Back to series

The Story That Makes Sense of All Stories

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

The great churchman and theologian, Lesslie Newbigin, came back into the West after 40 years in India where he had seen his vocation as translating the gospel of the kingdom into Hindu culture. Upon his return to England, he wondered at the working assumption that marked the church’s engagement of contemporary culture. It seemed clear to him that the West was post-Christian, becoming pagan, and he could not understand why the church continued to relate to the world as if Christendom was still a reality.

And so he began to write, addressing the church at the end of the 20th-century, asking “Does it still make sense to speak about the gospel as true, even in a pluralist society?” In Foolishness to the Greeks, Beyond 1984, Proper Confidence, Truth to Tell, and one titled, very plainly, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society, he took up the task of arguing for the truth of the gospel in an evermore secularizing, pluralizing world. Taking on the hardest questions, the most complex issues, his critique is incisive, and his vision of a way forward marked by unusual wisdom and grace.

He tells of a conversation with a Hindu scholar, in which they talked about the possibility of a story that could make sense of all stories. “A learned Hindu friend has several times complained to me that we Christians have misrepresented the Bible. He has said to me something like this:

As I read the Bible I find in it a quite unique interpretation of universal history and, therefore, a

unique understanding of the human person as a responsible actor in history. You Christian missionaries

have talked of the Bible as if it were simply another book of religion. We have plenty of these already in India and

we do not need another to add to our supply.1

At one point late in his life I asked Newbigin about this man, and he told me that the Hindu was a long-time friend, the kind that one could not see for years, but when reunited, enter again into the most important conversations. We all hope for friends like that.

What impressed me about the conversation is that the Hindu saw more clearly than do many Christians. What is the Bible anyway? The Christian’s holy book? Our parochial perspective on life and the world? No, no, a thousand times no. The Bible is not just one more book of religion to add to anyone’s supply. It is the Story that makes sense of all stories, and the Hindu could see that that was both its claim and its promise. The vision of history and human nature which are integrally woven into the worldview of its text are central to our deepest yearnings as sons of Adam and daughters of Eve. We long for meaning and purpose, for accountability and responsibility, and the Hindu could see that the Christian holy book was unique among holy books in its ability to offer such hope.

What impressed me about the conversation is that the Hindu saw more clearly than do many Christians. What is the Bible anyway? The Christian’s holy book? Our parochial perspective on life and the world? No, no, a thousand times no. The Bible is not just one more book of religion to add to anyone’s supply. It is the Story that makes sense of all stories, and the Hindu could see that that was both its claim and its promise. The vision of history and human nature which are integrally woven into the worldview of its text are central to our deepest yearnings as sons of Adam and daughters of Eve. We long for meaning and purpose, for accountability and responsibility, and the Hindu could see that the Christian holy book was unique among holy books in its ability to offer such hope.

It is this Story with which we begin, as we seek to orient ourselves to understanding the arts as one expression of human responsibility in history. It seems almost too simple to say that the story that Scripture tells begins at the beginning. Yet it does, and it is profound in the way that it shapes human life under the sun, from the first days on into our own.

Creation, Fall, Redemption, Consummation

“In the beginning God made….” Yes, yes, and yes again. God imagined a universe, and set it into motion. Sun, moon, stars, galaxies, seas, mountains, birds, bears, beavers, and finally the crown of his creation, a man and a woman, given the task to understand and develop the world, to care for it in God’s name. Some translations offer the word “dominion” as a way of getting at the complex character of the task given to Father Adam and Mother Eve. Just as God is the sovereign of all that he has made, he gave the first man and the first woman a sovereignty-of-sorts, a dominion, over all that he had made; in effect saying to them, “I give you responsibility. Be creative in my creation, and understand what I have made. Enjoy it and use it well. Develop its possibilities. Love it as I love it.”

Though the Fall radically affected that charge, skewing the human heart and every aspect of the creation, dramatically distorting the purposes God had intended for his stewards and their task, the mandate remains. God’s word to his world is sure and sustained—even in a horribly sin-shaped existence. It is with toil and pain that the work of stewardship is now done, but the work is still to be done. Land is to be tilled, tools are to be made, music is to be made, children are to be born, cities are to be built—the task of forming culture is still written into the human heart.

But with such toil and pain we take up that task. Will it ever change? Can it ever be different? As the tale is told in the Old Testament, from Genesis 3 onward, there is the promise of a day of salvation, a day when all will be made right, viz. someday the seed of the woman will crush the head of the serpent. We have windows into this generation after generation, as God unfolds his purposes, in love choosing to redeem a people and their world.

