Back to series

Profile in Faith

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

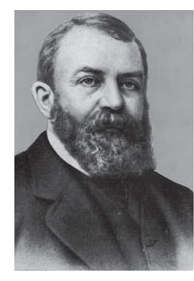

The reputation of Dwight L. Moody had been well established prior to his death in 1899. Although the famous evangelist was only sixty-two years old when he died, he had already preached the gospel to more than 100 million people. This energetic and widely admired preacher with seemingly unbounded passion to see souls come to faith held the distinction of having preached to more people than anyone in history.

Nothing in Dwight Moody’s early life suggested he would become internationally famous. On the contrary, this remarkable man, born into abject poverty in 1837 in rural Massachusetts, never secured more than four years of formal schooling. Forced to leave home at age ten and find work as a farm hand and living without benefit of a strong Christian upbringing, Moody became an anointed preacher whose name was known in most American households and in Great Britain. What few people know—even folk well informed about the history of Christianity in the English-speaking world—is that Dwight Moody was much more than an evangelist whose preaching led innumerable souls to Christ. Mr. Moody became one of the most effective disciple makers of church history.

Throughout his adult life, Moody emphasized “This one thing I do,” referring to God’s call on his life to work with souls.

Throughout his adult life, Moody emphasized “This one thing I do,” referring to God’s call on his life to work with souls.

From his devotion to full-time ministry that began soon after his conversion at age nineteen, it is apparent that he was referring to a call that encompassed the healing and nurture of souls as well as evangelism.

Moody always took the biblical view that the Great Commission calls us to make disciples not mere converts.

Consequently he labored tirelessly to help people grow into strong, reproductive disciples, and he also labored to equip other men and women to become full-time workers in this broader disciple-making ministry.

Moody absolutely delighted in “the work,” as he dubbed his ministry. In one of his last letters, he referred to both the formal and nonformal educational programs he founded, which he believed were his most significant enterprises: “The work is sweeter now than ever, and I think I have some streams started that will flow on forever. What a joy to be in the harvest field and have a hand in God’s work.” Just a few months before his death, Moody told his oldest son that his efforts to train the upcoming generation of young people “are the best pieces of work I have ever done.”

Conversion

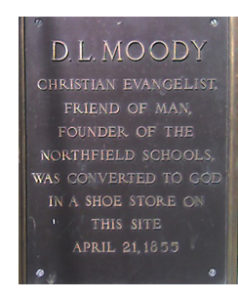

Dwight Moody’s life in Christ began when he left the hardscrabble soil of northwestern Massachusetts. Leaving behind his grinding labor as a farm hand, the restless teen moved to Boston, where he found employment in an uncle’s shoe store. Moody’s godly relative provided room, board, and a day job to his seventeen-year-old nephew with one condition: he must faithfully promise to attend Sunday school and church every week.

Young Moody kept his promise, and Uncle Lemuel Holton witnessed the answer to his prayers. Dwight heard the gospel story from his Sunday school teacher, Edward Kimball, who one Saturday stopped by Holton’s shoe store where he found Dwight alone. Moody never forgot the day Kimball came behind the counter “and put his hand upon my shoulder, and talked to me about Christ and my soul. I had not felt I had a soul till then.”

Young Moody kept his promise, and Uncle Lemuel Holton witnessed the answer to his prayers. Dwight heard the gospel story from his Sunday school teacher, Edward Kimball, who one Saturday stopped by Holton’s shoe store where he found Dwight alone. Moody never forgot the day Kimball came behind the counter “and put his hand upon my shoulder, and talked to me about Christ and my soul. I had not felt I had a soul till then.”

Moody stood astounded by the presence of this man who had known him only a few weeks yet wept over his sins. Years later Moody said, “I don’t remember what he said, but I can feel the power of that man’s hand on my shoulder tonight.” Within a few months, the young shoe store clerk surrendered his life to Christ and expressed a willingness to repent and be mentored in the faith by Edward Kimball and a few other men in Boston’s Mount Vernon Congregational Church. The young convert admitted that he soon found himself in “a conflict with my will. I had a terrible battle to surrender my will, and to take God’s will.”

An Impetuous Move

Late in life D. L. Moody told his oldest son, William, that he had “always been a man of impulse. Almost everything I ever did in my life that was a success was done on impulse.” Leaving the family and moving to Boston in 1854 was impulsive. And so was the decision in autumn 1856 to leave Boston and travel a thousand miles west to Chicago—a fast-growing little city on Lake Michigan. The Windy City did not exist until 1830, but by the time of Moody’s arrival the population had reached 84,000. Four years later the rapidly growing gateway city to the West had burgeoned to 112,000.

