A Dogmatic Inquiry into the Sociology of the Church,” where he wrote, “God becomes more tangible because Christ exists in this community in word, in sacrament, and in the mutual love of its members.”

After completing his studies, Bonhoeffer would spend the remainder of his life working within three primary vocation — pastor, academic, and parachurch leader. Just as the Nazis began their rise to power, Bonhoeffer was beginning his professional life along these three tracks. His experience in Rome and his view of the universality of the Catholic Church fostered in him a lifelong spirit of ecumenism, which led to his work with World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship Through Churches. The contacts he made with World Alliance would later prove valuable when he began his resistance work against the Nazis. Ordained in November 1931, his first appointment was as a chaplain to Technical University in Berlin. As an academic, Bonhoeffer began lecturing at the University of Berlin.

Out of his role as a pastor another of Bonhoeffer’s big ideas was born. One of these ideas, concerning the role civil disobedience plays for both the follower of Christ and the Church at large, is sourced in an essay written to a group of other pastors. Composed in April 1933 in response to a series of laws enacted to exclude nonAryans from working in churches, and titled “The Church and the Jewish Question,” Bonhoeffer posits three reactions the Church must have regarding the State. First, the Church must act as a form of conscience toward the State, asking the State “whether its actions are legitimate and in accordance with its character as state.” Second, the Church, “has an unconditional obligation” toward any victims resulting from any illegitimate State activity. And finally, when the Church, “sees the state fail in its function of creating law and order,” the Church must not only “bandage the victims under the wheel” of the State, but they are, “to jam a spoke in the wheel itself.” Unfortunately, Bonhoeffer doesn’t give us a bright line test for determining the appropriateness of jamming a spoke in the wheel, and it is here where people and groups representing a wide variety of ideological and political causes stake their claim to Bonhoeffer.

In 1935, Bonhoeffer was tabbed by the Confessing Church to operate an illegal and subversive seminary, first in the town of Zingst and later in the town of Finkenwalde, in an abandoned seminary along the Baltic coast of northern Germany. Formally called the Emergency Teaching Seminary, his first class consisted of twenty-some ordinands living together in community. Bonhoeffer chronicled his experience at Finkenwalde in his book Life Together. Perhaps the most important fruit to come out of his time at Finkenwalde was Bonhoeffer’s most popular work, The Cost of Discipleship. Originally titled Follow Me, it is the source for Bonhoeffer’s most well known big idea, cheap grace.

The very first sentence of the very first chapter of The Cost of Discipleship reads, “Cheap grace is the deadly enemy of the church.” Bonhoeffer defines cheap grace as “the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, Communion without confession, absolution without personal confession.” Cheap grace permits an easy flirtation with sin without the recognition that two thousand years ago there was a cost for that grace that God lavishes on us. Bonhoeffer emphasizes, “It cost God the life of his Son.” This intellectual overfamiliarity many believers have with God’s grace and forgiveness without acknowledging its cost leads to a fatal hardening of the heart and a cocooning of sinful habits, so that the “Christian life comes to mean nothing more than living in the world and as the world, in being no different from the world.”

Bonhoeffer’s corollary to cheap grace, also found within the pages of The Cost of Discipleship, is another of his big ideas. Instead of the absorption of worldliness via reliance on cheap grace, Bonhoeffer writes that, for the Christian, “The road to faith passes through obedience to the call of Jesus.” He argues that there is a symbiotic relationship between obedience and faith, and it is this: “Only he who believes is obedient, and only he who is obedient believes.” Obedience is rooted in faith, and without obedience to the commands of Christ, our faith will “be pious humbug.” Pastorally, Bonhoeffer would tell those who came to him for advice concerning a weakness of faith that they were likely struggling to be obedient; he would tell those who came to him struggling with obedience that they were likely struggling with faith.

This relationship between faith and obedience is not merely circular; it’s a spiral, and it is critical for our walk as followers of Christ. This upward spiral occurs in that when we obey God, our faith increases; when our faith increases, we obey God more, with faith and obedience increasing more and more like links in a chain leading us toward sanctification, more and more transformed into the image of Christ.

