Back to series

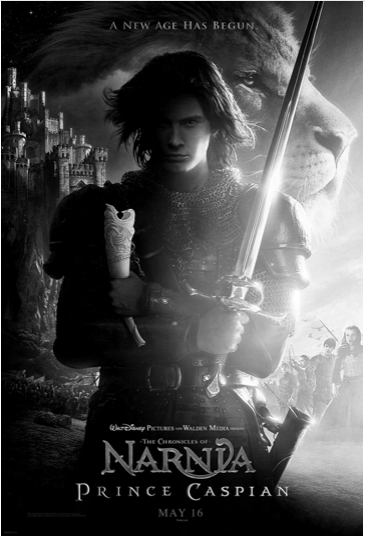

Coming to a Screen Near You: Prince Caspian

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

The film version of C.S. Lewis’s Prince Caspian, the next in the Narnia series, is due to be released in May. It remains to be seen if the sequel will do better than the original film, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (now listed as the 26th all-time best-grossing film). If the pattern for the Narnia films is similar to that of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, it will do better. The Fellowship of the Ring (first in the Lord of the Rings series) is number 14 of all time, The Two Towers (second in the series) is number 7, and The Return of the King (third in the series) is now number 2.

Though Prince Caspian may do better at the box office, its message may not be as readily understood as that of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. In the latter, we have Narnia rescued from the grip of the White Witch, who makes it “always winter, never Christmas.” In Prince Caspian, it is summer but without a Fourth of July. Narnia has been taken over by an evil King Miraz. The talking animals are in hiding, and the trees are silenced. The King (knowing better) says that there was never an Aslan, no talking animals, no High Kings and Queens such as Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy. Everything has deteriorated and is in desperate need of restoration.

Even though only about a year has passed since Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy have entered Narnia, their return (from the platform of a train station) puts them back into Narnia many years later. Time is different in Narnia than in our world. This return, we find out, is in response to the blowing of a horn given to Susan in the first book, only to be used in extreme situations. This return is the subtitle of the book, The Return to Narnia, and a key theme. Douglas Gresham (C.S. Lewis’s stepson) says:

A theme of return became a key part of the story. Jack didn’t look at return in the obvious physical sense, but went deeper to consider a restoration, a restoration of those things that are true—true life, true leadership, and mostly, true faith. Prince Caspian tackles that idea, and broader themes of the battle between good and evil, spiritual obedience and discernment, and ultimately joy – a festive joy when what was wrong has been put right again.

C.S. Lewis makes the point in one of his letters that Prince Caspian is about “the restoration of the true religion after corruption.” Although the victory was won in Book One, a spiritual entropy went into effect, leading to a decline and loss of faith. In fact, one central theme of the novel is the importance of faith (trust) and the consequences of unbelief. King Miraz is the ultimate example of willful spiritual blindness. He knows that Aslan exists, that the talking animals are real, and that there were High Kings and Queens —Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy—yet he tells everyone, including Prince Caspian, that such beliefs are “fairy tales.”

C.S. Lewis makes the point in one of his letters that Prince Caspian is about “the restoration of the true religion after corruption.” Although the victory was won in Book One, a spiritual entropy went into effect, leading to a decline and loss of faith. In fact, one central theme of the novel is the importance of faith (trust) and the consequences of unbelief. King Miraz is the ultimate example of willful spiritual blindness. He knows that Aslan exists, that the talking animals are real, and that there were High Kings and Queens —Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy—yet he tells everyone, including Prince Caspian, that such beliefs are “fairy tales.”

Miraz has not only killed Prince Caspian’s father, but is willing to kill the Prince (when the Queen has a child). He denies what he knows is true and wants everyone else to believe the lies. Other prime examples of unbelief are Nikabrik (the Dwarf) and leaders in Miraz’s army, Lord Glozell and Lord Sopespian. Nikabrik is willing to use a witch to call up from the dead the White Witch (who made it always winter) in order to beat King Miraz. When asked whether this might make things worse, he replied that she always treated the Dwarfs well, and that’s all he was concerned for—his own people. He also didn’t believe in Aslan, or the stories of High Kings or Queens. Glozell and Sopespian believe only when they see Edmund and Peter, and conspire to kill King Miraz—stabbing him in the back.