Moody moved to the booming Midwestern metropolis on impulse but God had clearly gone before him to open the way. The impetuous New Englander expressed an ambition to acquire assets of $100,000—a fortune by any standard in an era when most working men earned no more than a dollar a day. Soon after his arrival, the determined New Englander began to prosper by selling boots and shoes and investing his profits in Chicago’s lucrative real estate market. Before Illinois’ favorite son Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860, Moody boasted he was debt free, had saved more than $12,000, and continued to watch his income grow higher with every passing month.

Despite his ambition to earn money, Moody purposively pursued his walk with the Lord. Soon after his arrival in Chicago, he began rooming and taking meals in the house of “Mother” H. Phillips. Mrs. Phillips not only housed and fed Moody, she held him accountable to pray and read his Bible daily and attend services at First Baptist, her home church. But Mother Phillips did more than mentor Moody; she encouraged him to assist her in city mission work. Thanks to the witness of this godly woman, Moody began an outreach to a growing throng of street children—thousands of impoverished boys and girls who roamed the streets and alleys of the neighborhoods where the lowest social and economic classes lived.

Foundational Experiences

If Dwight L. Moody began to realize his ambition to make money, he did not forget his own childhood of poverty and the needs of his mother and siblings. Indeed, he regularly sent money to his mother, enabling her to own and maintain the family house in Northfield and provide for her needs and those of his younger siblings.

In late 1856 and well into 1857, a religious revival broke out in Chicago. Moody and many other business men found themselves going to prayer meetings at lunchtime and worship services most evenings. As a result of seeking a closer walk with the Lord, the twenty-two-year-old lad from Massachusetts grew increasingly restless. While continuing to buy and sell city lots on speculation, as well as marketing boots and shoes, Moody discovered more fulfillment in child evangelism and late-night witnessing to sailors and laboring men who lived, worked, and drank to excess along the docks of Lake Michigan.

During his open-air evangelistic outreaches along the lakefront, Moody met J. B. Stillson, a man at least twice his age who served as a spiritual father. He taught his young disciple how to study the Bible.

During his open-air evangelistic outreaches along the lakefront, Moody met J. B. Stillson, a man at least twice his age who served as a spiritual father. He taught his young disciple how to study the Bible.

He also introduced him to study aids such as a concordance and Bible dictionary. Stillson not only taught Moody how to get riches from the Bible in more systematic and contextual ways, he introduced his young protégé to George Müller’s A Life of Trust.

This book, plus the ever-growing nuggets he began to glean from Scripture, helped the spiritually alert young man discern a gift of faith and a growing calling to the rescue and care of souls.

At the onset of the Civil War in April 1861, Moody was increasing his commitment to evangelistic work among Chicago’s poorest street children—herding them into a one-time saloon he turned into a mission school and recruiting volunteers to help tame and teach the destitute children whom no one, not even the committed Christians in the mainline churches, knew how to reach.

It became apparent to everyone who knew Moody that he had been blessed with a sacred anointing. His ability to rescue children, introduce them to Jesus Christ, and help them to form Christ-honoring lives was phenomenal. It likewise grew evident that Moody had a unique ability to find facilities to house a mission school for boys and another for girls. He also did more than find buildings; like a magnet he attracted a following of businessmen who eagerly dug into their pockets for money to purchase property and support “the work.” Additionally, Moody attracted young women and men to help nurture and teach the children. Among them was Emma Revell who would eventually become Dwight’s wife and the love of his life. In brief, Moody became an American George Müller.

As Moody imbibed deep drafts of Scripture and spent increasing time in prayer and ministry, he gradually turned from business to full-time ministry. Worldlings called Moody “crazy,” because he gave up his lucrative real estate and business ventures to “waste time” on dirty and rowdy children. But for Mr. Moody, going into full-time Christian service was neither insane nor impulsive. On the contrary, he gradually and prayerfully followed the Lord’s guidance one step at a time. When acquaintances chided, “What are you doing now, Moody?” his joyful response remained the same: “I am working for Jesus Christ.”