The Gestapo eventually closed Finkenwalde in September 1937, and just a few months later Bonhoeffer had his first interaction with the Nazi resistance through a meeting with his brother Klaus and brother-in-law Hans von Dohnanyi. This meeting ultimately led to his becoming a double agent with Germany’s intelligence branch, the Abwehr. The Germans thought they were getting a respected international theologian who would have access to church leaders across Europe and the UK, but Bonhoeffer was in fact relaying to these same church leaders efforts within Germany to topple Hitler. It was during this period that Bonhoeffer was working on his book Ethics, a sweeping collection of his ideas on topics such as the nature of the State and the Christian’s relationship to it, and, most importantly, a Christian’s role within it. In reading Ethics, one can sense the palpable shadow of Nazism hanging over Bonhoeffer’s words. He would continue writing Ethics even during his time in prison, and it would not be published until after his death.

Although it is doubtful that Bonhoeffer engaged in any affirmative actions that advanced any of the various plots to assassinate Hitler, he certainly had knowledge of them. He did have an active role in the planning and smuggling out of Germany and into Sweden fourteen Jews in September 1941. This was known as Operation 7. Several factors probably contributed to the Gestapo turning their suspicious gaze toward Bonhoeffer: (1) his close personal proximity to his brother-in-law Hans von Dohnanyi, who was very active in the Nazi resistance movement; (2) Bonhoeffer’s past public behavior toward the Nazis, when, as late as September 1940, Bonhoeffer was prohibited from speaking in public; and (3) loose ends in carrying out Operation 7 implicated several close to Bonhoeffer, which finally led to Bonhoeffer himself.

Bonhoeffer was taken into custody on April 4, 1943. He continued to be productive, working on Ethics, writing prayers, composing poetry, and corresponding with family members and best friend Eberhard Bethge, thanks to a sympathetic prison guard. Much of this material can be found in the book Letters and Papers from Prison. For Christmas in 1944, just a few months before his execution, he gifted his family a poem titled “From All Good Powers,” which begins,

By faithful, quiet powers of good surrounded

so wondrously consoled and sheltered here—

I wish to live these days with you in spirit

and with you enter a new year.

The old year still would try our hearts to torment,

of evil times we still do bear the weight;

salvation for which you did create.

And should you offer us the cup of suffering,

though heavy, brimming full and bitter brand,

we’ll thankfully accept it, never flinching,

from your good heart and your beloved hand.

Encapsulated in this final poem is the big idea that runs as a thread throughout all Bonhoeffer’s works. One might picture Bonhoeffer, much like Paul writing from a Roman prison, in the isolation and filth of a Nazi prison, telling his family that he is surrounded by “quiet powers of good” and that he longs to be with them again. Yet the evil times he finds himself in creates “torment” with the possibility that God may offer “the cup of suffering.” But the disciple of Christ must “thankfully accept it” knowing that somehow, it comes from God’s “beloved hand.”

So it is in our contemporary world. Though Western Christians are not living under Nazi oppression, no one gets through this life unscathed. We live in a world where people are diagnosed with cancer. We live in a world where people wrestle with debilitating anxiety and crippling loneliness. We live in a world where people battle addictions, depression, where they are consumed with anger, and where they mourn because they’ve lost loved ones. Yet like Bonhoeffer, we must recognize there is a delicate balance between the earthly and the eternal. God offers and often surrounds us with temporal good, such as the privilege of serving Him and the blessing of family and friends. But the consequence of living in a fallen world means that despite God’s “good heart’ and “beloved hand,” the disciple of Christ must thankfully accept suffering or the rise of evil, “never flinching,” as demonstrated by Bonhoeffer himself on his last earthly day.