Lucy is the prime example of belief and trust. She alone sees Aslan, who indicates which direction they are to go. When she tells the others, they don’t believe her and vote to go the opposite direction. Rather than go by herself in the direction Aslan wants, Lucy follows the rest. They have all kinds of problems and come to a dead end. In the end, they have to go back the way Aslan (and Lucy) wanted. As they sleep that night, Lucy wakes up and walks into the wood. She sees Aslan again, and he directs her to wake the others and tell them to follow her as she follows Aslan. Again they are reluctant to believe her (just like with the wardrobe) but eventually follow. One by one they see Aslan and believe Lucy. The last to see him is the doubter Trumpkin.

Trumpkin is a dwarf who was sent to find help, but he has been reluctant to believe in Aslan. He is like doubting Thomas. Finally, when Trumpkin meets the lion, Aslan says, “Son of Earth, shall we be friends?” Trumpkin replies with the only word he says to Aslan in the whole book, “Yes.”

Another theme in Prince Caspian is obedience. One example is what Aslan teaches Lucy. When she wakes the others, she is to tell them to follow this time, and Aslan says, “If they will not, then you at least must follow me alone.” They do follow her reluctantly. Later, when Peter meets Aslan, he says, “I’m so sorry. I’ve been leading them wrong ever since we started and especially yesterday morning.” Aslan’s response is, “My dear son.” Thus, it is through obediently following that it is possible for the victory to be won.

Another important theme is community. Particular emphasis could be placed on the importance of diverse races working together: humans, dwarfs, centaurs, giants, badgers, and even the trees. It is through their cooperation that they are able to overcome Miraz’s forces. Cornelius, Caspian’s tutor, is looked down on by Nikabrik because he is a half and halfer—half dwarf and half human. It is clear that this kind of racism is wrong.

Yet another theme is the importance of celebration. When the five (Peter, Susan, Edmund, Lucy, and Trumpkin) meet Aslan, there is a scene where Aslan roars. Beings from everywhere are awakened to celebrate and worship Aslan: nymphs, the river god, rabbits, birds, owls, dogs, hedgehogs, and trees. The crowd dances around Aslan. One young man was dressed in fawn skin and had vine leaves wreathed in his hair. Edmund said about him, “There’s a chap who might do anything.” There were lots of girls with him as wild as he was. They all romped and played games. We find out that the young chap’s name is Bacchus (the Greek god). Susan says about him, “I wouldn’t have felt safe with Bacchus and all his wild girls if we’d met them without Aslan!” “I should think not,” said Lucy.

In another scene, early on the morning before the battle, Aslan says to the girls, “We will make a holiday.” The story has Aslan leading the animals, Bacchus and his Maenads leaping, rushing, and turning somersaults. Note that it says, “Aslan leading,” they proceed to bring freedom to Narnia from those things that have diminished life. Lewis says in The Problem of Pain:

The settled happiness and security which we all desire, God withholds from us by the very nature of the world: but joy, pleasure and merriment He has scattered broadcast. We are never safe, but we have plenty of fun, and some ecstasy.

Celebration is something regularly found in the Old Testament feasts. In Deuteronomy 14:24-27 it even says that at times it is appropriate to use a tithe (a tenth of our income) to throw a feast with everything we desire. It does point out that when we do so everyone is to be included: servants, aliens, widows, and orphans. Jesus was no stranger to feasts—sometimes accused of being with those who ate and drank too much. There certainly are times to save and exercise caution, but there are also times to dance and feast.

Consistent with Lewis’s emphasis on Jesus being “the myth become fact,” it is not surprising to see mythical gods being referenced. Lewis defined myth as “a real though unfocused gleam of divine truth falling on human imagination.” He saw mythical stories and characters as cosmic pointers to Christ. Jesus catches up in himself all the best of the myths and mythical characters. Note that throughout Prince Caspian the mythical gods such as Bacchus and Silenus follow Aslan’s lead and are under his authority. The dancing and the feasting after the victory is described in detail (particularly the foods).

Devin Brown, in his book, Inside Prince Caspian, notes a couple of other themes. First, evil appears rarely as evil but in some other form. Second, help often comes in an unanticipated form and in a strange manner, perhaps only recognized as help when looking back. They all expect Aslan to appear as he did before in the first book and, with a roar, defeat the enemy. Aslan says: “But things never happen the same way twice.”