Wartime Ministries

By the time of his twenty-fourth birthday in 1861, Moody was listed in the Chicago city directory as “city missionary.” This generic label was quite appropriate. Moody worked without pay as an evangelist for Chicago’s Young Men’s Christian Association. To conserve money for ministry, he lived in the modest YMCA building, sleeping on a line of chairs that he covered with old newspapers for a mattress. Eventually a group of devout Christian businessmen, among them John V. Farwell, a dry-goods merchant who became one of the wealthiest men in the booming Illinois metropolis, discovered Moody’s living arrangements. They immediately agreed to provide monthly stipends to Moody so he at least would have a comfortable place to live and a diet of more than cheese and crackers.

A watershed in Moody’s life and ministry occurred in 1862. He and Emma Revell married and began a beautiful marriage that produced three children. That same year Moody, under the covering of the YMCA and the Illinois Christian Commission, became a chaplain to General U. S. Grant’s soldiers.

While four years of fratricide raged, Moody ministered to Union soldiers in Grant’s army. In the winter months, during lulls in fighting, he conducted evangelistic services and Bible classes for large gatherings of soldiers. He also visited Confederate troops in prison camps—happily sharing the good news and food from the Bible to the soldiers in gray. At times of heavy combat, Chaplain Moody was usually found in field hospitals, where he would engage in one-on-one personal work.

While four years of fratricide raged, Moody ministered to Union soldiers in Grant’s army. In the winter months, during lulls in fighting, he conducted evangelistic services and Bible classes for large gatherings of soldiers. He also visited Confederate troops in prison camps—happily sharing the good news and food from the Bible to the soldiers in gray. At times of heavy combat, Chaplain Moody was usually found in field hospitals, where he would engage in one-on-one personal work.

In these tents and make-shift field hospital buildings, Moody would go from man to man, listening to their confessions, praying for them, and helping them send letters to loved ones—regardless of the color of their uniform.

Postwar Work

The personal work became a school of practical ministry for the poorly educated evangelist. There he learned to listen to God as he listened to broken men. While he never ceased to believe in the importance of preaching to large crowds, Moody came to understand the supreme importance of personal ministry. In the same way that Edward Kimball had laid his hand on young Moody’s shoulder and then prayed for the healing and salvation of his soul—so Dwight Moody discovered the power of placing his hand on the forehead, arm, or hand of wounded and dying men as he prayed for their peace, comfort, and salvation.

By the war’s end in 1865, Moody knew that preaching, teaching, and personal ministry comprised his life’s work. He also met and began to mentor men who knew even less about ministry than did he. During those tumultuous years, Moody trained men and women to evangelize and disciple children in the poorest sections of Chicago. And he helped equip men and women to join him in doing evangelistic and disciple-making work among adults.

Prior to the middle of the twentieth century, the YMCA maintained a decidedly evangelistic focus. The association’s workers were called to evangelize the unsaved and make disciples who could reproduce their kind among the converts. Moody took a lead in preaching, teaching, and fundraising under the auspices of the YMCA. And he also planted a church in the heart of Chicago, where the poorest of the city’s poor would attend and be comfortable alongside people of more means.

Moody’s ministry grew so rapidly after the Civil War that out of necessity he was led to train people as helpers who were equally committed to Christ and his kingdom. Among those Union combatants he met during the war, Major D. W. Whittle became one of his closest and dearest friends. Moody became an encourager of Whittle soon after the young officer was severely wounded at Vicksburg in 1863. And after the war, when Whittle returned to Chicago and became an executive with the Elgin Watch Company, Moody drafted him to help out with Bible studies for new believers. Moody also encouraged Major Whittle to accept some speaking and preaching engagements. Then in 1873 Whittle learned what his mentor and friend had learned over a decade earlier: if God taps you on the shoulder to enter full-time ministry, you find no peace until you obey.

Soon after D. W. Whittle answered the call to a life of preaching and disciple making, he in turn mentored Paul P. Bliss who taught music in Chicago. Moody had urged Bliss to become a music evangelist, and Whittle walked alongside the able vocalist and song writer. By 1874 Bliss teamed up with Whittle and the twosome of Whittle and Bliss became an anointed and popular evangelistic team in the same vein as D. L. Moody and Ira Sankey, who traveled throughout the United States and Great Britain preaching and singing the gospel.

A Multifaceted Ministry

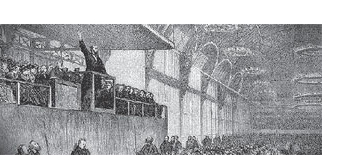

By 1870 Dwight L. Moody and his song leader Ira Sankey spent at least half of their time holding evangelistic crusades. Eventually Moody would preach the gospel and Sankey would sing the Good News to more than 100 million people. There is no way to quantify the effect of this ministry. Sufficient to say, tens of thousands became believers or recommitted their lives to Jesus Christ and found healing and freedom from various bondages.