On the morning of April 9, 1945, Bonhoeffer was led to a courtyard within the Flossenburg concentration camp. The camp physician that day described Bonhoeffer in his last moments, observing him “bow his knees and pray fervently to God,” while remaining “brave” and “composed” before finally stepping toward the gallows. In Bonhoeffer’s death, he doesn’t leave us with a last big idea. Instead, he leaves us with a question. In The Cost of Discipleship, he asks, “How can we live the Christian life in the modern world?” It’s a question each follower of Jesus must answer daily. The world, the flesh, and the devil will be happy to suggest answers for us leading to a watereddown, therapeutic, and ineffective faith. Those answers given by the world are a long way from the answer Dietrich Bonhoeffer provides in The Cost of Discipleship. Bonhoeffer’s answer to the question of how a Christian is to live in the modern world is this: “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” Bonhoeffer is not necessarily referring to physical death. Not every Christian is called to martyrdom. He is instead referring to the death of our lusts, our affections, our love of self. If all those were not enough, to live as a Christian in the modern world according to Bonhoeffer is to go even further — it is to suffer for the sake of Jesus Christ. He writes, “Suffering, then, is the badge of true discipleship.”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s big ideas, his life, and especially his death, transcend the trite and silly turf wars with those playing political or ideological tug-of-war with his legacy. The best way for followers of Jesus Christ to commemorate the 80th anniversary of his death is to read Dietrich Bonhoeffer and apply his “Big Ideas” to your life.

1

How familiar were you with the life and writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer before reading this article?

Have you read articles where he was quoted or heard him quoted in sermons?

Have you read any books by him or about him?

After reading the article, would you like to read one or more of Bonhoeffer’s books?

2

What do you think about the concept of “cheap grace”, as explained by Bonhoeffer?

Why does he view cheap grace as “the deadly enemy of the church”?

3

After considering the article, how would you explain the relationship between faith and obedience?

Why is it of critical importance?

Share your reflections on these questions with our team.

Joseph A. Kohm

Vice President for Development, CSLI & CSLI City Director, Virginia BeachJoseph A. Kohm, C.S. Lewis Institute Vice President for Development and City Director for Virginia Beach. Joe is an attorney and formerly worked as a Certified Major League Baseball Player Agent. He earned his Master’s in Management Science from the State University of New York at Oswego and both his J.D. and M.Div. from Regent University. Joe is the author of The Unknown Garden of Another’s Heart: The Surprising Friendship between C.S. Lewis and Arthur Greeves (Wipf and Stock, 2022.)

Recommended Reading:

Books by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

Doubting Naturalism – Dr. Michael Egnor’s story

by Jana Harmon, Michael R. Egnor on September 26, 2025Dr. Michael spent decades trusting science to answer...Read More

-

Mere Hermeneutics: Why do Christians Disagree on How to Interpret the Bible?

by Kathleen Noller, Kevin J. Vanhoozer on September 19, 2025

-

Profiles in Faith: Martin Luther

by Aimee Riegert, Arthur W. Lindsley on September 19, 2025

-

Recent Publications

What is the Christian response to transgenderism?

by Alycia Wood on August 25, 2025Many modern people believe the universe is governed...Read More

-

Cosmic Chemistry: Do God and Science Mix?

by John Lennox on August 15, 2025

-

When Truth Is Lost, Goodness Distorted, And Beauty Forgotten

by Thiago M. Silva on July 29, 2025

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

23993

Heart and Mind Discipleship Live Online Small Group 1:00 PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=heart-and-mind-discipleship-live-online-small-group-800-pm-et&event_date=2025-10-02®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2025-10-02

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

Heart and Mind Discipleship Live Online Small Group 1:00 PM ET

On October 2, 2025 at 1:00 pmCategories

Speakers

Joseph A. Kohm

Vice President for Development, CSLI & CSLI City Director, Virginia Beach

Team Members

Joseph A. Kohm

Vice President for Development, CSLI & CSLI City Director, Virginia BeachJoseph A. Kohm, C.S. Lewis Institute Vice President for Development and City Director for Virginia Beach. Joe is an attorney and formerly worked as a Certified Major League Baseball Player Agent. He earned his Master’s in Management Science from the State University of New York at Oswego and both his J.D. and M.Div. from Regent University. Joe is the author of The Unknown Garden of Another’s Heart: The Surprising Friendship between C.S. Lewis and Arthur Greeves (Wipf and Stock, 2022.)