One of the most fascinating moments along the way is the story of God’s chosen people in exodus, on their way out of Egypt and on their way to the land of promise. With great drama, God stops them in their tracks, and speaks to them from a mountain, giving “ten words” which will be life to them—should they choose to hear with their hearts. He also gives them extensive instruction about the way they are to worship and work, live and learn. As he explains the whys and wherefores, the what and the hosws, he then says:

The LORD spoke to Moses and said, Mark this: I have specially chosen Bezalel son of Uri, son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah. I have filled him with the Spirit of God, making him skillful and ingenious, expert in every craft and a master of design, whether in gold, silver, copper, or cutting stones to be set, for carving wood, for workmanship of every kind. FurtherI have appointed Oholiab son of Ahisamach of the tribe of Dan to help him, and I have endowed every skilled craftsman with the skill which he has.

Exodus 31:1-6

If ever we needed a biblical account of the vocation of artist, here it is! God has called, and God has gifted through his Spirit particular people to be artists—for the glory of God and for the sake of beauty in his world, even a world marred by sin with all of its distortions, all of its sadnesses, all of its pains.

It is not an isolated example. The God who creates sunsets and seas, butterflies and elephants, Rocky Mountain peaks and Midwest prairies, pink dogwood blossoms and bright red roses, in each generation calls out certain persons to creative acts that serve him and his world. Haven’t you ever wondered about the shepherd-become-king David, and his tune “The Lilies of the Covenant”? In the Psalms, themselves songs of wide-ranging emotion, the instruction is to sing particular songs to particular tunes, such as “The Lilies of the Covenant.” Simply said, it sounds beautiful. (I can’t wait to hear it…. walking around a corner in the New Jerusalem and finding to my deepest pleasure David with Bach and Bono jamming, working off of each other’s God-graced gifts to the age-old tune, “The Lillies of the Covenant”!)

This unfolding of God’s work through his people Israel—through prophets, priests, and kings, poets, craftsman, and designers, each in their own way wondering and hoping, making choices that blessed and cursed their generations and ones that followed –it all points towards the long-awaited day of salvation, the renewal of all things in the cross and resurrection of Christ. The angels of heaven sing gloriously of “Peace on earth,” and each and every one of us longs for the reality of redemption—in every area and arena of human life, from the most personal to the most public.

This unfolding of God’s work through his people Israel—through prophets, priests, and kings, poets, craftsman, and designers, each in their own way wondering and hoping, making choices that blessed and cursed their generations and ones that followed –it all points towards the long-awaited day of salvation, the renewal of all things in the cross and resurrection of Christ. The angels of heaven sing gloriously of “Peace on earth,” and each and every one of us longs for the reality of redemption—in every area and arena of human life, from the most personal to the most public.

We yearn for the dissonance in our souls to be over, for the struggles in our families to be finished, for the work of our hands to deeply satisfy and serve, for our relations with neighbors near and far to be what they ought to be—if in fact Jesus is Lord and he is bringing “peace on earth” not just for some future day, but for now. That is the substance of our hope.

The renewal of all things means all things. As Hebrews 2 argues, someday we will see it all: everything made new, because everyone will understand that Jesus is Lord of Lords and King of Kings. But for right now, we are in what some have called “the now but the not yet” time in history; when peace has been made through the death and resurrection of Christ, but we do not yet see all of its fruits—only its first fruits. Someday, someday, it will be the whole shebang, a cosmic redemption! Everyone and everything made new.

But for now, as we worship and work and wait, the mandate given at the very beginning is still in place: “I give you responsibility. Be creative in my creation, and understand what I have made. Enjoy it and use it well. Develop its possibilities. Love it as I love it.” In every way our responsibilities are more complex, full of both frustrations because of the Fall, but also because history has brought into being so many more possibilities. A garden has become a city… and another city and another city, until the whole earth seems full of cities. A man and a woman

have become billions of men and women, scattered all over the face of the earth. And on and on.

But the mandate remains. From creation, through the fall, on into redemption, the call to care for God’s world in his name, to take up responsible dominion in the forming of cities and families, of societies and cultures, is still there, shaping human life under the sun. And God is still giving gifts, through his Spirit, so that his own creativity, his own imaginative heart and mind might be expressed in the creative gifts of his people. Never an end in themselves, but always an evidence of the possibilities built into the creation itself, waiting to be discovered—for a new generation to enjoy and use.