Because of his experiences with Edward Kimball and his field hospital ministry during the Civil War, Moody knew he must find ways for the crowds who heard him preach to get individual care. Out of the necessity to help the seekers at his meetings in America and abroad, Mr. Moody sought the help of local churches wherever he preached. Before his big preaching crusades that typically lasted from one to six weeks, he sought the assistance of local pastors and lay leaders in identifying people he could train for “inquiry room” consultations. Moody believed that at the end of his sermons people should not be pressured to come forward and “accept Christ.”

Instead, he invited people to visit “inquiry rooms” after the message. There they could ask questions about the message, the Bible, or issues involving their souls. In those unhurried environments, men, women, and children were not only encouraged to ask questions, they were invited to seek prayer for salvation, inner or physical healing, or sundry needs and burdens. And finally, to be sure, folks were encouraged to attend local churches for baptism and membership.

Instead, he invited people to visit “inquiry rooms” after the message. There they could ask questions about the message, the Bible, or issues involving their souls. In those unhurried environments, men, women, and children were not only encouraged to ask questions, they were invited to seek prayer for salvation, inner or physical healing, or sundry needs and burdens. And finally, to be sure, folks were encouraged to attend local churches for baptism and membership.

In the wake of such meetings, thousands not only heard the gospel and made a decision to turn to Christ; a maturation process bolstered by face-to-face counsel, encouragement to read Scripture and pray, as well as invitations to become connected to Bible-teaching, Christ-honoring churches where wholesome fellowship could be found became the order of the day.

Besides these impetuses for converts and new Christians to grow, countless men and women experienced God’s call to Christian service. Indeed, Moody and his fellow workers were frequently asked for advice about entering full-time service, and the requests to be mentored and trained for Christian ministry became so common that Moody knew he could not ignore them.

When those who sought guidance toward ministry were university educated and economically stable—like Henry Drummond and R. A. Torrey—Moody’s task was simple. They were invited to travel with the team and be mentored for ministry along the way. In fact, Moody was able to help both of these men build upon and apply their extensive educations and point them to places where they almost immediately could become useful in “the work.” But many men and women who came to Moody for help came from backgrounds similar to his. They grew up in rural or urban poverty, and they had little or no education beyond the elementary levels of reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Moody’s heart went out to such people and consequently “the work” took on new and formal dimensions. In his home base, Chicago, Mr. Moody managed to recruit a college professor from Illinois State Normal University, Emma Dryer, to oversee a training school for women who felt called to home and foreign mission work. Already by 1879 a local historian called it “Mr. Moody’s Theological Seminary.” Of course it was hardly sophisticated enough for that lofty title, but within a few years the Chicago Bible Training School for women opened its doors to men. Gradually a small work for women became the Chicago Bible Institute that, after Moody’s death, became Moody Bible Institute that remains strong to this day.

The Chicago school proved to be a mere prelude to the planting of other educational institutions. Mr. Moody began to share his ever-widening vision to see men and women, both young and old, be mentored and educated as part of “the work” to spread the gospel all over America and to the ends of the earth. Moody networked with prosperous men in Chicago, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia—among them John Farwell the Chicago dry-goods king; John Wannamaker, a Philadelphia department store magnate; Philip Armour, the meat-packing mogul; Colonel Julius J. Estey, of Estey Organ Company fame; and philanthropists such as Mrs. Cyrus P. (Nettie) McCormick. Moody personally invested in these people—helping them to grow in their faith and unabashedly asking them to help underwrite training for economically deprived young people. In the final analysis, a powerful network of Christian philanthropists, educators, and ministers formed that enabled several of Moody’s visions to become reality.

Besides building a church and school in Chicago, Moody secured property in Northfield, Massachusetts. With the help of his prosperous supporters, the increasingly famous evangelist bought land and erected buildings near his birthplace where Mother Moody lived until her death a few days before her ninety-first birthday in 1896.

