Back to series

Jefferson and Wilberforce:

Jefferson and Wilberforce:

Leaders Who Shaped Their Times

(This is a three-part series on Jefferson and Wilberforce:

Leaders Who Shaped Their Times Part 1, Part 2, Part 3)

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

In contemporary leadership and organizational research, Dr. Peter Senge stands among the most respected scholars in the field seeking to understand why people behave the way they do in large organizations. In a somewhat unique finding, he has framed what he calls the ladder of inference as a way of understanding how people both convey and understand meaning and how they act upon it. Central to his findings is that at the core, an individual’s beliefs lie behind the real meaning in all they say or do.1

His meaning of belief in this context is defined as what people think is true about how the world works, what their understanding is of why people behave the way that they do, and what their own sense is of what is central to their purposeful actions in all of life. Others might use the term worldview to describe this perspective.

Lurking behind all of what we have been seeing so far in the comparison of what shaped the lives of Wilberforce and Jefferson is the notion of contending worldviews. We have examined two factors that played key roles in both men sustaining the commitments they made early in political life to abolishing slavery. Where we have seen this distinction most clearly is not in what they said or wrote publicly, but in the choices they made to act or not to act. In examining so far two sustaining influences—their early mentors and their choice of colleagues and supporters—we have also seen an emerging and a differing worldview that guided each of these men. We now turn to look more closely at the third sustaining factor in more detail—their two worldviews—and how they were lived out in their two visions for abolishing slavery.2

Lurking behind all of what we have been seeing so far in the comparison of what shaped the lives of Wilberforce and Jefferson is the notion of contending worldviews. We have examined two factors that played key roles in both men sustaining the commitments they made early in political life to abolishing slavery. Where we have seen this distinction most clearly is not in what they said or wrote publicly, but in the choices they made to act or not to act. In examining so far two sustaining influences—their early mentors and their choice of colleagues and supporters—we have also seen an emerging and a differing worldview that guided each of these men. We now turn to look more closely at the third sustaining factor in more detail—their two worldviews—and how they were lived out in their two visions for abolishing slavery.2

We will then be in a better position through a summary comparison to understand how and why they chose the course that they did that began to vary so widely. We might also understand how each man shaped the times they lived in long after they were dead. These then are the tasks for this concluding essay.

Saint vs. Hypocrite?

In the starkest of terms, many would conclude that simply by limiting the inquiry to their actions alone, it would seem that Wilberforce set an unswerving course to abolish slavery to his very deathbed because of his beliefs in the equality of all men and that Jefferson, in contrast, abandoned the field because his beliefs radically changed over time. In short, Jefferson was a hypocrite of the first order.

While a tempting conclusion, this is far too simplistic an answer and masks how a leader’s (and politician’s) worldview can help us to understand the distinction between verbal affirmations and consequent actions. More than anything, it was the divergence in their worldviews, their beliefs of how history worked, that most deeply divided the two men and determined the course of action each would follow throughout their mature lives regarding how to engage the fractious political and human issue of slavery.

The Optimist

As we have seen, William Smalls, Jefferson’s first and likely most important mentor, helped to expose Jefferson to the exciting ideas of the Enlightenment that were emerging on the global scene. Space does not allow for a thorough discussion of the new thinking that was being introduced, but for our purposes there are three key beliefs that Jefferson held that illustrate the impact it had on him.

First, he believed the progress of history should be viewed with optimism owing to the power of man’s reason which could only lead to inexorable progress not only materially, but far more so morally. Progress toward equality depended upon the subsequent generations’ further development of the requisite knowledge and moral insight to complete the task of ending slavery.

First, he believed the progress of history should be viewed with optimism owing to the power of man’s reason which could only lead to inexorable progress not only materially, but far more so morally. Progress toward equality depended upon the subsequent generations’ further development of the requisite knowledge and moral insight to complete the task of ending slavery.

Second, the equality of which he spoke was more of a metaphysical equality based upon the notion of individual rights and not revealed moral truths of what it means to be human. He expressed skepticism in his Notes on Virginia that black slaves possessed the requisite mental and moral raw material to ever rise to the level of most white Americans.

And, third, the Enlightenment view was that the tyranny most to be feared was not tyranny of one man over another, but rather that of the King, Executive, or the Federal Government over the rights of individual states. Thus, he would argue later in life that slaves were not men but property because that is what was decreed by many of the state laws of the south and that the Federal government could only override the states in regard to the rights of individuals, not the rights of property. Certain rights trumped others in his mind.