Other interesting insights:

- Although all the others get gifts, Edmund goes through Prince Caspian without a gift. He wasn’t there when Father Christmas gave them gifts in the first book.

- The kids have skills, e.g., sword fighting and archery, from their time as Kings and Queens. The gifts gradually return.

- Trumpkin’s expletives always start with the same sound: “whistles and whirligigs,” “thimbles and thunderstorms,” “tulips and tortoiseshells,” etc.

- Often in Lewis’s stories the heroes or heroines are either without a parent (or both parents) as Lewis was when he was young, or they are in the background, rarely mentioned.

- Queen Prunaprismia’s name likely comes from a well-known passage from Charles Dickens’ book, Little Dorrit, where prunes and prisms are mentioned numerous times. Lewis hated prunes.

- When Lewis was young, he had a beloved nurse.

- Prince Caspian’s nurse is cruelly removed from his life by King Miraz for telling him some of the old stories. The nurse and Prince Caspian are reunited towards the end of the book.

- When Cornelius and Caspian are up on the tower roof, they hear the waterfall at Beaversdam, perhaps alluding to the gift of an improved dam to Mr. Beaver by Father Christmas (in the first book).

- The evil Telmarines cut down the trees, similar to the forces of Sauron in Lord of the Rings. The trees get their revenge in a similar fashion.

- Susan the Gentle turns into Susan the Grouch.

- Aslan does not condemn doubt. When Aslan meets Trumpkin, he says, “Where is this little Dwarf…who doesn’t believe in lions?” Later it says that Aslan “liked the Dwarf very much.”

- Lewis liked nicknames. In Prince Caspian, Trumpkin is called DLF (Dear Little Friend), a kind of inside joke. In Lewis’s life Tolkien was called Tollers, the pub Eagle and the Child was called the Bird and the Baby, Dr. Havard was called UQ or “Useless Quack,” and his work on 16th century English literature called OHEL.

While I write all this analysis of themes, I am aware of what Lewis might say to me. “Let the pictures teach the morals.” Perhaps you can teach by not trying to teach. Analysis should only come after enjoyment. Enjoy the movie and enjoy the book. Then you will be in the position to talk about it. We will be in the position again of being able to use C.S. Lewis’s popularity to open doors of discussion about eternal things.

Arthur W. Lindsley

Senior Fellow for Apologetics, CSLI Arthur W. Lindsley is the Vice President of Theological Initiatives at the Institute for Faith, Works, & Economics. He has served at the C.S. Lewis Institute since 1987 both as President until 1998 and currently as Senior Fellows for Apologetics. Formerly, he was director of Educational Ministries at the Ligonier Valley Study Center, and Staff Specialist with the Coalition for Christian Outreach. He is the author of C.S. Lewis's Case for Christ, True Truth, Love: The Ultimate Apologetic, and co-author with R.C. Sproul and John Gerstner of Classical Apologetics, and has written numerous articles on theology, apologetics, C.S. Lewis, and the lives and works of many other authors and teachers. Art earned his M.Div. from Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and a Ph.D. in Religious Studies from the University of Pittsburgh. COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

A Welcome Change in Apologetics

by Randy Newman, Aimee Riegert on April 19, 2024We’re burdened for our friends who don’t know...Read More

-

Questions That Matter Podcast – Samuel James and Digital Liturgies

by Samuel James, Randy Newman on April 19, 2024

-

The Side B Stories – Dr. James Tour’s story

by Jana Harmon, James Tour on April 12, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Isn’t Morality Relative?

by Christopher L. Reese on April 1, 2024It is widely accepted in the Western world...Read More

-

Do Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God?

by Andy Bannister on March 1, 2024

-

Artificial Intelligence and Its Impacts on Humanity

by John Lennox on February 13, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

22140

GLOBAL EVENT: Keeping the Faith From One Generation To Another with Stuart McAllister and Cameron McAllister, 8:00PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=global-event-keeping-the-faith-from-one-generation-to-another-with-stuart-mcallister-and-cameron-mcallister-800pm-et&event_date=2024-05-17®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-05-17

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

GLOBAL EVENT: Keeping the Faith From One Generation To Another with Stuart McAllister and Cameron McAllister, 8:00PM ET

On May 17, 2024 at 8:00 pmSpeakers

Arthur W. Lindsley

Senior Fellow for Apologetics, CSLI

Team Members