Because Dwight and Emma Moody and their three children lived humbly and frugally in Chicago or with Mother Moody in Massachusetts, there was never a hint of Moody personally profiting from these funds. Always careful to spend as little as possible and thereby use more resources for “the work,” funds materialized and able directors helped Moody launch three schools in Northfield. First came the Northfield Seminary for Young Women. Moody’s desire was to provide college preparatory education for lower-economic-class girls in New England, who, on their own, would never be able to get the quality education required to attend a New England college. By autumn 1879 the seminary opened for young women who were given scholarships from funds provided by philanthropists. At the Northfield Seminary, young women studied liberal arts and sciences from a decidedly Christian worldview that was enriched by classes in Bible, church history, and theology.

The Northfield School produced so many able young women—most of whom headed to college and the mission field—that the vision expanded to offer a similar school for young men. In the early 1880s, Mount Herman opened its doors for boys, and the dormitory and classes were filled with socially and economically disadvantaged young men.

The Northfield School produced so many able young women—most of whom headed to college and the mission field—that the vision expanded to offer a similar school for young men. In the early 1880s, Mount Herman opened its doors for boys, and the dormitory and classes were filled with socially and economically disadvantaged young men.

What became a remarkable distinctive of both the Boys’ School and Northfield women’s seminary were their racial diversity. Black, brown, and yellow-skinned men and women attended these schools, and Christian speakers and preachers—black, white, and Asian—ascended the pulpits and podiums of both schools. Such diversity was unknown in most schools in the United States at that time.

To complement the Chicago Bible School and the two preparatory seminaries in Northfield, Mr. Moody felt constrained to launch one more school. During his preaching tours all over New England and the northeast in the late 1870s and 1880s, Moody discovered a class of women he wanted to help. Typically they were rural women with little or no formal schooling. They had committed their lives to Christ and his kingdom at one of Moody’s meetings and soon thereafter felt called to foreign or home missions. To be sure there was a growing demand for women to serve in foreign missions, and there was a pressing need for women to minister in America’s growing cities. Countless urban churches were calling for women to do evangelism and house-to-house personal work among the urban poor. Moody wanted to connect the women called to serve with the cities needing workers.

The Northfield Seminary was no option for these women, many of whom were barely literate; furthermore, because they were already in their twenties, thirties, or forties, they would never have meshed with the Northfield Seminary culture. The Chicago Bible Institute was certainly an option, but it only had room for 250—and it was [always] full. Also, it was a thousand miles away from most of the women seeking help.

Moody often prayed and said, “Lord Jesus I wish I could look into your face and ask you what I should do. Please help me equip these folks you have selected as ‘chosen vessels.’” Invariably the faithful evangelist and disciple maker would get a nudge or an illumination. This time he felt led to go to the manager of “The Northfield,” a hotel where well-to-do Christians went for summer holidays and Bible conferences. “The Northfield” remained vacant during the tourist off season, from October to March. Moody asked the manager if he could rent the three-story, red-brick structure that was graced on three sides with lounging verandas overlooking large lawns and gardens. The spacious hotel with its well-appointed rooms, complete with large windows, draperies, beds, writing desks, and comfortable furniture, was only used between April and September.

The manager of “The Northfield” knew Mr. Moody well. Likewise he shared the preacher’s desire to see disciples trained who could reach unchurched people. Soon an arrangement was finalized, and in October 1890 fifty-six women from eleven states and seven Christian denominations arrived for six months of in-depth training in English Bible, Christian doctrine, and practical theology, as well as music, nursing, cooking, sewing, and hygiene. By the time of Mr. Moody’s death in 1899, more than seven hundred women had completed one to four terms at the Northfield Bible Training School, a Bible and vocational institution. There they were prepared to do personal work that included teaching Scripture to adults and children. They also learned to pray, make clothes for the needy, and prepare food for the sick. Quite astonishingly, this was done without purchasing a building or establishing an endowment. Instead, people of means were asked to help underwrite the hundred dollars per term that the students were charged, because few, if any, had the means to fully pay their own way.

Books and Conferences

Dwight Moody also adopted less formal means to equip people. Early on in ministry, Moody saw the need for Christian books and magazines. To that end he managed to get his brother-in-law, Fleming H. Revell, to launch what became a highly successful publishing house where books by men such as A. J. Gordon, F. B. Meyer, R. A. Torrey, A. T. Pierson, D. W. Whittle, and Moody himself were published and circulated throughout the English-speaking world.

When Fleming Revell refused to risk expanding his publishing company into the untried field of inexpensive paperback books, Moody began his own publishing company, the Bible Institute Colportage Association. This venture produced hundreds of new titles that could be inexpensively printed and distributed to prisons, jails, schools, and churches and eventually became Chicago’s famous Moody Publishing and Moody Press.