This sense of priority can readily be seen in the remarkable correspondence that was carried between Jefferson and John Adams for the last 14 years of their lives. As these two old revolutionary thinkers and leaders looked back on where they had come as a nation, they attempted to explain what each had done and why, and they shared their hopes for the future.

What interests us is that in all the years of their exchange of letters (they never saw each other after 1800) the subject of slavery was raised only one time. In 1821, Jefferson spoke to the Missouri question as an abridgement of the rights of states to declare slaves free, and tantamount to giving the slaves both freedom and the dagger whereby they might kill their masters. Adams voices his own misgivings, not just about the Missouri issue, but about the “black cloud” of slavery that hung over America for over 50 years. Like Jefferson, he replies, he can only leave it to posterity, but unlike Jefferson, he leaves it to God as well.

The Realist

There is perhaps no better place to contrast the worldview of Wilberforce with that of Jefferson than to return to Wilberforce’s great vision and how he understood his “two great objects:” abolishing slavery and the reformation of manners.

As we have noted, by “manners” he means nothing less than the moral climate of England—the culture embedded in and shaped by the leaders and members of British society at all levels. This is a breathtaking vision that could only be the product of a completely youthful idealist or of someone who actually believed that God, Himself, had cast the vision and would shape the outcome.

Jefferson would most likely have been appalled that an educated political leader, particularly, would make such a proclamation. Jefferson would have viewed such sweeping goals of a political leader as tantamount to a declaration of tyranny of the worst sort—seeking to invoke personal religious beliefs on an entire society and he would have categorically opposed any thought that there even was such a thing as the supernatural direction of God for a human life or a government.

Nevertheless, these two God-inspired goals would be what would animate the rest of Wilberforce’s life and sustain his commitments in the face of the most furious opposition, repeated failure, public derision and even the opposition of the crown. What sustained these goals was that Wilberforce held a particular Christian worldview that contrasted sharply even with the prevailing religious beliefs and resulting practices of his day. For an understanding of this perspective he held and which sustained him and his colleagues, the best source is written in his own hand.

He believed that slavery would not be abolished without a transformation of the prevailing views of society that went well beyond a single issue. Thus, he viewed the “second great object” as critical to the accomplishment of the first. In that task, his strategy was to begin with the head, the leaders of society in persuading them of the need for a radical change of character. Among many other strategies, he took what we might view as an odd turn: he wrote a best selling book. But not just any book, his was a book of practical theology, improbably (to our ears) called A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Higher and Middle Classes in this Country.

His central thesis was that God’s redemptive work in each person’s life was not to be that of the nominal faith so widely practiced in England and among his political colleagues, but a real belief in the historic faith. That faith was revealed best in scripture and was evidenced in daily action and humble service. His own diagnosis of “the grand malady” was not that of the threat of the tyranny of the state, as Jefferson held, but nothing less than selfishness—the tyranny of self gratification above all. In an age where faith was kept on a leash and separate from the crucible of power and choices in life, his was a voice that was unique. And it had an immediate impact becoming a widely read best seller in both England and later in America. Lincoln was said to have been strongly influenced as a boy by Wilberforce’s life story and later by his writing.

In the end, Wilberforce was to be the champion of over 70 bills that became law leading to vast changes in child labor, the exploitation of women and the poor, and even the first effort to prevent cruelty to animals. The end result was, as one commentator observed, “he made it fashionable to do good.”

Stemming from his Christian worldview was an understanding of what it means to be human that marked another contrast with Jefferson. As we have seen, Jefferson’s view of slaves included that they were to be considered property and that their capacities were limited in potential for absorption into the culture. Once slavery ended in the far off future, Jefferson saw slaves as being returned to Africa. In contrast, Wilberforce’s views of the slaves as persons can perhaps best be described in the strategy discussed in the previous essay which he developed with fellow Christian Josiah Wedgwood, the famous designer and manufacturer of prestigious lines of fine China.

The conversation “starter” of a China charger plate with a kneeling black man, in chains, his hands uplifted in prayer was more than an intriguing gambit. The words on the plate, “Am I not a man and a brother?” were an expression of a central belief that animated Wilberforce and, in that day, were also a distinctively evangelical Christian worldview. It is interesting to speculate what Jefferson’s reaction would have been had he been a guest at Wilberforce’s table.

A Comparative Summary

Our task has been to try to gain an understanding of what it was that might have shaped the commitments of Thomas Jefferson and William Wilberforce as their lives sailed further away from their commitments as young, rising politicians. Many possible explanations have presented themselves along the way under the rubrics of their mentors, their colleagues and supporters, and their worldviews. We can at this point summarize them comparatively as a way to fill out the entire picture. In the end, there is one last explanation for their divergence that we have yet to touch upon.