And of course each generation has the charge of remembering to remember that the gifts have a giver, that creativity itself is a possibility only because we are made in the image of the Creator.

For centuries and centuries, Christian people have seen the world through the spectacles of this story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation. Augustine of Hippo was deeply grounded in this vision, in many different places reflecting upon the world in light of this motif for moral meaning. One of his best contributions comes in the way that he articulated the nature and character of responsibility, arguing:

At creation, Adam and Eve were posse peccare, posse non peccare

At the fall, they were non posse, non peccare

At redemption, they were posse non peccare

And at the consummation, they were non posse peccare

We do not have to be Latin scholars to understand the Augustinian vision. At each moment in the biblical story our place in the moral universe is different: able to sin, able not to sin (creation); not able not to sin (fall); able not to sin (redemption); and not able to sin (consummation).

Making sense of sin, of our responsibility, of our choices and their consequences, is complex and perplexing. Fifteen hundred years later it is a good gift to us to have Augustine’s paradigm to ponder, as it still rings true for those whose lives are shaped by Scripture and the story it tells.

The Hindu scholar was right, profoundly. The Story told in Scripture is not “one more to add to our supply”—rather it is a way of seeing all of life, all of history, each of our lives with each of our histories, in a way that makes sense of our hopes and dreams, our gifts and skills—even the dimension of human activity we call the arts. In a pluralist society, that is the gospel, that is good news.

1 Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), p. 89.

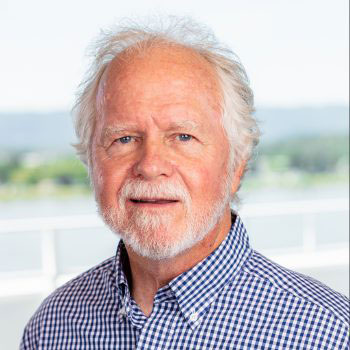

Steven Garber

ProfessorSteven Garber is the Senior Fellow for Vocation and the Common Good for the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust. As a teacher, he has recently served as Professor of Marketplace Theology and Director of the Masters in Leadership, Theology and Society at Regent College, Vancouver, BC. he is the author of several books, including Visions of Vocation: Common Grace for the Common Good, his most recent is The Seamless Life: A Tapestry of Love and Learning, Worship and Work. One of the founders of the Wedgwood Circle, and has been a Principal of the Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation and Culture. He completed his PhD in the Philosophy of Learning at Pennsylvania State University.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

A Welcome Change in Apologetics

by Randy Newman, Aimee Riegert on April 19, 2024We’re burdened for our friends who don’t know...Read More

-

Questions That Matter Podcast – Samuel James and Digital Liturgies

by Samuel James, Randy Newman on April 19, 2024

-

The Side B Stories – Dr. James Tour’s story

by Jana Harmon, James Tour on April 12, 2024

-

Recent Publications

Isn’t Morality Relative?

by Christopher L. Reese on April 1, 2024It is widely accepted in the Western world...Read More

-

Do Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God?

by Andy Bannister on March 1, 2024

-

Artificial Intelligence and Its Impacts on Humanity

by John Lennox on February 13, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

22140

GLOBAL EVENT: Keeping the Faith From One Generation To Another with Stuart McAllister and Cameron McAllister, 8:00PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=global-event-keeping-the-faith-from-one-generation-to-another-with-stuart-mcallister-and-cameron-mcallister-800pm-et&event_date=2024-05-17®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2024-05-17

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

GLOBAL EVENT: Keeping the Faith From One Generation To Another with Stuart McAllister and Cameron McAllister, 8:00PM ET

On May 17, 2024 at 8:00 pmTags

Speakers

Steven Garber

Professor

Team Members

Steven Garber

ProfessorSteven Garber is the Senior Fellow for Vocation and the Common Good for the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust. As a teacher, he has recently served as Professor of Marketplace Theology and Director of the Masters in Leadership, Theology and Society at Regent College, Vancouver, BC. he is the author of several books, including Visions of Vocation: Common Grace for the Common Good, his most recent is The Seamless Life: A Tapestry of Love and Learning, Worship and Work. One of the founders of the Wedgwood Circle, and has been a Principal of the Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation and Culture. He completed his PhD in the Philosophy of Learning at Pennsylvania State University.