Besides printing inexpensive books as methods for evangelism and disciple making, Mr. Moody became an early advocate of summer conferences. Utilizing the hills and rocky fields surrounding his boyhood home and the Northfield and Mount Hermon Schools, Moody sponsored week-long summer Bible and deeper-life conferences where some of the world’s best Bible teachers and preachers were brought to teach and inspire laymen and women.

Finally, D. L. Moody, who always had a burden to train young people for “the work,” sponsored summer conferences for college students. His first such meeting was held on the Mount Hermon Boys’ School campus from July 7 to 31, 1886. More than 240 students traveled by train and foot, lived in tents or in the open air, to be mentored by authors, missionaries, and preachers whom God would use to call them to home and foreign ministry. Soon students from as far away as the United Kingdom, Japan, German, Norway, and Siam descended upon northwestern Massachusetts—making tiny Northfield a place of international significance.

Conclusion

Few people have done more than Dwight L. Moody to evangelize lost souls and mentor and train the next generation to fulfill the Great Commission. What explains his extraordinary success? First of all, from the moment he heard the British evangelist Henry Varley say, “It remains to be seen what the Lord can do with a man wholly consecrated to Christ,” the idea captivated him.

Few people have done more than Dwight L. Moody to evangelize lost souls and mentor and train the next generation to fulfill the Great Commission. What explains his extraordinary success? First of all, from the moment he heard the British evangelist Henry Varley say, “It remains to be seen what the Lord can do with a man wholly consecrated to Christ,” the idea captivated him.

He determined to be such a man. Moody was a “chosen vessel,” to be sure. But he gradually became a man with a single eye. Few men or women in modern times have been as determined as Dwight L. Moody to experience the truth of 2 Chronicles 16:9: “For the eyes of the Lord range throughout the whole earth, to strengthen those whose hearts are fully committed to him.”

Every person who knew Moody well observed his love for Jesus Christ, his passion for souls, and commitment to do what he believed the Lord called him to do. To his friend D. W. Whittle he wrote, “I have done one thing, and the work is wonderful. One thing is my motto.” His son Will said, “Nothing could sever him from this deep-rooted purpose of his life, and in all the various educational and publishing projects to which he gave his energy. . . . There was but one motive—the proclamation of the Gospel through multiplied agencies.”

Lyle Dorsett

Professor, Senior Fellow for Spiritual Formation, CSLILyle Dorsett, Professor, holds the Billy Graham Chair of Evangelism at Beeson Divinity School in Samford University. He taught courses in evangelism, spiritual formation and church history. He also serves as the pastor of Christ the King Anglican Church in Homewood, Alabama. Lyle received his PhD in American history and has published numerous books, including several Christian biographies and three works on C. S. Lewis.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

A Welcome Change in Apologetics

by Randy Newman, Aimee Riegert on April 19, 2024We’re burdened for our friends who don’t know...Read More

-

Questions That Matter Podcast – Samuel James and Digital Liturgies

by Samuel James, Randy Newman on April 19, 2024

-

The Side B Stories – Dr. James Tour’s story

by Jana Harmon, James Tour on April 12, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Isn’t Morality Relative?

by Christopher L. Reese on April 1, 2024It is widely accepted in the Western world...Read More

-

Do Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God?

by Andy Bannister on March 1, 2024

-

Artificial Intelligence and Its Impacts on Humanity

by John Lennox on February 13, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

22140

GLOBAL EVENT: Keeping the Faith From One Generation To Another with Stuart McAllister and Cameron McAllister, 8:00PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=global-event-keeping-the-faith-from-one-generation-to-another-with-stuart-mcallister-and-cameron-mcallister-800pm-et&event_date=2024-05-17®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-05-17

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

GLOBAL EVENT: Keeping the Faith From One Generation To Another with Stuart McAllister and Cameron McAllister, 8:00PM ET

On May 17, 2024 at 8:00 pmSpeakers

Lyle Dorsett

Professor, Senior Fellow for Spiritual Formation, CSLI

Team Members

Lyle Dorsett

Professor, Senior Fellow for Spiritual Formation, CSLILyle Dorsett, Professor, holds the Billy Graham Chair of Evangelism at Beeson Divinity School in Samford University. He taught courses in evangelism, spiritual formation and church history. He also serves as the pastor of Christ the King Anglican Church in Homewood, Alabama. Lyle received his PhD in American history and has published numerous books, including several Christian biographies and three works on C. S. Lewis.