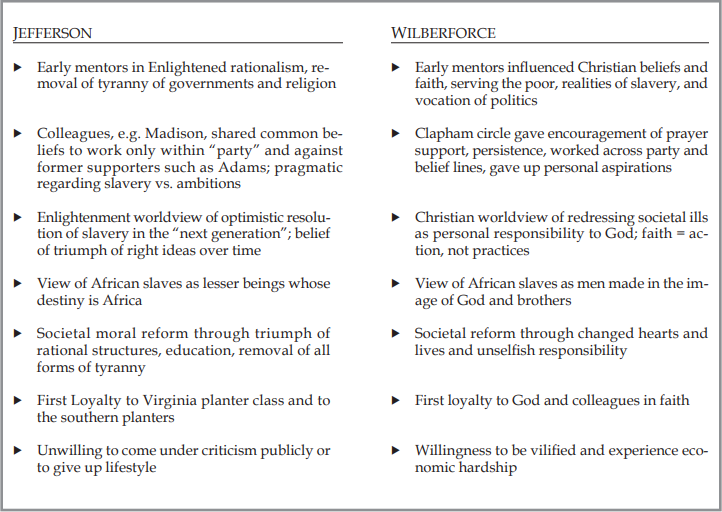

[Refer to the chart for a comparative summary.]

Two Legacies

The notion of a person’s legacy in life has taken on much interest in recent decades. It is perhaps most prominently and publicly discussed when the term of a President is nearing its end and many of the penultimate acts are interpreted by journalists as enhancing the leader’s legacy. But what of the legacies of Jefferson and Wilberforce: what did they leave behind for the next generations, and what were their own views of their legacy?

Planned Yet Unanticipated

Interestingly, Jefferson was very fastidious about how he wanted history to remember him, even designing the obelisk he wanted to mark his grave and its inscription:

Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, of the Statute of Virginia

for religious freedom and Father of the University of Virginia.

He then added, “because of these as testimonials that I have lived, I wish most to be remembered.”

It might also be added—with the benefit of our view from history—that he, himself, was mentor to two future leaders and Presidents, both fellow Virginians and neighbors, Madison and Monroe. Both would perpetuate Jefferson’s avoidance of the slavery issue as a matter to be resolved politically, despite the growing seriousness of its divisiveness in America north, south, and west. But yet on a personal level, both men would, unlike their patron, free their slaves upon their deaths.

Despite his unarguably superior accomplishments and visionary leadership, it may be seen that Jefferson’s legacy lies as well in what was not done with the opportunities he had and the consequences of a failure to act in accord with belief. His optimism that history and the intellectual and moral progress of man would resolve the black cloud that hung over them proved wrong. Never would he have foreseen that the lives of over six hundred thousand Americans would be given to keep intact the union his generation had forged and finally resolve the question on which they stood silent for so many years.

Humbly Transforming a Culture

Wilberforce, much like Jefferson, had leaders coming behind him whom he had influenced and who would carry on his work. By 1823, he was obviously becoming more frail and subject to attacks of inflamed lungs (pneumonia?) which laid him low for weeks or months at a time. Yet his two great objectives still animated his life. While the abolition of slavery was gaining momentum, it was by no means complete. He was reluctant to step down feeling he had not done enough!

Nevertheless, he prepared to pass the mantle on to Thomas Buxton, a Quaker M.P. who shared Wilberforce’s views on abolition and had been a leader in prison reform. Wilberforce saw Buxton almost as much as a son as a colleague in the fight. In a letter, he warns Buxton of the difficult road ahead and then shares his own hard earned lessons of leadership:

Nevertheless, he prepared to pass the mantle on to Thomas Buxton, a Quaker M.P. who shared Wilberforce’s views on abolition and had been a leader in prison reform. Wilberforce saw Buxton almost as much as a son as a colleague in the fight. In a letter, he warns Buxton of the difficult road ahead and then shares his own hard earned lessons of leadership:

If it be His will, may he render you an instrument of extensive influence . . . [But] above all, may He

give the disposition to say at all times “Lord, what wouldest thou have me to do or suffer?” looking to

Him, through Christ, for wisdom and strength.

Buxton would go on to introduce the bill, and with Wilberforce supporting and advising him, the last race began that would end literally on Wilberforce’s deathbed when the bill finally passed in 1833.

His own view of his legacy was far different than Jefferson’s. Despite over 50 years of laboring for the abolition of slavery and championing dozens of worthy causes for oppressed people, all he could say of himself was “God be merciful to me, a sinner.”

A Final Note

There is one final explanation for the divergent outcomes and legacies of the lives of the two men who made early commitments to abolish slavery that may be more telling than any historian has noted to date: the sovereignty of God.

When Wilberforce was first taking up his task, the aged John Wesley wrote to encourage him and to warn him. “Unless God has raised you up for this very thing, you will be worn out by the opposition of men and devils; but if God be for you who can be against you?”3 Why God raised up a Wilberforce in England, brought him together with a Newton, and surrounded him with the Clapham circle during his life, we will never know. We do know it was a sovereign act of grace.

For Jefferson, the belief in sovereignty ran equally strong: the sovereignty of man. It was the central core belief of the Enlightenment that man would ultimately triumph and secure moral progress through ideas and through education freed from religious cant. And many in America felt that way in his time. Why God did not raise up a Wilberforce in America and why so many died to end slavery and leave a legacy that haunts the United States even today is also something we will never know. We do know that the great leaders of the North and the South, Grant and Lee, acknowledged the providence of God in the outcome and it humbled both men. This, too, we know as a sovereign act of God’s grace. Not why, but Who.

Even as we have examined these two lives and sought to understand them, we remain awed by what Wilberforce and his friends were able to accomplish and the legacy they left. Perhaps John Newton draws the conclusion best in a letter he wrote to a young Wilberforce in 1796 urging him to remain in the political vocation and not withdraw from public life. He counseled that God’s grace would be sufficient and that “Happy the man who has a deep impression of the Lord’s words, ‘Without me you can do nothing.’”4 For the next 37 years Wilberforce took that scriptural wisdom to heart. To God be the glory.

Notes

1. Peter Senge, The Fifth Discipline,

2. The three-part framework for the discussion in the three papers is drawn from Dr. Steven Garber as set forth in his marvelous book, The Fabric of Faithfulness.

3. Wesley as cited in Kevin Belmonte, A Hero for Humanity, p. 138

4. Newton as cited in Kevin Belmonte, Ibid.

Ray Blunt

ProfessorRay Blunt, Professor, teaches philosophy and worldview at Ad Fontes Academy high school and is a Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation, and Culture. He was previously an Adjunct Professor for Leadership and Business Ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. A 1964 graduate of the U.S. Air Force Academy, he holds a master’s degree in economics and political science as well as master’s in theological studies. He is the author of numerous articles on leadership, character, vocation, and change management and two books: Crossed Lives, Crossed Purposes: Why Thomas Jefferson Failed and William Wilberforce Persisted to Lead an End to Slavery, Wipf and Stock, 2012, and “Leaders Growing Leaders” in The Jossey-Bass Reader on Nonprofit and Public Leadership, 2011.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Philosophy and Influence

by David George Moore on July 26, 2024Ralph Waldo Emerson was a gifted nineteenth century...Read More

-

The Side B Stories – Nate Sala’s Story

by Jana Harmon, Nate Sala on July 19, 2024

-

Terrorism Through the Eyes of Faith

by Dennis Hollinger on July 12, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Hasn’t Science Proven That Belief in God Is an Outdated Superstition?

by Sharon Dirckx on July 1, 2024Many assume that scientific practice and belief in...Read More

-

Has the Bible Been Corrupted as Some Muslims Claim?

by Andy Bannister on June 1, 2024

-

Seeing Jesus Through the Eyes of Women

by Rebecca McLaughlin on May 15, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

22194

C.S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man Live Online Small Group 8:00 PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=c-s-lewiss-the-abolition-of-man-study-course&event_date=2024-10-02®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-10-02

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

C.S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man Live Online Small Group 8:00 PM ET

On October 2, 2024 at 8:00 pmSpeakers

Ray Blunt

Professor

Team Members

Ray Blunt

ProfessorRay Blunt, Professor, teaches philosophy and worldview at Ad Fontes Academy high school and is a Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation, and Culture. He was previously an Adjunct Professor for Leadership and Business Ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. A 1964 graduate of the U.S. Air Force Academy, he holds a master’s degree in economics and political science as well as master’s in theological studies. He is the author of numerous articles on leadership, character, vocation, and change management and two books: Crossed Lives, Crossed Purposes: Why Thomas Jefferson Failed and William Wilberforce Persisted to Lead an End to Slavery, Wipf and Stock, 2012, and “Leaders Growing Leaders” in The Jossey-Bass Reader on Nonprofit and Public Leadership, 2011.